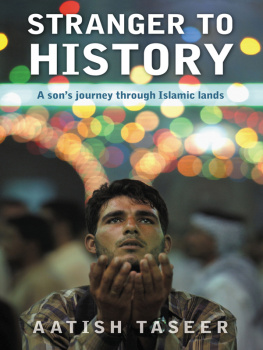

Aatish Taseer was born in 1980 and has worked

as a reporter for Time magazine. He lives between

London and Delhi. This is his first book.

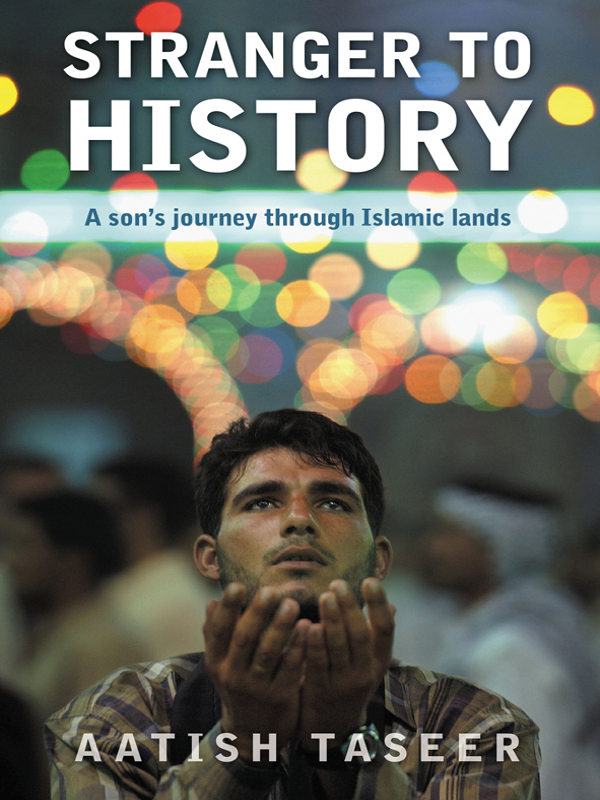

STRANGER TO

HISTORY

A sons journey through Islamic lands

AATISH TASEER

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William St

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright Aatish Taseer 2009

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Canongate Books, London, 2009

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company, 2009

Printed and bound by Griffin Press

Cover design by Susan Miller

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Taseer, Aatish.

Stranger to history: a sons journey through Islamic lands/Aatish Taseer.

ISBN: 9781921520174 (pbk.)

Taseer, AatishTravelIslamic countries.

IslamAsia. MuslimsAttitudes.

297.57

For Ma

Contents

Syria International: Notes from the

Translation Room

The Discplinary (sic) Force of the

Islamic Republic

O nce the car had driven away, and we were half-naked specks on the marble plaza, Hani said, Ill read and you repeat after me. His dark, strong face concentrated on the page and the Arabic words flowed out.

Kareem, pale with light eyes, and handsome, also muttered the words. We stood close to each other in our pilgrims clothes two white towels, one round the waist, the other across the torso, leaving the right shoulder bare.

I seek refuge in Allah the Great, in His Honourable Face and His Ancient Authority from the accursed Satan. Allah, open for me the doors of Your Mercy.

It was a clear, mild night and we were standing outside the Grand Mosque in Mecca. The plaza was vast, open and powerfully floodlit. The pilgrims were piebald dots, gliding across its marble surface. The congested city, the Mecca of hotels and dormitories, lay behind us.

The mosques slim-pillared entrance, with frilled arches and two great minarets, lay ahead. It was made of an ashen stone with streaks of white; its balustrades, its minarets and its lights were white. A layer of white light hung over the entire complex. Towers, some unfinished with overhanging cranes, vanished into an inky night sky.

We paused, taking in the plazas scale.

