FOREWORD

WHEN I ARRIVED IN JAPAN I had already every intention of studying the archery of Japan, for I had long been a devotee of the English long bow at home. My first few months in Japan passed busily without my doing anything about it, and it was not until May of that year that I went to the Butokuden, the Hall of Martial Virtue, next to the Heian Shrine in Kyoto to see the archery there. I had been in Peking during April for a short visit and had there visited the famous Bow and Arrow street where I acquired several Chinese bows. This really started me on my investigations into Oriental archery so that when I got back to Kyoto I made a point of visiting the Hall of Martial Virtue at once.

On the day of my first visit I was allowed to come in and sit in the hall from which the archers shoot and watch the shooting going on, as tourists are allowed to do. Since I spoke Japanese I was soon busy asking questions and answering those that they asked me concerning American archery. But when I said that I would like to learn to shoot Japanese style, there was a general shaking of heads. A foreigner might try, of course, but the consensus seemed to be that he wouldn't get far!

One man there, however, Mr. Toshisuke Nasu who, perhaps just for the sake of argument, took my side and declared that in his opinion any man with the necessary intelligence and patience could learn, no matter whether Japanese or foreign. Then and there he generously offered to begin teaching me the very next day in order to prove that Japanese archery could be learned and practiced by a foreigner.

Shortly afterwards we left the Butokuden together and went to his house where we had ceremonial tea and talked a while, after which we proceeded to a fletcher's shop where he ordered arrows for me, first, a blunt featherless practice arrow, for it would be a long time, he assured me, before I would be able to shoot at a target with real arrows.

At that time I had rooms in a small sub-temple within the walls of the great Zen-Buddhist Monastery Shkukuji, north of the Imperial Palace grounds. The priest who lived there was retired and let his spare rooms to studentsand I had been fortunate enough to get one. The place was wonderfully quiet, and my room looked out on a garden beyond which stood a deep grove of tall bamboos. For the next few months my friend and instructor, Mr. Toshisuke Nasu, came almost daily, early in the morning, and taught me the art of Japanese archery.

He lent me a weak bow of his own to begin with and brought his own makiwara or straw-tub, a great cylindrical bundle of straw tightly bound together and sometimes fitted into a tub, into which the beginner shoots end-on from a distance of four or five feet, using a blunt featherless arrow until his form is so nearly perfected that he can be trusted with real arrows.

It was hard work. Months slipped by, and still I stood before the makiwara ceaselessly discharging arrows (the featherless variety) into it, and pulling them out again, while Mr. Nasu stood to one side commenting freely on each shot. Some days everything would go wrong. Some days he would note a considerable improvement. Gradually, very gradually, I learned to keep the grip on the bow so relaxed that the bow on being released began to show a tendency to turn in the hand. Day by day this tendency grew stronger. Soon the string would describe a half circle and the bow would fetch up with the back facing straight towards me; and all the time Mr. Nasu saw to it that I did nothing with my hand to help it turn. The turning of the bow in the hand is not prized so much because of its beauty but because it is a phenomenon that naturally occurs when the grip of the bow hand is exactly as it should be. It took several months to come, but at last it did happen that the string came round smartly and struck me on the back of the wrist, and soon this was happening regularly.

Meanwhile Mr. Nasu had been occasionally writing out short descriptions of the various steps in archerythe stance, the draw, holding, releasing and I would translate them, while discussing them with him. Hence properly speaking I am the translator, not the coauthor of the text which follows. However, I have put in much here and there to make it easier for the American archer to understand, and, since we discussed each detail at length as it came up, the result can fairly be called a joint production.

It has been done in what little time I have been able to spare from my study of Japanese art and language. Others became interested and helped translate and joined in the discussions. The first was Antoon Hulsew, a fellow student of mine at Ley den who was in Kyoto for just a year, during which time he too studied archery. Dr. C. Fahs, a scholar in economics and government, was another. These two, Mr. Nasu, and I used to meet from time to time in the evening, and among us we translated a considerable part of the Shagakuseis i.e. Orthodox School of the Study of Shooting, an old Chinese text on archery written during the Ming dynasty. Mr. Hulsew was with us only at the start of that work, but Dr. Fahs continued working with us for many months. It is a very interesting text and I feel sure that American archers would much appreciate it.

