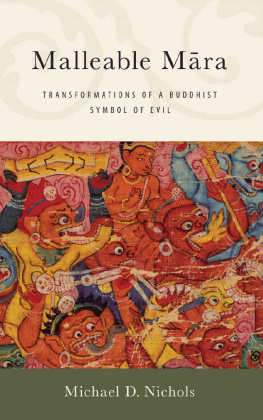

Malleable Mra

Malleable Mra

Transformations of a Buddhist Symbol of Evil

MICHAEL D. NICHOLS

Cover art: Maras Retinue, Folio from an Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita (The Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 Verses). Nepal, 11th century. Opaque watercolor on palm leaf, 2 5 in. (5.71 12.7 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). From the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Museum Associates Purchase (M.72.1.22). https://collections.lacma.org/node/238328.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2019 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nichols, Michael D., 1977 author.

Title: Malleable Mara : transformations of a Buddhist symbol of evil / Michael D. Nichols.

Description: Albany : State University of New York, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018017081 | ISBN 9781438473215 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438473239 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Good and evilReligious aspectsBuddhism. | Buddhist art and symbolism.

Classification: LCC BQ4570.G66 N53 2019 | DDC 294.3/4216dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018017081

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Illustrations

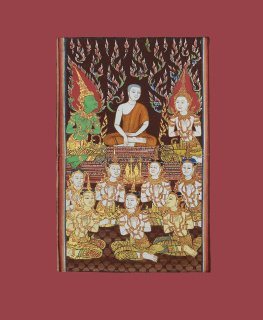

All images appear courtesy of the Huntington Archive of The Ohio State University.

Note on Reprints

Earlier versions of portions of appeared in Mara Re-imagined: The Evil One in Changing Contexts, Pacific World , 3.16, 2014: 118. The latter article also had the benefit of presentation at the Numata Symposium for the Institute of Buddhist Studies, Berkeley, California.

I am grateful to the editors of the journals Religions of South Asia and Pacific World for permission to reprint portions of this work in revised form.

Note on Translations

Unless otherwise noted, translations from the Pli and Sanskrit in

Acknowledgments

This project started as the musings of a Masters student on his balcony overlooking the southwest Ohio cornfields nearly two decades ago. It has had numerous benefactors between that point and the form it now takes in this book. My mentors at Miami University of Ohio were the first individuals to help sustain my work. Julie Gifford shepherded me through an independent study on secondary literature involving Mra, while my devoted adviser, Liz Wilson, initiated me into the world of Buddhist and Religious Studies and aided me in crafting a Masters thesis that planted the seed of this larger project. I am grateful for her wisdom and generosity. During my time at Miami of Ohio, I also benefited from the sage influence of Peter Williams and Jim Hanges. The project took on new directions and layers in my PhD work at Northwestern University. There George Bond, my adviser, aided me with gentle, humble guidance while Stuart Sarbacker and Wendy Doniger of the University of Chicago enlivened my outlook with thoughts on how the wider Indian religious landscape could play into my research. Robert Launay and Sarah McFarland-Taylor pushed me to sharpen and refine my theoretical approach, helping me to grow as a scholar. My fellow PhD comradesTobin Miller-Shearer, Amanda Baugh, Shuman Chen, Kristin Doll, and Hayley Glaholtprovided moral support along the way. At my first academic appointment as a Post-Doctoral Fellow at Ripon College, Brian Smith motivated me to think in more expansive ways about what a book based on my prior graduate research might look like. During the same period, Brian Black and Laurie Patton introduced me to a wider circle of scholars with overlapping interests in the dialogic nature of Asian religious narratives. Faculty at Saint Josephs College provided me with great support as I worked on the final research and writing that became this book. Mike Malone, Rob Reuter, and Maia Hawthorne served as wonderful conversation partners for considering the philosophical and literary aspects of the work. Carla Luzadder in the Robinson Memorial Library assisted me in procuring needed texts, as obscure as they were at times. During the last few years, the friendship and support of Tom Ryan and Chad Pulver were especially critical. Closer to home, Ron and Carol Jaskula (my mother- and father-in-law) have cheered me on throughout my studies and have been exceedingly generous with their help, whether it was childcare, household repairs, or putting me up as a boarder so I could take classes in Sanskrit. My mother and father, who raised me to delight in questions, stories, and the mysteries of the world, deserve more thanks than I can ever provide, helping to support me and my family during the lean years of graduate school and beyond. It is more than I can ever repay. When my wife and I started our family during my PhD studies, I could not anticipate the early mornings or the late nights, while I tried to write at the computer, of stopping what I was doing to help usher one or the other little boy back to sleep. Over the years, though, as our children, Xander and Luka, have grown in their own love of learning and stories, they even at times have taken inon occasion even asking for!lectures on Buddhism, Indian literature, or monsters. Their curiosity is an ever-enriching fountain. The one I must thank the most, though, is my wonderful wife, Jeanette. When we first met, our hours- and night-long conversations took my breath away, and this is still the case decades later. You have opened my eyes to ways of knowing and thinking that I would not have imagined. Your intellectual curiosity inspires me and your love sustains me. I could accomplish nothing without you.

Abbreviations

Frequently cited Buddhist and Hindu texts are abbreviated in the manuscript notes as follows:

AN | Anguttara Nikya |

BC | Buddhacarita |

DN | Dgha Nikya |

K.Up. | Kaha Upaniad |

LV | Lalitavistara |

MB | Mahbhrata |

MN | Majjhima Nikya |

MV | Mahvastu |

NK | Nidnakath |

RV | Rig Veda |

SN | Sayutta Nikya |

Sn | Sutta Nipta |

Mapping out Mra

Who is Mra?

An early Buddhist Pli text describes an encounter between the Buddha and a being named Mra. This Mra, attempting to assert his power over the Buddha as well as to frighten him, makes the following declaration:

The eye is mine, ascetic, forms are mine the ear is mine, ascetic, sounds are mine the nose is mine, ascetic, odors are mine the tongue is mine, ascetic, tastes are mine the body is mine, ascetic, tactile objects are mine the mind is mine, ascetic, mental phenomena are mine Where can you go, ascetic, to escape from me?

This provocative, even chilling passage immediately prompts several questions. Who is this Mra? What is he after? How could he be so confident in his assertion of power and control over someone like the Buddha, someone who almost all other characters in these Buddhist texts and stories seem to revere?