I have taught world religions at the college level for almost twenty years now. When I began, I did not know that I would be writing a book about it in the future. Although many of my memories remain clear to me, I cannot back them up with transcripts or recordings. Where I have told the stories of others, I have disguised their identities or left them easy to identify, depending on what they asked me to do when they gave me their permission. In some cases I have gathered memories from several different years and put them into the same time frame. In every case I have told the truth to the best of my ability, fully aware of how many tricks memory can play. The best disclaimer I have ever heard is broadcast at the beginning of every Moth Radio Hour, my favorite program on public radio: Moth stories are true as remembered and affirmed by the storyteller. So are mine.

What do they know of England, who only England know?

R UDYARD K IPLING

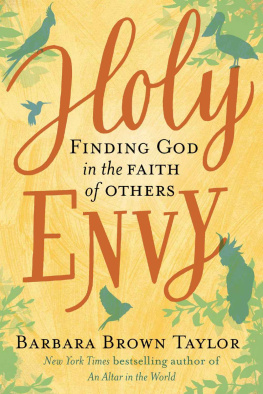

T he book in your hands is a small window on a large subject. Set at a private liberal arts college in the foothills of the Appalachians, it is the story of a Christian minister who lost her way in the church and found a new home in the classroom, where the course she taught most often was not Introduction to the New Testament, Church History, or Christian Theology, but Religions of the World. As soon as she recovered from the shock of meeting God in so many new hats, she fell for every religion she taught. When she taught Judaism, she wanted to be a rabbi. When she taught Buddhism, she wanted to be a monk. It was only when she taught Christianity that the fire sputtered, because her religion looked so different once she saw it lined up with the others. She always promised her students that studying other faiths would not make them lose their own. Then she lost hers, or at least the one she started out with. This is the story of how that happened and what happened next.

It is my story, but it is also the story of a generation of young Americans who are growing up with more religious diversity than their parents or grandparents did and who are still trying to decide whether this is a good thing or a bad thing. The Christians among them can sense the anxiety in their churches, where changing the music and hiring more millennial pastors have not brought the young people back. Will the Christianity they know best survive, or is it dying of old age? Is the Holy Spirit at work in what is going on, or is a more sinister spirit at work?

Some are questioning whether the churches they grew up in have anything to offer them as they make their ways in a culture of many cultures with many views of truth, some of which make a great deal of sense to them. For those who counted on God to protect them from so many choices, it is as if the heavenly Father let go of their hand in a crowd one day and vanished into a sea of divine possibilities. I cannot protect the students in my classes from this any better than I can protect myself. Existential dizziness is one of the side effects of higher education, and it affects teachers too.

I came to the classroom through the back door. Parish ministry was my front-door job, the one I had been doing for fifteen years when the president of a nearby college called and said there was an opening for someone to teach religion. Would I be interested? I said no the first time. My only credentials were a masters degree in divinity, deep immersion in one Christian denomination, and a lifelong curiosity about religion. All three were do-it-myself projects, since my parents had worked hard to protect me from God while I was growing up. When I was fifteen, I found my father sitting cross-legged in the dining room meditating in front of a biofeedback machine. When I told my mother I wanted to be baptized, she told me I would get over it. Both had such a poor opinion of religion that they raised my two younger sisters and me to believe in higher education instead of a higher power. We went to the library every week, not church. We read Shakespeare, not the Bible.

This left me little choice but to rebel by joining every church in driving distance as soon as I got my license. I was Baptist for a while, then Presbyterian. In college I was an evangelical Christian who hung out with Methodist seminarians during the week and ate supper with Catholics on Sunday nights. But casual conversations were not enough. I wanted thick books, smart teachers, hard theological nuts to crack. I became a religion major, finding more of what I was looking for in the classroom than I had ever found in church. When my adviser suggested seminary, I went, with no ambition but to learn as much as I could about the divine mysteries of the universe from anyone willing to teach me more. A divinity school sounded like exactly the right place.

My favorite professor was an Episcopal priest who taught New Testament with nothing but a tiny Greek edition open on the table in front of him. Above the table he was immaculate, dressed in a black clergy shirt with a starched linen collar and a worsted wool jacket that made him look like a duke. Under the table he wore laced-up leather hunting boots with mud on them, as if he had barely made it to class on time after an early morning walk in the woods. He showed up in my dreams. He also taught me a great deal about the New Testament. When he returned my essays, every page was marked with neatly circled numbers that matched his handwritten comments on lined pages at the back.

No one had ever paid such careful attention to my scholarship, so when I sought him out for spiritual guidance, I did exactly what he said: I began attending Mass at the Anglo-Catholic church downtown, where the divine mysteries on display exceeded anything in my prior experience. Though I quickly learned how to genuflect, chant psalms, and cross myself at the name of the Trinity, it took me a full year to work up the nerve to take Communion. I was too afraid I would do something that caused the Communion wafer to combust in my palmreach out with the wrong hand, for instance, or fail to confess a particularly subtle sin. When I finally found the courage to approach the altar rail and nothing terrible happened, I became a confirmed Episcopalian. The combination of fixed prayer and free thought was exactly what I had been looking for. It was the last church I joined, and the one I still call home.

Ordination was out of the question at the time, since the Episcopal church did not admit women to the priesthood until after my graduation from divinity school. Several years later, when things changed, I completed all the requirements for receiving what are still called holy orders. The bishop signed the papers, the date was set, and in due time I knelt before the altar of a beautiful church with gold crosses painted on the red ceiling, holding very still as my soon-to-be-fellow priests gathered around to lay their hands on my head.