CONTENTS

PART ONE:

PART TWO:

PART THREE:

PART FOUR:

PART FIVE:

PART SIX:

PART SEVEN:

PART EIGHT:

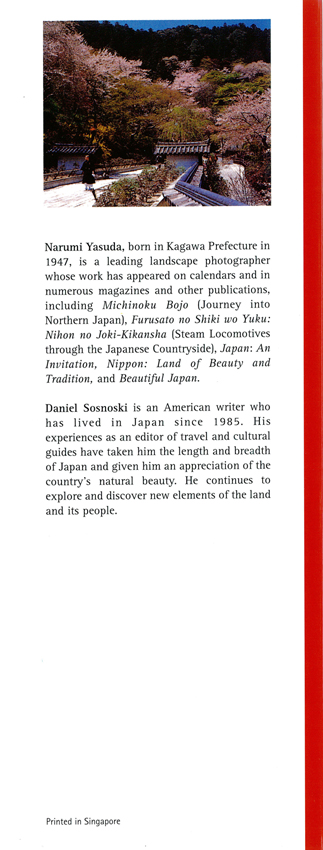

All photographs on the cover and in the text of this book were taken by Narumi Yasuda, except for the photographs on p. , which were taken by Frank Leather.

Published by Tuttle Publishing,

an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.,

with editorial office at 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT 05759 U.S.A.

1996 by Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Co., Inc.

All rights reserved

LCC Card No. 96-62169

ISBN: 978-1-462-91153-0 (ebook)

First edition, 1996

Fourth printing, 2001

Distributed by:

Japan & Korea

Tuttle Publishing Japan

Yaekari Building 3rd Floor, 5-4-12

Osaki Shinagawa-ku,

Tokyo 141-0032

Tel: 81 (03) 5437 0171

Fax 81 (03) 5437 0755

North America

Tuttle Publishing

Distribution Center

Airport Industrial Park

364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436

Tel: (802) 773 8930

Fax: (802) 773 6993

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd,

61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12

Singapore 534167

Tel: (65) 6280 1330

Fax: (65) 6280 6290

Email: inquiries@periplus.com.sg

Web site: www.periplus.com

Printed in Singapore

List of Line Illustrations

page 11

6. 31

PART ONE

Holidays

and Festivals

SHOGATSU

New Year's Day

In Japan , as in other Asian countries, the New Year's holidays have always had a special significance. They are by far the most importantand the longestholidays in the Japanese calendar. For almost a week the bustling Japanese economy practically comes to a standstill. Schools, companies, and stores close down; and trains, planes, and highways are packed as millions make their way to their hometowns or to ski resorts and Onsen for the festivities. From December 30, when the holiday actually begins for most people, huge cities like Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya take on an eerie quietness until the great rush back home and a return to the office starts on January 4 or 5.

The holiday is especially a time for family and friends. It is also a time for parties, reunions, formal visits, and a host of New Year's celebrations and games that give the season its special flavor. Just like holidays in other parts of the world, one of the special activities is lots of hearty eating and drinking along with good fellowship and cheer. Traditional New Year's foods are prepared well in advance to minimize cooking and household chores. For example, mochi, a thick, gooey cake of pounded, cooked rice, is prepared so that it can be served at breakfast, lunch, or any other time of the day. And osechi ryori, a seemingly endless array of cold tidbits served from stacked lacquerware boxes, is prominently featured at all New Year's mealsfrom simple snacks to elegant banquets.

