Daniel C. Richardson

In this book, I want to uncover some of the strange and surprising features of human thought and the ways we behave. This isnt a textbook where we traipse through each field of psychology in turn, like a diligent tourist visiting every site in the guidebook. Instead, each chapter begins with a simple question, then well look across all areas of psychology to find a scientific answer.

These questions may seem quite random, but through them youll learn about cutting-edge research in neuroscience and psychology, as well as the classic insights into our minds that psychologists have known for decades, but are still mostly unheard of outside our field. I also hope youll gain an appreciation of how we use the tools of science to understand the human mind, what we can conclude from our evidence and, just as importantly, what we cannot.

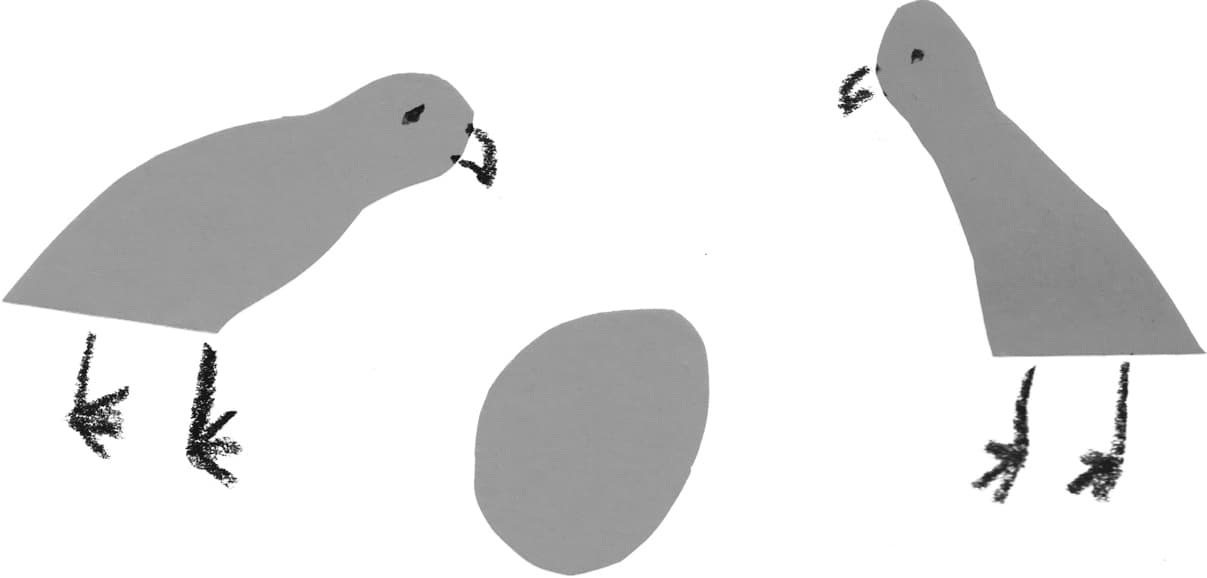

Lets start with the first question: why does the kakapo exist? Bright green and too fat to fly, its a parrot that waddles around the forests of New Zealand. When kakapos decide to start a family, the male emits a loud bass rumble to attract a female. Unfortunately, it takes a lot of energy to produce this noise think how large the bass speakers are in a club so the male kakapo can only sing his love song once every two-to-four years, when a particular tree drops a particular nutrient-rich fruit on the ground, the only place the bird can reach. The problem for the female kakapo is that its really hard to know where the bass sound is coming from.

If they do manage to find each other, a pair of kakapos may eventually produce eggs, which are highly sought after as a meal by various small mammals. They are drawn by the kakapos musty odour, which apparently resembles an old violin case. If a weasel attacks the nest, the kakapo has a defence: it stands very still with its wings spread out in an attempt to cover the eggs, but allowing the weasel to help itself.

The kakapo is one of the most charmingly inept creatures on this planet. They are so poor at the art of survival that only a handful exist; each kakapo actually has a team of people dedicated to keeping it alive. Heres the puzzle: the kakapo evolved to be this way. These flightless birds are winners in the survival of the fittest. So why on earth would evolution produce such a hot mess of a creature?

The key to understanding the kakapo is where it lives. Or rather, when. It evolved in New Zealand, a place that was covered in fruit-bearing trees for thousands of years. The kakapos didnt have to wait for a couple of years between feeds, and they were plentiful enough that females didnt have to trek through the forest to find a bass call because potential mates were thick on the ground. For thousands of years, kakapos did not have any predatory land mammals that would eat their eggs (those would arrive with human settlers). The only predator that threatened the birds happy existence was a large eagle. Therefore, if you live in a forest and have green feathers, a good defence against an overhead predator is to stand very still and cover your nest with your wings.

The kakapo is a highly specialised animal, perfectly evolved for a world that no longer exists. In many ways, we too are like the kakapo. Human beings evolved in a world with a particular habitat, in social groups of a particular size, with behaviours and diets perfectly suited to the challenges and opportunities around us. We no longer live in that world. Now we live in habitats of high-population densities, with nutrition tailored to our desires, rather than our needs, and engage in activities such as reading, writing and operating machinery that were alien to our species until fairly recently in human history.

We live in an illusion of rationality. It is possible for us to make reasoned, sensible choices, illuminated by carefully collected evidence, so we feel that most of our decisions are rational and enlightened. However, we did not evolve to be rational and sensible. Like the kakapo, we evolved in response to different pressures. Our brains were shaped for a different purpose.

In this book, well see that some of our fundamental beliefs about thought simply arent borne out by psychological science. People do not always like things jobs, partners, or products that are rewarding. We do not like choice. Our eyes do not deliver an accurate view of the world and our memory is not there to record it. Although we believe in fairness, equality and tolerance, our minds are built for prejudice, assumption and bias. This doesnt mean we are stupid or poorly evolved. It means that, just like the hapless kakapo, we are built for a different world.

Our social networks now expand across the globe. Our micro-behaviour and biology is constantly monitored by smart technology we install in our homes and wear on our bodies, and we can have our individual genome read as easily as tea leaves. To understand the impact of this new technology, we have to understand the lumbering humans that are plugged into it. Thats what well explore in this book. How do we form social connections to other people? What does our behaviour tell us about our thoughts? How do our genes determine who we are? Each chapter will begin with a simple question, and end by giving insight into your own mind, the people around you and how we all will fit into the new world emerging around us.

Mind vs mind

Where are our thoughts?