STRANGER TO HISTORY

A Sons Journey through Islamic Lands

Aatish Taseer

Graywolf Press

Copyright 2009, 2012 by Aatish Taseer

First published by Canongate Books, Edinburgh

Some material in 2011: Deaths New Context has appeared previously, in different form, in the Wall Street Journal and the Sunday Telegraph.

This publication is made possible in part by a grant provided by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature from the Minnesota general fund and its arts and cultural heritage fund with money from the vote of the people of Minnesota on November 4, 2008, and a grant from the Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota. Significant support has also been provided by the National Endowment for the Arts; Target; the McKnight Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-55597-628-6

Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-063-5

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2012

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012936228

Cover design: Kimberly Glyder Design

Cover photo: Corbis

For Ma

2011: Deaths New Context

MALCOLM. Nothing in his life

Became him like the leaving it; he died

As one that had been studied in his death

To throw away the dearest thing he owed,

As twere a careless trifle.

Macbeth, Act I, Scene IV

A ll books have a text and a context. There is an invariable gap between the two which widens with time; it is usually a gradual process. In the case of this book, that gap has widened so dramatically in the three years since it was first published that it has made the writing of these pages essential. It is safe to say: no book, so soon after its original publication, has needed a new introduction as badly as this one.

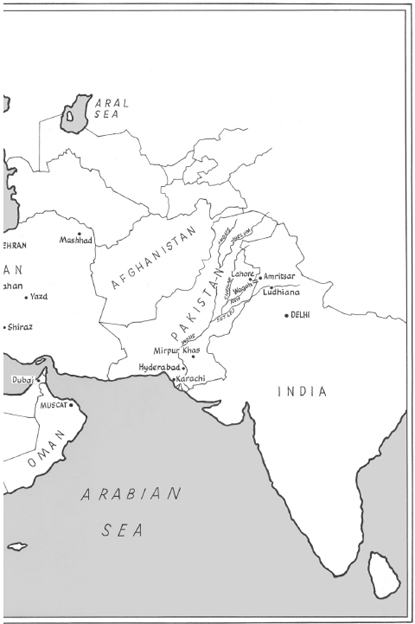

When I first began writing Stranger to History my father had been out of politics for nearly fifteen years. He was a businessman in Lahore; and, for the purposes of this book, which was written in part to tell the story of my complicated relationship with him, he neednt have been anything else. But and such has been the life of this book and its subject by the time the first draft was ready, my father had reentered politics as a caretaker minister in General Musharrafs government. A few months later, just before publication, he was appointed governor of Punjab, Pakistans most populous province; two years later, on a cold January afternoon in 2011, he was dead, assassinated in Islamabad by a member of his own security detail.

The man who killed my father killed him for defending a Christian woman accused of blasphemy and for opposing the laws that had condemned her. For this, he became a hero in Pakistan, a defender of the faith, and my father in the eyes of many was declared wajib ul-qatl, the Islamic designation given to a man fit to die, a transgressor against the faith whom any good Muslim might kill. The trial that followed was less a murder trial my fathers killer had laid down his gun and confessed his crime than it was a trial about my fathers faith; and, whether his killer had been justified under extreme provocation to act against a transgressor. The defense, in building their case against my father, sought to rubbish his credentials as a Muslim, moving easily towards the conclusion that if he had not been Muslim in the way they wanted him to be, he deserved to die.

In this ugly reconfiguration of reality, Stranger to History, which had been one thing in one time, became another thing in another time. It was used in court to condemn my father, making the case that he was not a practicing Muslim; that he drank alcohol; that he ate pork; that he in another life some thirty years before had fathered a half-Indian child by an Indian woman.

*

Stranger to History was written as the expression of a need, the need to face and record a suppressed personal history. That history began with my parents meeting in Delhi in 1980. Or even earlier, perhaps, for what was that meeting between a Pakistani politician and the Indian reporter who had been sent to interview him without its context in the 1947 Partition of India! The arrival of my mothers family as refugees in Delhi; the painful shadow of the Partition on my maternal grandfather, an army man who never recovered from the absurdity of fighting wars against men he considered to be his ownthat history, unrecorded once, is there now, in these pages.

