Eugen Herrigel - Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937)

Here you can read online Eugen Herrigel - Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Lightning Source Inc, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

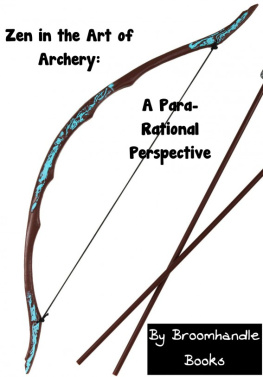

- Book:Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937)

- Author:

- Publisher:Lightning Source Inc

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Zen in

the Art

of Archery

Eugen Herrigel

Translated by R. F. C. Hull

Vigeo Press

Originally Published 1953.

Public Domain.

Vigeo Press Reprint, 2018

ISBN

Paperback 978-1-941129-94-4

Epub 978-1-941129-93-7

Contents

Preface

In 1936 a lecture which I had delivered to the German-Japanese Society in Berlin appeared in the magazine Nippon under the title The Chivalrous Art of Archery. I had given this lecture with the utmost reserve, for I had intended to show the close connection which exists between this art and Zen. And since this connection eludes precise description and real definition, I was fully conscious of the provisional nature of my attempt.

In spite of everything, my remarks aroused great interest. They were translated into Japanese in 1937, into Dutch in 1938, and in 1939 I received newsso far unconfirmedthat an Indian translation was being planned. In 1940 a much improved Japanese translation appeared together with an eyewitness account by Prof. Sozo Komachiya.

When Curt Weller, who published The Great Liberation , D. T. Suzukis important book on Zen, and who is also bringing out a carefully planned series of Buddhist writings, asked me whether I agreed to a reprint of my lecture, I willingly gave my consent. But, in the conviction of having made further spiritual progress during the past ten yearsand this means ten years of continual practiceand of being able to say rather better than before, with greater understanding and realization, what this mystical art is about, I have resolved to set down my experiences in new form. Unforgettable memories and notes which I made at the time in connection with the archery lessons, stood me in good stead. And so I can well say that there is no word in this exposition which the Master would not have spoken, no image or comparison which he would not have used.

I have also tried to keep my language as simple as possible. Not only because Zen teaches and advocates the greatest economy of expression, but because I have found that what I can not say quite simply and without recourse to mystic jargon has not become sufficiently clear and concrete even to myself.

To write a book on the essence of Zen itself is one of my plans for the near future.

Eugen Herrigel

Chapter I.

At first sight it must seem intolerably degrading for Zenhowever the reader may understand this wordto be associated with anything so mundane as archery. Even if he were willing to make a big concession, and to find archery distinguished as an art, he would scarcely feel inclined to look behind this art for anything more than a decidedly sporting form of prowess. He therefore expects to be told something about the amazing feats of Japanese trick-artists, who have the advantage of being able to rely on a time-honored and unbroken tradition in the use of bow and arrow. For in the Far East it is only a few generations since the old means of combat were replaced by modern weapons, and familiarity in the handling of them by no means fell into disuse, but went on propagating itself, and has since been cultivated in ever widening circles. Might one not expect, therefore, a description of the special ways in which archery is pursued today as a national sport in Japan?

Nothing could be more mistaken than this expectation. By archery in the traditional sense, which he esteems as an art and honors as a national heritage, the Japanese does not understand a sport but, strange as this may sound at first, a religious ritual. And consequently, by the art of archery he does not mean the ability of the sportsman, which can be controlled, more or less, by bodily exercises, but an ability whose origin is to be sought in spiritual exercises and whose aim consists in hitting a spiritual goal, so that fundamentally the marksman aims at himself and may even succeed in hitting himself.

This sounds puzzling, no doubt. What, the reader will say, are we to believe that archery, once practiced for the contest of life and death, has not survived even as a sport, but has been degraded to a spiritual exercise? Of what use, then, are the bow and arrow and target? Does not this deny the manly old art and honest meaning of archery, and set up in its place something nebulous, if not positively fantastic?

It must, however, be borne in mind that the peculiar spirit of this art, far from having to be infused back into the use of bow and arrow in recent times, was always essentially bound up with them, and has emerged all the more forthrightly and convincingly now that it no longer has to prove itself in bloody contests. It is not true to say that the traditional technique of archery, since it is no longer of importance in fighting, has turned into a pleasant pastime and thereby been rendered innocuous. The Great Doctrine of archery tells us something very different. According to it, archery is still a matter of life and death to the extent that it is a contest of the archer with himself; and this kind of contest is not a paltry substitute, but the foundation of all contests outwardly directedfor instance with a bodily opponent. In this contest of the archer with himself is revealed the secret essence of this art, and instruction in it does not suppress anything essential by waiving the utilitarian ends to which the practice of knightly contests was put.

Anyone who subscribes to this art today, therefore, will gain from its historical development the undeniable advantage of not being tempted to obscure his understanding of the Great Doctrine by practical aimseven though he hides them from himselfand to make it perhaps altogether impossible. For access to the artand the master archers of all times are agreed in thisis only granted to those who are pure in heart, untroubled by subsidiary aims.

Should one ask, from this standpoint, how the Japanese Masters understand this contest of the archer with himself, and how they describe it, their answer would sound enigmatic in the extreme. For them the contest consists in the archer aiming at himselfand yet not at himself, in hitting himselfand yet not himself, and thus becoming simultaneously the aimer and the aim, the hitter and the hit. Or, to use some expressions which are nearest the heart of the Masters, it is necessary for the archer to become, in spite of himself, an unmoved centre. Then comes the supreme and ultimate miracle: art becomes artless, shooting becomes not-shooting, a shooting without bow and arrow; the teacher becomes a pupil again, the Master a beginner, the end a beginning, and the beginning perfection.

For Orientals these mysterious formulae are clear and familiar truths, but for us they are completely bewildering. We have therefore to go into this question more deeply. For some considerable time it has been no secret, even to us Europeans, that the Japanese arts go back for their inner form to a common root, namely Buddhism. This is as true of the art of archery as of ink painting, of the art of the theatre no less than the tea ceremony, the art of flower arrangement, and swordsmanship. All of them presuppose a spiritual attitude and each cultivates it in its own wayan attitude which, in its most exalted form, is characteristic of Buddhism and determines the nature of the priestly type of man. I do not mean Buddhism in the ordinary sense, nor am I concerned here with the decidedly speculative form of Buddhism, which, because of its allegedly accessible literature, is the only one we know in Europe and even claim to understand. I mean Dhyana Buddhism, which is known in Japan as Zen and is not speculation at all but immediate experience of what, as the bottomless ground of Being, cannot be apprehended by intellectual means, and cannot be conceived or interpreted even after the most unequivocal and incontestable experiences: one knows it by not knowing it. For the sake of those crucial experiences Zen Buddhism has struck out on paths which, through methodical immersion in oneself, lead to ones becoming aware, in the deepest ground of the soul, of the unnamable Groundlessness and Qualitylessnessnay more, to ones becoming one with it. And this, with respect to archery and expressed in very tentative and on that account possibly misleading language, means that the spiritual exercises, thanks to which alone the technique of archery becomes an art and, if all goes well, perfects itself as the artless art, are mystical exercises, and accordingly archery can in no circumstances mean accomplishing anything outwardly with bow and arrow, but only inwardly, with oneself. Bow and arrow are only a pretext for something that could just as well happen without them, only the way to a goal, not the goal itself, only helps for the last decisive leap.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937)»

Look at similar books to Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Zen in the Art of Archery (9781941129937) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.