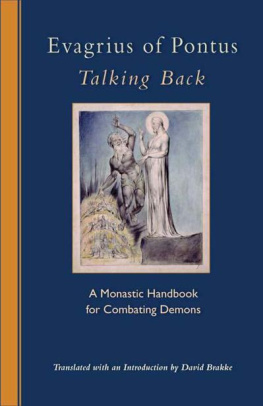

Evagrius of Pontus

Talking Back

CISTERCIAN STUDIES SERIES NUMBER TWO HUNDRED TWENTY-NINE

Evagrius of Pontus

Talking Back

A Monastic Handbook for

Combating Demons

Translated with an Introduction by

David Brakke

A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press

Cistercian Publications

Editorial Offices

Abbey of Gethsemani

3642 Monks Road

Trappist, Kentucky 40051

www.cistercianpublications.org

Evagrius of Pontus, Saint, c. 345399

Talking Back translated from the edition of

Wilhelm Frankenberg

Euagrios Ponticus

Abhandlungen der kniglichen Gesellschaft der

Wissenschaften zu Gttingen,

Philologisch-historische Klasse, Neue Folge 13.2

Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1912

New Testament quotations are from New Revised Standard Version Bible , copyright 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

2009 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint Johns Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Evagrius, Ponticus, 345?399.

[Antirrhetikos. English]

Talking back : a monastic handbook for combating demons / Evagrius of Pontus ; translated with an Introduction by David Brakke.

p. cm. (Cistercian studies series ; no. 229)

In English, translated from a Syriac translation of the Greek original.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes.

ISBN 978-0-87907-329-9 (pbk.)

Ebook ISBN 978-0-87907-968-0

1. Spiritual warfare. I. Brakke, David. II. Title. III. Series.

BV4509.5.E82513 2009

248.8'942dc22

2009004768

To Mary Jo Weaver

experienced in the movements of the soul and the ways of prayer

Contents

Acknowledgments

I completed a rough translation of Talking Back while I was an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow at the Institut fr gyptologie und Koptologie of the Westflische Wilhelms-Universitt Mnster. I am grateful to the Humboldt-Stiftung for its generosity and to my host, Stephen Emmel, for his hospitality and support. William Harmless encouraged me to undertake this project and responded to an early portion of my translation. Robert Sinkewicz offered sage advice and generously shared with me his own working translation of Talking Back . Kevin Jaques lent me his expertise in Arabic as I studied Loukioss letter to Evagrius. Rowan Greer read a draft of the entire book and made several important suggestions and corrections, and Mary Jo Weaver did the same for the Introduction. A group of students in Syriac at Indiana University read portions of the text with me. I have presented the ideas found in the Introduction to several audiences, who responded with helpful questions and comments, especially at the North American Patris tics Society, the History of the Book Seminar at Indiana University, and the Fifteenth International Conference on Patristic Studies (2007) at the University of Oxford. E. Rozanne Elder of Cistercian Publications greeted my project with enthusiasm and patience, and the anonymous readers provided welcome endorsements of my efforts. Father Mark Scott of Cistercian Publications and Colleen Stiller of Liturgical Press and her staff produced this book with intelligence and care. As always, Bert Harrill has provided me with endless moral support. I am grateful to all of these persons and institutions; the shortcomings of this work are my own.

Portions of the Introduction repeat material from my Demons and the Making of the Monk: Spiritual Combat in Early Christianity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006).

Introduction

Sometime in the final decade of the fourth century, a monk named Loukios wrote to Evagrius of Pontus, one of the leading spiritual guides among the monks of the Egyptian desert. Calling him honored father, Loukios asked Evagrius to compose for him a treatise that would explain the tactics of the demons that try to undermine the monastic life; Loukios hoped that such a work would help him and others to resist more successfully the evil suggestions that the demons made. In response, Evagrius sent Loukios a letter, now known as his fourth, and a copy of the work translated here: Antirrhtikos , or Talking Back . Among the monks of late antiquity and early Byzantium, it became one of the most popular of Evagriuss books: ancient authors regularly mentioned it in their discussions of Evagrius, and it was eventually translated from the original Greek into Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, and even Sogdian.

Talking Back has not enjoyed the same level of popularity among modern students of early Christian monasticism. One reason for this neglect is linguistic: both the Greek original and the Latin translation are lost; complete texts survive only in Armenian and Syriac manuscripts that are either not fully edited or difficult to access. But also Talking Back concerns itself exclusively with the monks combat with demons, a topic that has not interested many modern historians and theologians, most of whom have directed their attention to social and cultural features of early monasticism or to aspects of monastic spirituality that appear more directly relevant to contemporary persons, such as prayer or spiritual direction. Intense conflict with demons, however, especially in the form of thoughts, lay at the heart of the early Egyptian monks struggle for virtue, purity of heart, and thus for salvation. Opposition from demons, whether they tempted the monk to sin or tried to frighten him into abandoning the ascetic life, provided the resistance that the monk needed to form himself into a person of integrity. In Talking Back we find the thoughts, circumstances, and anxieties with which the demons assailed the monk, and we observe a primary strategy in the struggle to overcome such assaults: antirrhsis , the speaking of relevant passages from the Bible that would contradict or, as Evagrius puts it, cut off the demonic suggestions.

Evagrius of Pontus crafted the most sophisticated demonology to emerge from early Christian monasticism and perhaps from ancient Christianity as a whole. Born around 345 to a country bishop in the region of Pontus in Asia Minor, Evagrius showed religious and intellectual promise even as a teenager and was ordained a reader by Bishop Basil of Caesarea. He then became the protg of Gregory of Nazianzus, serving as Gregorys archdeacon when he became bishop of Constantinople in the late 370s and assisting him in his efforts in behalf of Nicene theology. It is tradi tional to believe that Evagrius received his grounding in an Origenist Christian theology under Gregory and subsequently learned about ascetic practice and demonic conflict from monks in Egypt, but we shall see below that there is evidence that even Gregory may have contributed to his knowledge of the demons and of strategies against them. In any event, Evagriuss discipleship under Gregory came to an end when Gregory had to resign his episcopal seat and Evagrius fled to Jerusalem after he fell in love with a married woman.

In Jerusalem Evagrius suffered an emotional and physical breakdown, and the ascetic leader Melania the Elder persuaded him to take up the monastic life in Egypt. In the deserts of Nitria and Kellia, Evagrius apprenticed himself to monks such as Ammonius and the two MacariiMacarius the Great (or the Egyptian) and Macarius the Alexandrianfrom whom he must have received much of his advanced knowledge about demons and combat with them. Evagrius soon emerged as an authoritative teacher in his own right, and around him gathered a group of monks that at least one contemporary author called the circle around Evagrius. Supporting himself as a calligrapher, Evagrius counseled the monks who visited him and with whom he gathered weekly for worship and fellowship, and he produced a large number of literary works of great variety, not only practical treatises on the monastic life, but also works of biblical exegesis and of advanced theology. Even these latter works, however, support Evagriuss vision of monasticism in which bodily discipline, demonic conflict, prayer and psalmody, biblical study, and speculation on higher theological questions all played important roles in forming the monk into a gnostic, a knower of God. Talking Back may be focused on the very practical problem of resisting demonic suggestions, but the scope and precision of both its atten tion to the monks soul and its treatment of the Bible reveal the creativity and intelligence of a great theologian.