HOW TO KEEP AN OPEN MIND

ANCIENT WISDOM FOR MODERN READERS

How to Tell a Joke: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Humor by Cicero

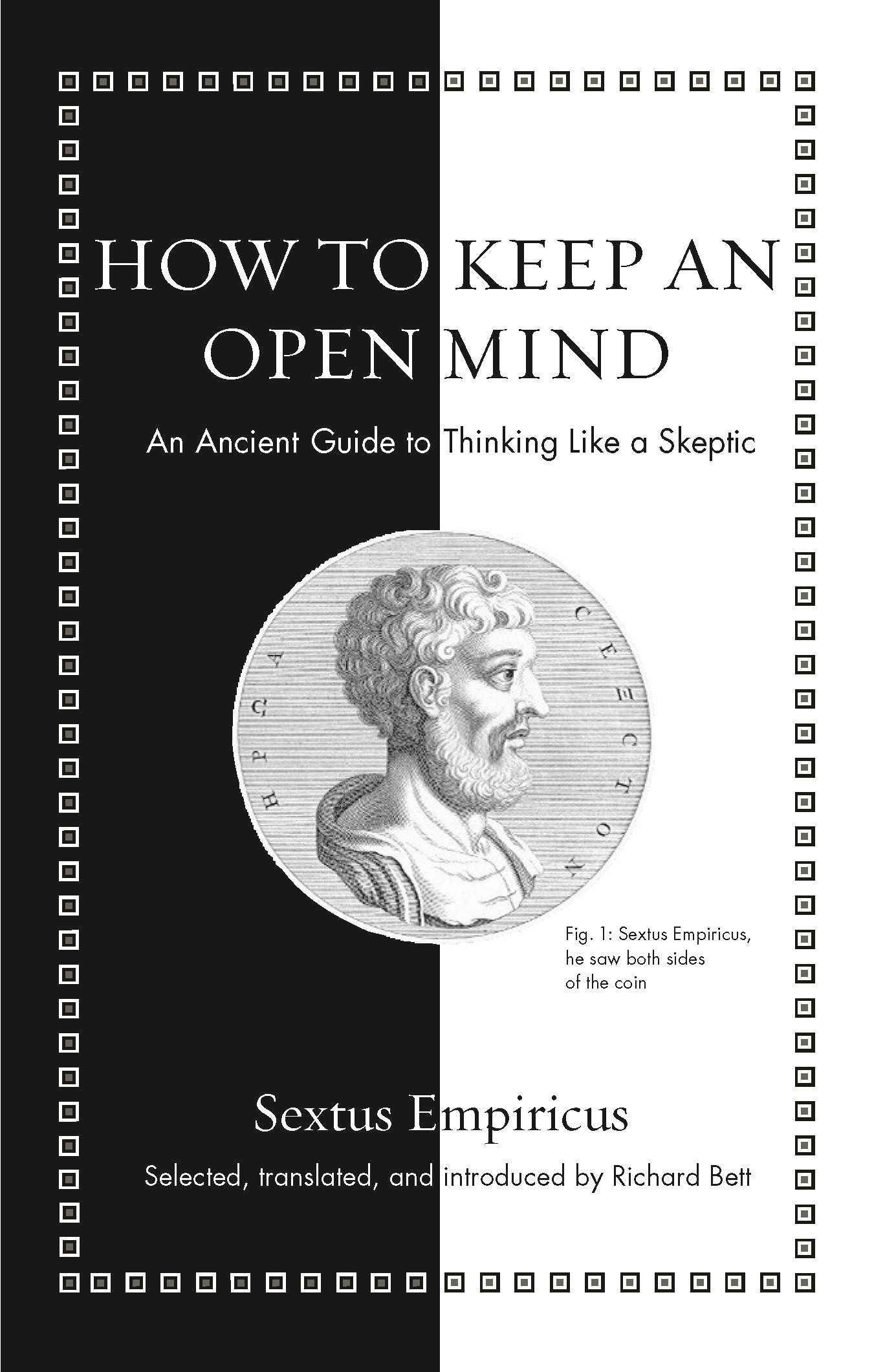

How to Keep an Open Mind: An Ancient Guide to Thinking Like a Skeptic by Sextus Empiricus

How to Be Content: An Ancient Poets Guide for an Age of Excess by Horace

How to Give: An Ancient Guide to Giving and Receiving by Seneca

How to Drink: A Classical Guide to the Art of Imbibing by Vincent Obsopoeus

How to Be a Bad Emperor: An Ancient Guide to Truly Terrible Leaders by Suetonius

How to Be a Leader: An Ancient Guide to Wise Leadership by Plutarch

How to Think about God: An Ancient Guide for Believers and Nonbelievers by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Keep Your Cool: An Ancient Guide to Anger Management by Seneca