I was mid-point in a much longer journey. I had set out six months earlier in the hope of understanding my deep estrangement from my father: what had seemed personal at first had since shown itself to contain deeper religious and historical currents. And it was to discover their meaning that I travelled from Istanbul, on one edge of the Islamic world, through Syria, to Mecca at the centre and the Grand Mosque itself. The remaining half of my journey was to take me through Iran and, finally, into Pakistan, my fathers country.

We walked on like tiny figures in an architects drawing towards the mosque. The plazas white dazzle and my awe at its scale had made me lose the prayers thread. Hani now repeated it for me slowly, and I returned the unfamiliar words one by one. My two Saudi companions, experienced in the rituals we were to perform, took seriously their role as guides. They seemed to become solemn and protective as we neared the mosques entrance. Hani took charge, briefing me on the rites and leading the way. Kareem would sometimes further clarify the meaning of an Arabic word, sometimes slip in a joke. Now, no flat-screen TVs and electronics, he warned, of the prayer we would say inside the sanctum.

We were channelled into a steady stream near the entrance. The pilgrims, who had been sparse on the plaza, gathered close together as we entered. The women were not in the seamless clothes required of the men, but fully covered in white and black robes. Inside, the mosque felt like a stadium. There were metal detectors, signs in foreign languages, others with letters and numbers on them. Large, low lanterns hung from the ceilings, casting a bright, artificial light over the passage. On our left and right, there were row after row of colonnades, a warren of wraparound prayer galleries. The mosque was not filled to even a fraction of its capacity, and its scale and emptiness made it feel deserted. Then, Hani whispered to me the prayer that was to be said around the Kaba. The Kaba! I had forgotten about it. It hovered now, black and cuboid, at the end of the passage. And once again, confronted with an arresting vision, Hanis whispered prayer was lost on me.

The Kabas black stone was concave, set in what looked like a silver casque, and embedded in one corner of the building. It had been given by the angel Gabriel to Ishmael, the progenitor of the Arab race, when he was building the Kaba with his father, Abraham. Many queued to touch it and kiss its smooth dark surface. We saluted it and began the first of seven circumambulations. Hani read as we walked and I repeated after him. After every cycle, we saluted the stone, and said, God is Great.

The pilgrims immediately in front of us were three young men in a mild ecstasy. They had their arms round each other and skipped through their circuits. The language they spoke gave them away as south Indians. They overlapped us many times and their joy at being in Mecca was infectious. Behind us, a man who seemed Pakistani moved at a much slower pace, pushing his old mother in a wheelchair round the Kaba. She was frail and listless, her eyes vacant: she had saved their fading light for the sacred house in Mecca. Then another overlapper hurried past in an effeminate manner, flashed us a bitter smile, and hastened on.

The vast array of humanity at the mosque, their long journeys encoded in the languages they spoke and the races they represented, brought a domiciliary aspect to the mosques courtyard. People napped, sat in groups with their families, prayed and read the Book. The hour was late, but no one seemed to notice; this, after all, was the destination of destinations.

When we had circled the Kaba seven times, we moved out of the path of orbiting pilgrims and prayed together. Behind the double-storey colonnades and their many domes, there were brightly lit minarets and skyscrapers. I felt as if I was in a park in the middle of a heaving modern city.

We had rushed things. We sat next to each other, a little sweaty now, at one end of the courtyard. Kareem, prolonging the prayer, sat on his shins. His handsome face, normally bright with an ironic smile, was quiet and closed. Hanis eyes were closed too, his dark lips moving silently. A moment later we rose for the last rite: Hagars search for water.

There are many versions of the story, but the key facts are that Hagar, Abrahams wife, is stranded with the infant Ishmael in the vicinity of Mecca. She runs seven times between Mounts Safa and Marwa until an angel appears to her. He stamps on the ground and water springs up where the ZamZam well is to quench the thirst of mother and child. It was Hagars steps, her fear and deliverance, a sign of God watching over Muslims, that we were to retrace.

Next page