Washington, D.C.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the National Geographic Society.

One of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations, the National Geographic Society was founded in 1888 for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge. Fulfilling this mission, the Society educates and inspires millions every day through its magazines, books, television programs, videos, maps and atlases, research grants, the National Geographic Bee, teacher workshops, and innovative classroom materials. The Society is supported through membership dues, charitable gifts, and income from the sale of its educational products. This support is vital to National Geographics mission to increase global understanding and promote conservation of our planet through exploration, research, and education.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463), write to the Society at the above address, or visit the Societys Web site at www.nationalgeographic.com.

CHAPTER ONE

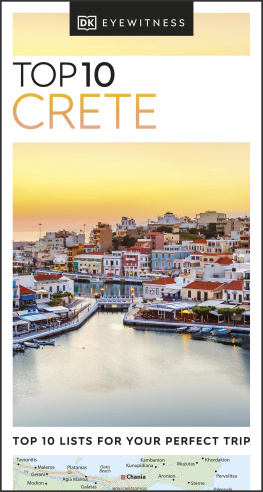

CAVES of ZEUS AND HOUSES of CHRIST

We decided to go in early May. We packed swimming things, but didnt much expect to swim. The sea is too cold at this time of year, for all but the most hardy. A Cretan rarely ventures into the water before July. The sun of May is hot, though, and needs to be treated with respect. My wife, Aira, and I intended to do a lot of walkingCrete is one of the best places for walking that I know ofso sun hats and dark glasses and fairly stout footwear came high on the list of priorities.

The sky looked soft as we came down, but there was nothing soft about the land. One sees the bare bones, boulder-strewn fields with cleared areas, a reddish brown in color, almost terra-cotta, and the distant range of the Lefka Ori, White Mountains, their crests covered with snow. Landing, we were enfolded in the special blend of ancient past and slightly ramshackle present that seems a particular property of the island.

For the Greeks of a later time, Crete was the most venerable and ancient place imaginable. It was where everything began. The first herders of sheep were Cretan, the first beekeepers and honeymakers, the first archers and hunters. These last were the mythical Kouretes, sons of Earth, who attended on the infant Zeus. Since everything began here, it was also the birthplace of Zeus, the father god of the Greeks.

The legend has it that he was born in a cave near the present village of Psychro, high in the Dikte mountains on the southern edge of the Lasithi plateau in eastern Crete. His mother, Rhea, came here to give birth to him in secret, so as to save him from her husband, Kronos, ruler of Heaven, who, having been told that a son of his would supplant him, routinely devoured all his offspring. Rhea presented him with a stone instead, and in his cannibal haste he swallowed it without looking too closely. She then repaired to Crete and had the baby, leaving it in the care of the Kouretes, who in addition to their other achievements were the inventors of the armed dance, clashing their bronze weapons against their shields to drown out the babys cries and so prevent Kronos from discovering the trick that had been played on him and eating this one too.

For the kind of writer I am, stories like this make a strong appeal. I often use the past, sometimes the remote past, as a setting for my fiction. Its a matter of temperament, I suppose, but I find this distant focus liberating, clearing away contemporary clutter and accidental associations that might undermine my story, and allowing me to make comparisons with what I see as the realities of the present. So its a sort of fusion, an interaction of past and present. This is probably one of the reasons why I have always liked Crete, the quintessential land of such fusions.

The exploration of this remote cavern in the mountainside, conducted in the first spring of the twentieth century by D. G. Hogarth, then director of the British School in Athens, had for both of us, when we read about it at home before leaving, all the drama and romance of early archaeology on Crete, carried out by men and women endowed in equal measure with classical learning and a passionate spirit of inquiry. There were no roads, only rough tracks through the mountain passes. The workmen and their equipmentstonehammers, mining bars, charges of gunpowderhad to be transported on mule back. Leonard Cottrell quotes from Hogarths own account in the issue of the Monthly Review, which appeared in the following year. He describes his first sight of the cave, with its abysmal chasm on the left-hand side: The rock at first breaks down sheer, but as the light grows dim, takes an outward slope, and so falls steeply still for two hundred feet into an inky darkness. Having groped thus far, stand and burn a powerful flashlight. An icy pool spreads from your feet about the bases of stalactite columns on into the heart of the hill.

The upper-right-hand chamber had already been broken into and robbed several times over, but the lower, deeper one had never been explored. The blast charges soon cleared away the scattered boulders that had blocked entry to generations of would-be plunderers. The labor force, increased now by the recruitment of female family membersHogarth believed that the presence of women would make the men work betterbegan to dig, descending steeply day by day into the darkness of the cavern until only the dots of light made by their candles could be seen in the distance.

Now comes the miraculous discovery. One of the workers, as he was setting his candle in the narrow crack of a stalactite column, caught sight of a shine of metalthere was a blade wedged there. When drawn out it proved to be a bronze knife of Mycenaean design. There was no way it could have got there by accident: Someone, in the remote past, had brought it as an offering to some god or gods.

Encouraged by this, the party began to search among the crevices of these immeasurably ancient limestone columns that gleamed with moisture in the light of their candles. In the days that followed they found many hundreds of objects: knives, belt clasps, pins, rings, miniature double-headed axes, wedged in slits in the stalactites, brought down by devotees into these awesome depths some four thousand years before. Hogarth had no doubt that he had come upon the original birthplace of Zeus. Among holy caverns of the world, he wrote, that of Psychro, in virtue of its lower halls, must stand alone.