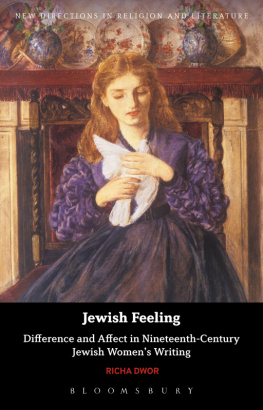

Jewish Feeling

NEW DIRECTIONS IN RELIGION AND LITERATURE

This series aims to showcase new work at the forefront of religion and literature through short studies written by leading and rising scholars in the field. Books will pursue a variety of theoretical approaches as they engage with writing from different religious and literary traditions. Collectively, the series will offer a timely critical intervention to the interdisciplinary crossover between religion and literature, speaking to wider contemporary interests and mapping out new directions for the field in the early twenty-first century.

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BLOOMSBURY:

Blake. Wordsworth. Religion, Jonathan Roberts

Dante and the Sense of Transgression, William Franke

Do the Gods Wear Capes? Ben Saunders

Englands Secular Scripture, Jo Carruthers

Forgiveness in Victorian Literature, Richard Hughes Gibson

Glyph and the Gramophone, Luke Ferretter

John Cage and Buddhist Ecopoetics, Peter Jaeger

Late Walter Benjamin, John Schad

The New Atheist Novel, Arthur Bradley and Andrew Tate

Rewriting the Old Testament in Anglo-Saxon Verse, Samantha Zacher

Victorian Parables, Susan E. Coln

FORTHCOMING:

Faithful Reading, Mark Knight and Emma Mason

The Gospel According to David Foster Wallace, Adam Miller

Long Story Short, Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg and Peter S. Hawkins

Pentecostal Modernism, Stephen Shapiro and Philip Barnard

Romantic Enchantment, Gavin Hopps

Sufism in Western Literature, Art and Thought, Ziad Elmarsafy

The Willing Suspension of Disbelief, Michael Tomko

Jewish Feeling

Difference and Affect in Nineteenth-Century Jewish Womens Writing

Richa Dwor

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This book is dedicated to my parents, Gila Golub and Mark Dwor.

Contents

Parts of this book have appeared elsewhere as articles. A version of can be found in The Racial Romance of Amy Levys Reuben Sachs, English Literature in Transition 55.4 (July 2012): 46078. I thank Oxford University Press and Robert Langham for allowing me to reproduce both here in modified form. Permission to publish an extract from Grace Aguilars poem Lines, 11 Aug 1834 is granted courtesy of the Jewish Museum, London.

The research in this book began life as my doctoral thesis and I am happy to have the opportunity to acknowledge with gratitude the Postgraduate Teaching Fellowship that I was awarded by the School of English at the University of Nottingham. I am as fortunate now as I was during those years to have had Professor Josephine Guy as my supervisor. I found my first professional home in the Victorian Studies Centre at the University of Leicester, and I thank my colleagues there, particularly Professor Gail Marshall, for several years of wonderful collaboration, community and encouragement. I formed another kind of family at the Nottingham Liberal Synagogue, where I was warmly welcomed, actively listened to and amply fed. There I met my great friend, Rabbi Tanya Sakhnovitch, whose guidance has been so valuable to this project. Elizabeth Fry and Kimberly ODonnell selflessly read draft chapters, which has earned each my undying gratitude and baked goods on demand. Daniel Weston has, in every way, made completion of this book possible.

Following 150 days of flooding and becalmed for ten further months in an animal-laden ark, Noah finally opens a window to send out a dove to see if the waters were abated from off the face of the ground (Gen. 8:8). He does so on three occasions. Having found nowhere to land, the dove returns weary from her first excursion and is welcomed by Noah in a protective embrace; he put forth his hand, and took her, and pulled her unto him into the ark (Gen. 8:9). The next time the dove is sent forth, she returns with an olive leaf in her beak, signifying the nearby presence of dry and fruitful land. After her final release she returned not again unto him any more (Gen. 8:12), indicating that the captivity and protection represented by Noah have been superseded by the possibility of true freedom, as well as the promise that Noah and his inmates will soon be released from the confines of the ark. The image of the dove reappears in a number of Jewish and Christian biblical texts and has since attained a status in culture as a symbol of peace. For example, in Song of Songs, having made a range of comparisons to other animals the speaker uses the dove to indicate concealed beauty:

O my dove, that art in the clefts of the rock, in the secret places of the stairs, let me see thy countenance, let me hear thy voice; for sweet is thy voice, and thy countenance is comely. (Song of Songs 2:14)

In Christian iconography, the dove represents the Holy Spirit in its appearance at the moment of Jesuss baptism in which he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove (Mt. 3:16) and the Holy Ghost descended in a bodily shape like a dove upon him (Lk. 3:22). With its enduring connotations of freedom, innocence and humility the dove has been used in visual art beyond religious iconography as a symbol of peace in political contexts. Notably, Pablo Picassos Dove of Peace drawings were reproduced to benefit various peace congresses held throughout Europe during the mid-twentieth century.

Rebecca Solomon (183286) painted The Wounded Dove (seen on the cover of this book), a watercolour, in 1866. It depicts a woman, with downcast eyes, cradling a dove to her chest in both hands. The dove appears to have a broken wing, and its head points upwards although its face does not intercept the womans gaze. Her full lips are set in a reposeful smile and her expression is meditative. Her attire and the setting are markers of realistically rendered middle-class Victorian domesticity. She wears a purple silk blouse with elaborately ruched sleeves, embellished by black braid at the neck. Her slim waist is emphasized by a buckled belt, beneath which flows a full black skirt, spread to cover most of the chair on which she sits. Upholstered in red velvet and featuring twisted wooden columns and a carved headrest, the chair is rather broad and throne-like. It is positioned before a fireplace, and on the mantelpiece (itself upholstered after a fashion in a fringed red cloth), there is a symmetrical display of fans, vases and ceramic plates in fashionable chinoiserie patterning. The dove in this painting would have presented an unmistakeable biblical reference to its Victorian viewers, who were schooled in spotting such symbols in images and language. It bears an allegorical resonance as a symbol of peace, and by providing succour to the wounded bird the woman enacts a contemporary parable of the rehabilitation of peace in the home. In upholding the popular valorization of womens domestic spiritual influence, Solomon furthermore replaces Noahs patriarchal embrace of the dove with a young womans, and she substitutes the ark for a well-appointed parlour.

Solomon exhibited at the Royal Academy of Art between 1852 and 1868, as well as at other galleries in London. Her father was a merchant and she was one of eight siblings in a Jewish family that engaged actively in the arts, especially painting. A gradual increase in critical attention to her work, usually alongside other neglected Victorian female painters or in the context of her more famous brothers, indicates a trend for recovering female voices in fields where the focus has traditionally been on male figures. Nevertheless, by staging an affective transmission between a woman and the dove she offers it compassionate shelter, it offers her the possibility of renewed peace the painting may be viewed as an engagement with Genesis that considers possibilities for womens interventions into Jewish interpretive practices as well as the formation of Jewish identity within the new conditions of political emancipation.

Next page