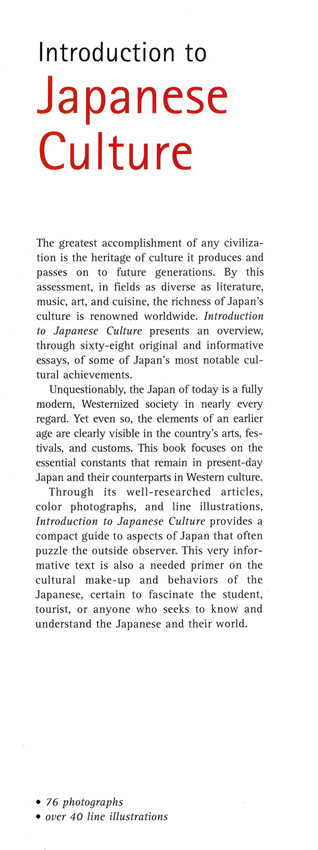

Traditionally, New Year's preparations have included ritual housecleaning, the clearing up of all debts, new kimono for each child in the family, and the hanging of special decorations. These ancient customs are still carefully preserved by many Japanese families. A walk down any quiet street during the holidays reveals a fascinating blend of the old and the new: kadomatsu decorations, made of bamboo stalks and pine boughs, standing beside the shuttered entrances of skyscrapers; Shinto shimekazari, straw ropes strung with little angular strips of white paper, hanging across the front of parking lots, supermarkets, and electronic game centers. Even though the symbolism of some of these customs may be lost to many people, to Japanese the holidays would never seem the same without them.

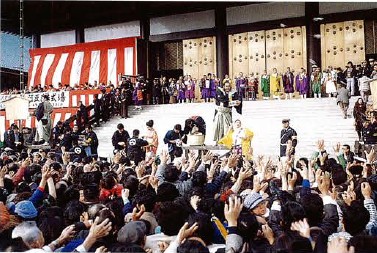

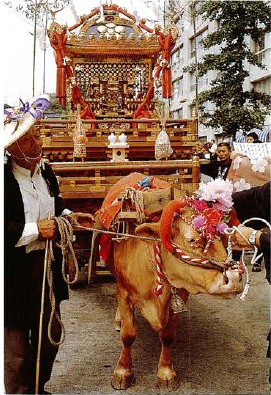

In these and many other ways, New Year's in Japan is really quite similar to the holiday season in Western countries. Where Americans send Christmas greetings to their friends, Japanese exchange New Year's cards. Because of the special extra crews hired by the post office just for this purpose, Japanese receive their greeting cards all at once on New Year's Day itself if the postman is on time. And the custom that many Americans observe by attending church on Christmas Eve finds its counterpart in Japan, where a visit to a Shinto shrine or a Buddhist temple is traditional during the early hours of New Year's Day. Many people, especially women and children, dress in kimono for these hatsumode visits, a beautiful custom that makes the season even more festive.

SETSUBUN

Bean-Throwing Ceremony

There are probably many foreigners in Japan who first learned of setsubun after the startling experience of seeing Japanese friends or acquaintances throwing beans around for apparently no reason. Most Japanese can probably offer at least a superficial explanation for this custom, but there are also doubtlessly many who have never given serious thought to the full significance of setsubun . Observance of this holiday may actually be declining.

As a traditional custom, setsubun is preserved in part by somewhat nontraditional means. TV and movie personalities, for example, publicize the event by appearing in front of well-known shrines to throw beans. Other bean throwers to which the media may turn are sumo wrestlers, otherwise known for their salt throwing. Celebrities thus serve to remind the Japanese of their cultural heritage, even if the busy public takes little or no time to reflect on it. Many holidays are rooted in the celebration of the seasons and are easily lost in the shuffle of modern urban life. For most Japanese office workers, holidays are significant only if they provide a day off; their original meaning or purpose is in most cases either forgotten or irrelevant.

Still, holidays are preserved and remembered not by their meaning but rather by the activities associated with them. Though few Japanese are likely to know or think about the origin of setsubun , there are many who faithfully follow the custom of scattering beans on February 3. Originally, when the lunar calendar was in use, setsubun took place at the beginning of spring, as the name suggests. To shout " Oni wa soto , fuku wa uchi" was therefore not only a kind of prayer, but also an affirmation of a new beginning: out with old troubles, in with new hope. The Japanese make much of New Year's cleaning, but even in February there is probably much of the same spirit among those who follow the setsubun custom today, regardless of whether they really believe that they are driving away demons.