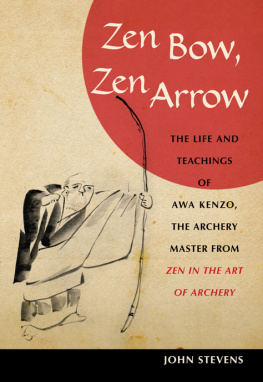

Zen in the Art ofArchery

The Para-RationalPerspective*

By BroomhandleBooks

SmashwordsEdition

Copyright 2015 BroomhandleBooks

All rights reserved. No partof this publication may be reproduced, scanned, distributed ortransmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database orretrieval system without the prior written permission of thepublisher. All inquiries should be addressed to

For eword

Broomhandle Books created its sectionof Continuing Education pieces to provide readers with thoughtfulconsiderations on books read by others. Instead of the dashed offreviews one might find at retailers or club websites, thesepieces are meant to provide a more in-depth consideration of thebooks themselves.

In some cases, the manuscriptspresented in this Continuing Education series are merely paperswritten by undergraduate and graduate students assigned certainsubjects. In other cases, these pieces are written as non-scholarlymusings by people fascinated by certain subjects. In thisparticular case, we found the paper interesting for content as wellas the fact that the author actually included comments on the papermade by the professor teaching the class for which the paper waswritten.

Whether trying to determine if theactual book is worth your time reading, trying to compare your ownthoughts on the subject with others, or simply trying to engageyour mind in consideration of certain topics, we believe thesepieces will offer useful insights.

Whatever their source, we certainlyenjoyed reading these manuscripts and hope you enjoy them, aswell.

The Editors at BroomhandleBooks

November 1, 2015

ZEN IN THE ART OFARCHERY

The Para-RationalPerspective*

Zen practice of any art ismystical, an end in itself, and an understanding which passes fromteacher to student via minimalist language and repetitivepractice/discipline. As Eugen Herrigel explains in Zen in the Art of Archery , arts molded by Zen merge the art and the artist into asingle reality in which the artist is a vehicle of the divine, avessel through which the divine expresses itself. Such a vessel, ofcourse, is empty and void of self.

The debate between philosophers andscientists over whether the value of knowledge" is to know theworld or to change the world, plays itself out in the juxtapositionof the Western-conceived sport of archery and Herrigelsdiscussion of the Zen molded art of archery. According toHerrigel, the art of archery reveals itself in spiritual exercisesto discipline the mind, not in bodily exercises to build physicalstamina in a rational and progressive study

of technique. The Zen molded art ofarchery seeks to develop life as an art form; the Western sport ofarchery endeavors to hit the target.

Zen's molding of arts as described byHerrigel requires the right presence of mind; discipline; loss ofself; and, when words finally do not suffice to instruct,transference of spirit from Master to student. With an objective tobecome part of the greater whole, part of the spirit, Herrigelhad

to relinquish his Western habits ofrationalizing, thinking, and analyzing in order to learn to waitand to realize in Nature there are correspondences which cannotbe understood (Herrigel, page 57).

Using paradoxes to describe the Zen ofarchery, Herrigel cal1s the art "artless", the archersimultaneously the aimer and the aim, and shooting becomesnon-shooting". Perceptual reality plays no role in the developmentof this art, making it, thus, anathema to the rational construct ofart or sport as known in the Western world. Perceptual knowingthrough the senses went unrewarded for Herrigel when he learned atechnique to loose the shot. His master sought

from him enlightenedunselfconsciousness, instead, so the shot would loose itself. Infact, the bow and arrow, Herrigel learned, are superfluous to thereal attainment in this art, which is to accomplish somethingwithin ones self, not outwardly.

Elimination of self permeatesHerrigels exposition of Zen molded archery. Life is somethingwhich no Zen adept primarily inhabits as his. A completeannihilation of the confused rational assessment of life inrelation to the individual is replaced by an all-embracing Truth(Herrigel, page 10) that becomes the bedrock of Life. Zen, ineffect, teaches concentration, breathing, and meditation as do allother forms of Buddhism. Zen molded arts harness those teachingsinto art forms which serve to create human vehicles purely focusedon the moment through which the spirit may expressitself.

Just as Zen refuses to invest anyvalue in self, it also refuses to assign any significance toobjects. Upon his departure from his Master, Herrigel received agift of the Master's best bow with an instruction to use it andthen, when ready to die, to destroy the bow. Such a directivedenies any value to the bow, its history, or its craftsmanship. TheZen focus remains always on the spirit

and becoming one with it. Like theman, the bow has been a vessel for the spirit and it too, like theman in death, deserves the dignity of the spirit's embracethrough destruction of its outer form."

Zens contribution to a mans life isunderstood through doing or practice, but nearly impossible toarticulate. Despite centuries of Zen practitioners, a book ascompact as Herrigels accommodates descriptions of the fewmanuscripts that offer any insight into the Zen molded arts. Fromthis, one must appreciate Zen as mystical if only because Zenmasters do no more than hint at their own experiences in pursuingand accomplishing the skills and discipline associated with the Zenarts.

Wrapped in impenetrable darkness, Zenmust seem the strangest riddle which the spiritual life of the Easthas ever devised: insoluble and yet irresistibly attractive(Herrigel, page 8).

NOTES

*The definition ofpara-rational used in this paper comes from a course taught atCalifornia State University Dominguez Hills, which is: non-rational alternatives in modern culture, focusing on thenon-logical, the visionary, and the religious/mystical. For thecomplete definition of para-rational used in that , please referto: http://www.csudh.edu/hux/syllabi/542/course_3.html

Professors reaction tothis paper:

An intelligent, clearcommentary on Herrigels Zen in the Art ofArchery . In your discussion, you might havemade clearer the difference between the Western and Zen approachesto archery. I really dont think most Western archers undertakearchery primarily as a means to build physical stamina in arational and progressive study of technique. This, I assume, is ahappy by-product. Archery is primarily a sport, not an art, whichinvolves competition and a pragmatic end (to hit the bulls-eye).In brief, it is an end in itself. John Cage, a fan of Zen, relatesthat the most revered Zen archery master in Japan seldom ever hitsthe target and never the bulls-eye! Let me also note that theschool of Zen which Herrigel participated in is the Rinzai schoolwhich does indeed emphasize repetitive practice/discipline, butthe Soto school deemphasizes these, asking its students only to sitquietly emptying the mind; even Satori is not sought as a necessarygoal. Also, though orthodox Christianity and Zen-Buddhism are light yearsapart, their mystical traditional as argued by Aldous Huxley in his The Perennial Philosophy bear profound similarities; after all, the Western-Christiantradition until the Renaissance could hardly be consideredrational.

WORKS CITED

Herrigel, Eugen. Zen in the Art ofArchery. New York, Knopf Doubleday, 1989.

OTHER TITLES PUBLISHEDBY

BROOMHANDLE BOOKS

Remington 1858 Revolver in Gone withthe Wind

By John Vlander

Dear DarlingLoulie

By Rachel Taylor Hall

From the Life of the Colditz Mayor:Georg Leuschner (1549-1620)

By Johannes Loschke

The Plight of the20 th Century Man in The Stranger

By Broomhandle Books

Next page