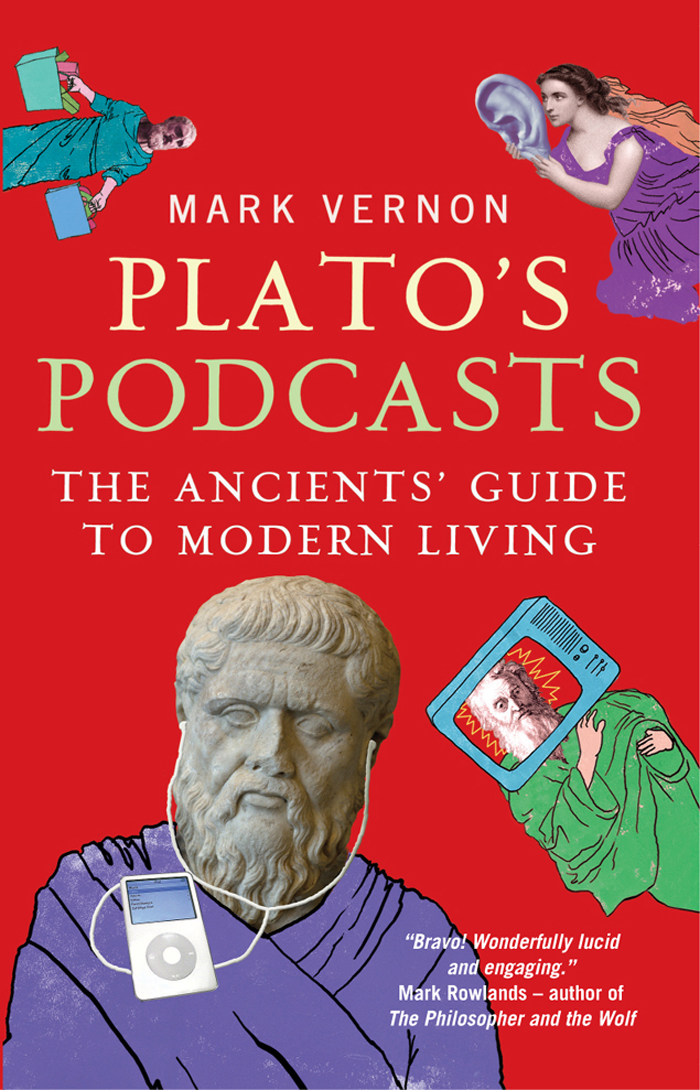

Platos Podcasts

Mark Vernon is a writer, journalist, academic, and former priest. Author of several books, including 42 : Deep Thought on Life, the Universe, and Everything, he is an Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck College, University of London, and a regular contributor to BBC radio and television. He is on the faculty of The School of Life in London.

Platos Podcasts

The Ancients Guide to Modern Living

Mark Vernon

A Oneworld Paperback Original

Published by Oneworld Publications 2009

This ebook edition published in 2013

Copyright Mark Vernon 2009

The right of Mark Vernon to be identified as the

Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 9781851687060

eISBN 9781780744612

Typeset by Jayvee, Trivandrum, India

Cover design by Patrick Knowles

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Road

London WC1B 3SR

England

www.oneworld-publications.com

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

In memory of Paul Fletcher who brought

philosophy to life along with pretty

much everything else.

Contents

Acknowledgements

It is too anachronistic to thank the authors of antiquity upon whom I draw, the eminent, forgotten and curious philosophers themselves, as well as those who recorded their words, notably Diogenes Laertius. However, a number of contemporary scholars of antiquity have proven invaluable too.