This present book is not a treatise on Japanese archery in general, but a short statement of the aims and methods of archery as practiced in Japan, or at any rate as it has been taught to me. For there are many schools of archery in Japan with all sorts of different traditions. Some emphasize one thing, others another, but on the whole it would seem that they really differ only in nonessentialssmall tricks of technique and matters of ceremonial form. When it is a question of holding at full draw and the release, for example, they are all in agreement and indeed could hardly differ.

Accordingly the reader may be sure that he has here a fair presentation of a typical style of Japanese shooting, which, in its fundamental aspects, does not differ materially from other styles of Japanese, or indeed Oriental, archery.

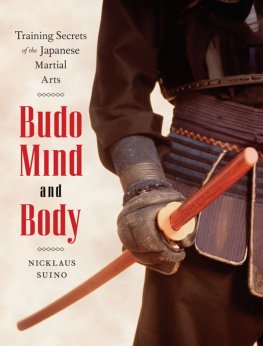

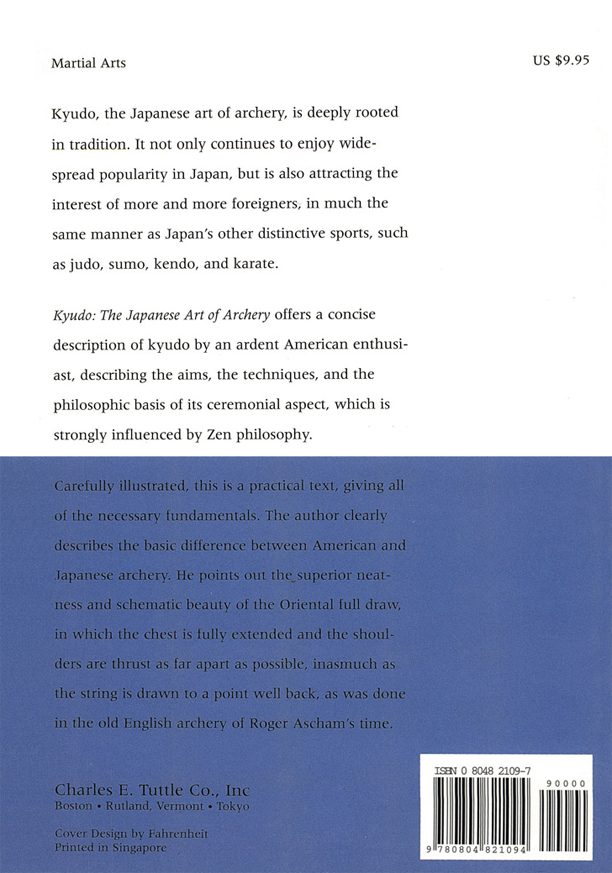

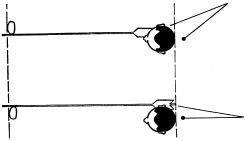

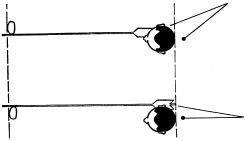

To the Westerner by far the most interesting thing about the archery of the Far East is the fact that in both China and Japan the string is still drawn to a point well behind, as was done in the old English archery of Roger Ascham's time. That this is an advantage in some ways will, I think, be plain from the diagrams which show the two positions, drawn as if seen from a point directly above the archer's head. The first diagram illustrates the American full draw, and shows how the elbow of the draw arm must form an obtuse angle with the line of the two shoulders as long as the string is not drawn well behind the ear.

The second diagram shows the relative positions of the rear elbow and the shoulders in the Oriental full draw. Note that the entire pull of the string is shifted directly onto the shoulder of the draw arm, instead of continuing to pull on the elbow as in the American method.

AMERICAN AND JAPANESE FULL DRAW

Note that with the American full draw (upper sketch), in which the string is not drawn well behind the ear, the elbow is not in line with the shoulders, and that in the Japanese full draw (lower sketch) it is in line, thus shifting the entire pull of the string onto the shoulder of the draw arm instead of continuing it on the elbow as in the American method.