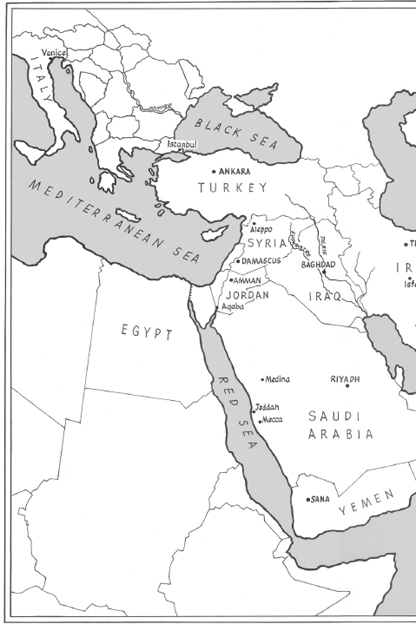

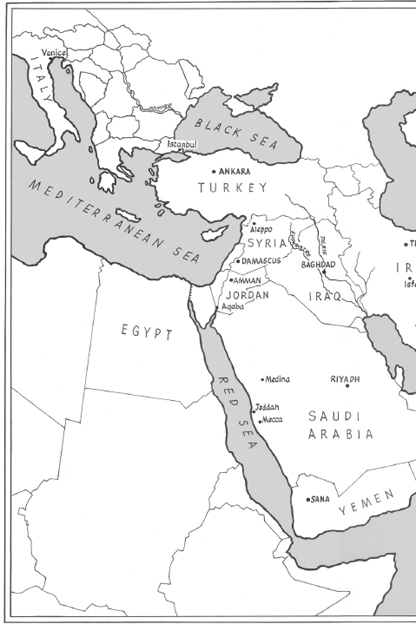

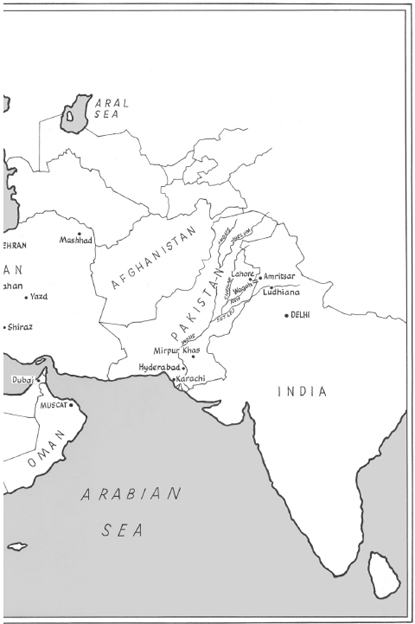

So, too, is the story of my parents love affair and their separation: my fathers return to Lahore to fight General Zias dictatorship, my mothers to Delhi where she raised me. In 2002, at the age of twenty-one, I made a journey to Lahore to seek out my father for the first time. We were reunited; a brief happy period followed, which, in turn, was followed by more rupture and a new silence. We met for the last time on December 27, 2007, the night Benazir Bhutto was killed. That personal history, painful as it can be at times, is also there in this book, interwoven with the account of the larger journey I made in 2005 from Istanbul to Lahore to understand the faith that had made my father and his country.

*

There is no need to go over it again here. What I would like to do instead is to take the story forward to the time after Stranger to History.

The book ends with Benazir Bhuttos assassination and my final meeting with my father. I am grateful for that meeting; it gave me an insight into a man I had not always been able to judge kindly.

I wrote at the time:

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had, in a way, also died from a wound to the neck. That had been the beginning of my fathers political fight. The person we watched taken away in a simple coffin, now with no fight left in her, was his leader when that career came to fruition. It could be said that all my fathers idealism his jail time, the small success and the great disappointment, the years when he struggled for democracy in his country were flanked by this father and daughter who both died of fatal wounds to the neck. And running parallel to these futile threads, with which my father could string his life together, were the generals, one whom he had fought and the other in whose cabinet he was now a minister.

For it to be possible for men to live with such disconnect, for my father to live so many lives, the past had to be swept away each time. The original break with history that Pakistan made to realise the impulses of the faith, and which gave it the rootlessness it knew today, had to be repeated. Like the year of events, which had ended in trauma, all that could be wished for was the distraction of the next event. But in these small interims when the past could be seen as a whole, when my father could cast painful bridges over history, I felt a great sympathy as I watched the man I had judged so harshly, for not facing his past when it came to me, muse on the pain of history in his country. And maybe this was all that the gods had wished me to see, the grimace on my fathers face, and for us, both in our own ways strangers to history, to be together on the night that Benazir Bhutto was killed.