I would particularly recommend the scholarly and accessible series Ancient Philosophies published by Acumen. It is superb and fills a gaping hole in the market. John Sellars Stoicism, William Desmonds Cynics, James Warrens Presocratics and Pauliina Remes Neoplatonism have been at my side whilst writing. The indispensable volume for framing the approach Ive taken looking at life as well as thought, seeing ancient philosophy as a practice is laid out by Pierre Hadot in What Is Ancient Philosophy? (Belknap Press), again a clear and penetrating read. Trevor Curnows The Philosophers of the Ancient World: An AZ Guide (Duckworth) is a handy and exhaustive reference: he lists over 2,300 of them. He has also written a short essay, Ancient Philosophy and Everyday Life (Cambridge Scholars Press) that set me thinking. Some useful, short essays can be found in Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didnt know how to ask, edited by Patricia F. OGrady (Ashgate): it is not as frivolous as it sounds. All the translations of ancient Greek and Roman texts are from standard sources. In particular, Diogenes Laertius is taken from R.D. Hicks version of Lives of Eminent Philosophers in the Loeb Classical Library. The other translation particularly to note is that of Sapphos poetry fragments, which are by the poet and classicist Anne Carson.

At Oneworld I would like to thank Mike Harpley very much for commissioning the book; John Sellars, Mike again and an anonymous reader for performing the non-trivial task of commenting on an earlier version of the manuscript. And I recall that the idea stemmed in part from a conversation with Dan Bunyard: thanks again to him too.

Illustrations

The author and publisher have made every effort to ensure copyright. If anything has been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Introduction

There are periods in history when it feels as if almost everything is changing. The economic prosperity that one generation enjoyed is thrown into doubt for the next. There are dramatic shifts in the balance of power, as new political forces appear on the horizon, causing the old consensus to flounder. The daily lives of ordinary people are transformed by sudden progress in the sciences, and are astonishing and unsettling in equal measure. Such moments are commonly regarded warily. They precipitate moral panics, ideological fundamentalism and suspicion amongst neighbours.

They are also times in which some individuals are inspired to dig deep. These rare souls turn again to questions about what it is to be human, what it is to flourish, and out of their enquiries emerge profound insights. They sometimes forge a new philosophy of life that can sustain their fellows for centuries.

Much was up for grabs in the time of Plato and his peers. It is no coincidence that philosophy, the love of wisdom, was born during this turbulent period of history in which one war or another was usually being waged, and in which democracy was established and then fell. The first philosophers who inquired into the nature of things, questioned the gods and encouraged others to think about how they lived, were a ragbag of individuals. They knew they were onto something substantial. But they would never have guessed that, first, their ideas would evolve into traditions of thought and practice that others would follow for a millennium. And then, after the arrival of Christianity, that we would still know them by name and ponder their perceptions to this day.

There is good reason to think that we are living through another era of change. The collapse of the banking system in 2008 will certainly go down as seismic in economic history. By causing uncertainty and challenging consumerism, it has encouraged millions to rethink their lives. And that must be seen in a broader context: the shift in the balance of power from the West to the East; the emergence of a plural society in which every day you might encounter people whose beliefs are different from your own; and the potentially devastating impact of climate change. Now, it can be argued, is a good time to think about what its all about. One way of doing so is to return to roots. So just what was ancient philosophy?

Well, heres one thing to note: Plato wrote dialogues. They portray real characters engaged in the messy business of working out what they believed in life. When you think about it, that was an astonishing thing to do. Youd think a philosopher would want to devise watertight proofs, like an Isaac Newton, not write literature, like a Shakespeare who artfully hides himself in his plays. Nothing could be further from what is called philosophy today. But, so far as we know, Plato did not write a single monograph, treatise or book.

The reason is that a good dialogue invites readers to reconsider what they themselves think. Moreover, it draws them in, so they dont just have to weigh their reasons but their feelings, convictions, character and habits too. Then comes the challenge: are you going to change? For like a play or a novel, a dialogue is not just about the rational content of peoples heads, it can encompass how they live, body and soul. To read a dialogue is, therefore, to be encouraged to muse on how you live too. A dialogue might be said to be like a guide a book of possibilities that presents the choices you might make, and worries over how you might come to terms with them.

Platos dialogues were hugely successful. Writing had been around for some centuries before he, or his secretary, put quill to papyrus in the 390s BCE . But it was only relatively recently that memorised poems had given way to written texts as the preferred means of communicating ideas. The dialogue exploited a new technology. They were read by individuals, and then copied and commended to friends. Like podcasts on the internet today, they spread out like virtual ripples of thought across the ancient Mediterranean world. They left people wanting more. They were provocations to do philosophy, to chew over the innovative, modern ways of life they conveyed.