Sextus Propertius - Poems

Here you can read online Sextus Propertius - Poems full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Carcanet, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Poems

- Author:

- Publisher:Carcanet

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Poems: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Poems" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Poems — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Poems" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

to TRICIA my life and travel companion qua nebulosa cauo rorat Meuania campo, et lacus aestiuis intepet Vmber aquis

- POEMS

He presents himself as a lover oppressed by an inescapable passion for his beloved, enslaved to her beauty and unable to write about anything else. As he invents countless variations on this basic scenario, his persona never changes. Where Catullus invites us to read his poetry as truly autobiographical and Ovid constantly lifts the mask of the earnest lover in order to wink at his readers, Propertius plays the comedic role of the absurdly obsessive lover but plays it straight. The result is poetry that presents itself as a sincere, authentic narrative of lived experience, but which is in fact a highly arch and self-ironising fiction. Propertian elegy sends up its own earnestness not by explicitly subverting its events and characters but by taking them to absurd extremes, never letting the pretence of authenticity slip. Propertius work belongs to the genre of Latin love elegy, which had, especially via Ovid, a vast influence upon the history of Western love poetry.

The particular discourse of the genre is a first-person narrative about an obsessive love affair with a pseudonymous mistress whose beauty and wit are celebrated while her indifference, unfaithfulness and cruelty are lamented. This obsession leads to a state of voluntary slavery which causes the poet to abandon all of his serious commitments to work, family and country. The metre of elegy is borrowed from the Greeks, and consists of couplets in which the first line is a six-foot hexameter (the metre of epic) and the second is a shorter pentameter. Couplets are generally end-stopped in terms of their sense: the hexameter sets up a thought and the pentameter completes it. This format lends itself to pointed, epigrammatic expression: elegiac couplets are also the metre of epigram in antiquity. The classical canon of Latin love elegy Cornelius Gallus, Tibullus, Propertius and Ovid was constructed by Ovid himself, who presents himself as its culmination and climax: Tibullus was your successor, Gallus, and Propertius was his; after them came I, fourth in order of time.

Ovid claims Propertius as his immediate predecessor, and Ovid is indeed Propertius greatest disciple: he picks up those elements of Propertian elegy that are couched in an elegant irony and takes them to outrageous extremes. But Propertius would not have recognised Ovids self-interested account of the elegiac tradition: he would have been quite furious to find himself described as Tibullus successor. When Propertius lays out for us the poetic tradition that he saw himself belonging to, he honours Catullus and positions himself as the immediate successor of Cornelius Gallus, but he writes his rival Tibullus out of the picture entirely. All agree that Gallus was the founder of the tradition of Latin love elegy; very little of his poetry survives, though Vergil and Propertius both address him frequently in their earliest works. An important military and political figure as well as a poet, he was one of the primary lieutenants of Octavian, the man who was to become Augustus, heir of Julius Caesar and the first Roman emperor. After Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra and captured Egypt, he left Gallus in charge of the country, an enormously powerful and sensitive position.

Before long, Gallus was accused of disloyalty and was compelled to commit suicide. After the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra, Octavian returned to Rome and set about a programme of national renewal to celebrate and consolidate the ensuing period of peace (and absolute hegemony). As part of that programme, the regime actively solicited a new kind of verse. Augustus did not want love poetry celebrating powerful women (like Cleopatra) and the men bewitched by them (like Antony, according to the history that was written by the winners); he wanted an epic celebrating the national destiny. Before long, the regime was actively encouraging Romans to return to traditional family values and later resorted to legislation to support that aim. In this atmosphere, Latin love elegy came to stand in contrast to patriotic epic; to traditional Roman values of family, nation and masculinity; and to several of the particular obsessions of the new regime of Augustus.

Why should I bear sons for my countrys triumphs? No child of mine shall be a soldier. When Propertius addresses these words to his mistress, swearing that he will never marry, he is pointedly rejecting the values of the new regime. This opposition between elegy and the emperor came to a head many decades later, when Ovid was exiled from Rome by Augustus; his outrageously cynical poetry about love and sex was an important factor in that punishment. Propertius himself, in his fourth and final book, moves away from an exclusive focus on love to write about Roman themes, but, given Propertius penchant for dry humour, the extent to which this should be interpreted as marking a sea-change is disputed. The themes of Latin love elegy can be easily enumerated, but what is more difficult is to give a sense of the qualities that set Propertius apart from the other writers in that genre. A century after Ovid, the critic and educator Quintilian revisited the canon of elegists: Of our elegiac poets Tibullus seems to me to be the most terse and elegant.

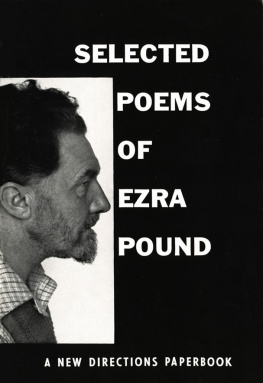

There are, however, some who prefer Propertius. Ovid is more lascivious than either, while Gallus is more severe. Quintilian was not often at a loss for words (this quote comes from a work in twelve books), but he seems here to be unable to capture a salient quality for Propertius in one or two adjectives, as he can easily do for the others. He simply says that some prefer Propertius, without being able to put his finger on quite why they do prefer him. To see what it is that has always made Propertius the choice of a select but discerning readership, it might be useful to contrast the responses of two modern poets in English who were obsessed with his work. A. E. E.

Housman and Ezra Pound both had significant encounters with Propertius in their youth, though for very different reasons. The two poets may have briefly overlapped in Edwardian London, but they came from different worlds and were on antithetical trajectories. Housman spent his early life as a private scholar working on difficult technical problems in Latin poetry until he had accrued such an international reputation as a classical scholar that he was appointed a senior professor of Latin, first at University College London and later at Cambridge. He always regarded his own verse as a private pursuit which was secondary to his scholarship. Pound, by contrast, gave up a very brief career in academia as quickly as possible in order to cultivate a flamboyant public life as a poet. Both men were attracted by the particular difficulties and beauties of Propertius, which they sought to address in ways that were diametrically opposed.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Poems»

Look at similar books to Poems. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Poems and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.