How to Think about War: An Ancient Guide to Foreign Policy by Thucydides

How to Be Free: An Ancient Guide to the Stoic Life by Epictetus

How to Be a Friend: An Ancient Guide to True Friendship by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Die: An Ancient Guide to the End of Life by Seneca

How to Win an Argument: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Persuasion by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Grow Old: Ancient Wisdom for the Second Half of Life by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Run a Country: An Ancient Guide for Modern Leaders by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Win an Election: An Ancient Guide for Modern Politicians by Quintus Tullius Cicero

HOW TO KEEP AN OPEN MIND

An Ancient Guide to Thinking Like a Skeptic

Sextus Empiricus

Selected, translated, and introduced by Richard Bett

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number 2021930460

ISBN 978-0-691-20604-2

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-21536-5

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Rob Tempio and Matt Rohal

Production Editorial: Jill Harris

Text Design: Pamela L. Schnitter

Jacket Design: Pamela L. Schnitter

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Jodi Price and Amy Stewart

Copyeditor: Karen Verde

Jacket image: Sextus Empiricus, from a bronze medal, ca. 200250 AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank my home institution, Johns Hopkins University, for a full year of paid sabbatical in 20192020, which allowed me the time to complete this volume (and much else).

I thank Rob Tempio and Matt Rohal, the editor and associate editor for philosophy at Princeton University Press, for getting me interested in doing a volume for the Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers seriesmy first serious venture into what is today usually called public philosophyand for their advice and support along the way.

I thank several friends and relatives outside the academic world who read some or all of the volume in preparation and gave me their impressions: Andrew Bett, Colleen Ringrose, Michael Treadway, and especially Geri Henchy, who read the entire typescript aloud to me as it developed and had many helpful suggestions on how to make things easier to follow.

I thank two people within the academic world whose talks, which I happened to attend while working on this volume, helped me to formulate some of the ideas in the last section of the introduction about what we might be able to learn from Sextus: Michael Walzer (the very distinguished political theorist referred to there) and Jennifer Lackey.

Finally, I thank two anonymous readers for the Press, whose thoughtful comments prompted a number of significant improvements at the last stage of the process, especially in the introduction.

INTRODUCTION

Sextus Empiricus and His Works

A skeptical person, as the term is normally used today, is someone who is inclined to be doubtfulwho doesnt accept what others tell them without a good deal of persuading. The ancient Greek skeptic with whom we will be concerned here, Sextus Empiricus, certainly has something in common with this person, but he is quite a bit more single-minded about it. He has a series of ready-made techniques for making sure that he (or whoever these techniques are applied on) never accepts anythingor at least, anything put forward by someone who claims to understand how the world works. Instead, he suspends judgment about all matters of that kind. And the payoff for this suspension of judgment, he says, is that you are much calmer and less troubled than other people; skepticism actually has a beneficial effect on your life. I will explain all this in more detail shortly. I will also suggest some things we might be able to learn from this outlook, as well as a few difficulties it may cause. But first, a word about who Sextus was and what he wrote.

About Sextus as an individual, we know almost nothing. We know that he was a doctor, and a member of one of the major schools of medical thought at the time, the Empirical school. He lived during the period of the Roman Empire, and presumably somewhere within its boundaries. The best guesses place him as active around 200 CE, or maybe a little later, but this is far from certain. We dont know where he was from or where he lived. He wrote in Greek, but that really doesnt tell us much. In the Roman imperial period Greek was widely understood, especially among the educated classes, and widely used for intellectual purposes; for example, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, with whom Sextus was perhaps more or less contemporary, wrote his reflections to himself (usually called the Meditations) in Greek.

Sextus claim to fame rests on his extensive surviving writings. He identifies himself as a member of the Pyrrhonist tradition of skepticism, and his are the only complete surviving works from that tradition. Pyrrhonism traces its origins to the obscure figure (I mean, obscure to us) of Pyrrho of Elis (c.360270 BCE), who we are told accompanied Alexander the Great on his campaigns and met some naked wise men in India who supposedly inspired him. It is a fascinating and controversial question whether Pyrrhoand thereby, indirectly, the Pyrrhonist traditionwas actually influenced by some form of early Buddhism. But quite apart from the question of historical influence, many readers of Sextus do sense a certain affinity with aspects of Buddhism. I will touch on this again when we have seen some of the details.