Copyright Christopher Somerville 2007, 2012

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

This edition published in 2012 by

The Armchair Traveller

at the bookHaus

70 Cadogan Place

London SW1X 9AH

www.thearmchairtraveller.com

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ebook ISBN 978 1 907973 33 8

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

info@macguru.org.uk

CONDITIONS OF SALE

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Talking to myself

I n the bus to Sitia, staring out of the dusty windows at the lumpy landscape of eastern Crete, I gave myself a proper talking-to. It was dog trouble once more, revisiting me like an ominous dream bloody big shepherds dogs, three of them, hunting me like wolves up a nameless dirt track. I had beaten off this evil trio many times in the week since my arrival in Crete, but still they rode my waking hours. Other apprehensions slipstreamed behind staggering into a darkened village where every door was locked against me, tumbling headlong down the gorge side, lost on the mountain at nightfall. Yet at the same time raw excitement kept turning my heart over in my stomach.

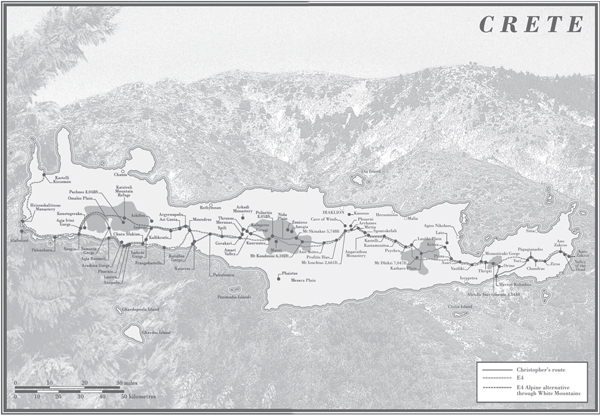

Along with the diesel stink of the bus, this swerving between fear and elation, as if shuttling in an express lift, was making me feel physically sick. I unfolded my two maps of Crete, east and west, across the worn plush seat, and had a steadying look. Already their flimsy coloured paper, printed in Germany, was fraying at the seams. At a scale of 1:100,000 their uselessness to a walker intending to cross the mountainous island from end to end was only too evident. But in this year of 1999 they were the best on offer. They showed the bull-shaped island, familiar to me from many visits over the years, lying between the Cretan and the Libyan Seas. The stumpy hindquarters stretched east to terminate in the little cocked-up tail of the Sideros promontory. The blunt head with its three peninsulas Akrotiri representing the rounded ear of the bull, Rhodopos and Gramvousa the twin horns pushed west. Actually Crete looked less like a bull than a rather scrawny and etiolated rhinoceros. Dotted along its north coast at regular intervals were the chief towns of the island Chania and Rethymnon the elegant Venetian queens of the west, Iraklion (where I had boarded this bus a couple of hours ago) the dusty and noisy capital city in the centre. A little further east lay Hersonissos and Agios Nikolaos, the play-towns of, respectively, more and less downmarket tourism. Out towards the far east the map showed the compact regional centre of Sitia, where the bus driver would be putting me down in an hour or two.

Two other places stood out. I had ringed them round in black ink. Below the Sideros promontory, tucked into a bay at the easternmost end of the island, was the seaside hamlet of Kato Zakros. By the road into the village the cartographer had placed a symbol, a little red classical column. Antique Place, said the key. The 4,000-year-old palace of Zakros lay here, one of the greatest treasures of Cretes Golden Age of Minoan civilisation. At the western tip of the island, about 200 miles away as the crow flew, sat a tiny black square topped by a cross. Moni Hrissoskalitissas was printed alongside in scarlet the Monastery of the Golden Step. Legend said that one step in the flight of 62 that leads up to the monastery was made of gold; but only the pure in heart could see it.

I stared along the map, holding it still against the jolting of the bus. Between the eastern and western extremities of Crete lay four ragged areas where the gentle green of lowland country changed colour to a drab olive brown and the contours ran together in bunches. These were the four mountain ranges that made up the lumpy spine of the bull island Thripti, Dhikti, Psiloritis and Lefka Ori. The latter and more westerly pair were generously overspread with paler patches where the land rose over 7,000 feet above sea level. From previous climbs and dirt road drives I had gathered a very rough impression of these mountains their fierce gorges, their spiny vegetation and rubbly limestone paths, their overhung cliffs and great scrubby slopes falling into shadows; above all, their lonely stretches of mile after rocky mile with no other human in sight. The map breezily ignored these realities. It showed a footpath running from east to west across the whole island, a red wriggling line about 300 miles long, labelled European Hiking Route E4, marching confidently all the way from Kato Zakros to Hrissoskalitissas with never a doubt in its head, hurdling mountains and striding across lowlands with equal nonchalance. Just follow me, it seemed to say. Bobs your uncle. Whats the problem?

No problem except that I had been doing a little checking up online and among personal contacts, and was pretty clear that European Hiking Route E4 was in truth a poorly way-marked, barely visible apology for a path, a fickle companion liable to sneak away and hide when the going got rough in the wild uplands of Crete. It was up in such high and lonely places that my overactive imagination had set all those troubling scenarios of dog attacks and inaccessible crags I had improbably scrambled to. Yet paradoxically it was the mountainous interior of Crete that had called to me from the very first day I had set foot in the island many years before.

The coasts of Crete are famous for their beauty. Each sandy bay looks as if it has been arranged by an exterior designer for the exclusive appreciation of discerning persons. The seas are warm and of an irresistible inshore turquoise that shades out into inky blue. Mountains slope seductively to cliffs and coves. The bathing, sun-worshipping, beer-sipping life never seems more seductive than in the coastal havens of Sougia, of Xerokambos, of Falassarna and Tholos. But my Cretan eyes, somehow, were always lifted to the hills. This must have been largely thanks to George Psychoundakis and his wonderful book The Cretan Runner. Id first devoured this classic account of the Second World War resistance in German-occupied Crete as a teenager, reading my fathers battered old copy. Psychoundakis was a shepherd boy from Asi Gonia in the eastern skirts of Lefka Ori, otherwise known as the White Mountains. In his late teens in 1941 when the Germans invaded and took over his native island, he joined the