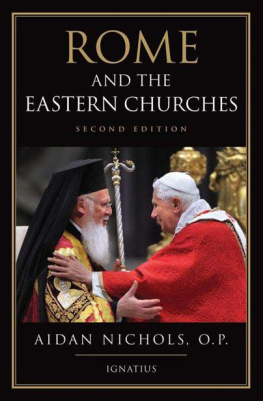

ROME AND THE EASTERN CHURCHES

Aidan Nichols, O.P.

ROME AND THE

EASTERN CHURCHES

A Study in Schism

Revised edition

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

First edition:

1992 by T & T Clark

Edinburgh, Scotland

Published in the U.S. in 1992

by Liturgical Press

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations (except those within

citations) have been taken from the Revised Standard Version of the

Holy Bible, Second Catholic Edition, 2006. The Revised Standard

Version of the Holy Bible: the Old Testament, 1952, 2006; the

Apocrypha, 1957, 2006; the New Testament, 1946, 2006; the

Catholic Edition of the Old Testament, incorporating the Apocrypha,

1966; the Catholic Edition of the New Testament, 1965, 2006, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the

Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved.

Photograph by Stefano Spaziani

Pope Benedict XVI with Patriarch Bartholomew I

(Archbishop of Constantinople and Ecumenical Patriarch)

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

Second edition

2010 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-282-4

Library of Congress Control Number 2009934934

Printed in the United States of America

To the honoured memory of

Adrian Fortescue

(1874-1923)

priest, Orientalist, liturgist

luminary of the English Catholic Church

Now Bethsaida may rejoice

for in thee, as from a mystical pot ,

flowered forth most sweet-smelling lilies ,

Peter and Andrew .

Greek Menologion for the Feast of Saint Andrew,

30 November

Contents

4. The Estrangement between Rome and Constantinople,

I: General Trends

5. The Estrangement between Rome and Constantinople,

II: The Rle of the Emperor

6. The Estrangement between Rome and Constantinople,

III: The Growth of the Papal Claims

Preface to the

First Edition (1992 )

The present study of relations between the Papacy and the churches of the East appears at a crucial time for the fate of the Great Church: historic Christendom. On the one hand, the internal difficulties of Western Catholicism are acutely apparent even to readers of the secularnever mind the religiouspress, where reports of theological dissidence and revolt against the authority of Rome appear monthly if not weekly. Arising from a variety of immediate issuesliberation theology (the Americas, India, the Philippines), black theology and ecology (the United States), feminism and sexual ethics (the Anglo-Saxon world generally, Western Europe), inculturation and the possibilities of assimilating non-Christian religiosities (India, sub-Saharan Africa), and the use to be made of contemporary biblical exegesis (academe berhaupt )such movements manifest themselves not only in continuing liturgical experimentation with the already mauled and suffering Roman rite, but, even more characteristically, in criticism of the see of Rome. Ranging in tenor from the courteous to the caterwaul, this criticism touches not only the policies and the power of the Papacy, but the context of those policies and the grounding of that power, namely, the fundamental position of Rome within the communion of churches which is Catholicism worldwide. It may be offered in the name of: a more effective co-governance of the Church by college of bishops and Pope; the rights of local, or national, churches; a synodal structure of Church government with roles for laity and lower clergy as well as bishops; or a democratic populism of the base church. Such critiques sometimes include reference to the doctrinal, and practical, posture taken up historically by the (separated) Eastern churches, insinuating or insisting, that the contemporary desire of Western Catholic liberals and radicals to cut the Papacy down to size is but the continuation of the (legitimate) fraternal correction offered by the Christian East to a Roman bishop tempted by the memory of his Petrine prerogatives to occupy the position of a super-pope.

On the other hand, those Orthodox (and other Oriental) Christians who are most au fait with the present situation of Western Catholicism are all too aware that, in the dynamic of forces now at play in the Latin church, assault on Rome becomes only too easily a sorcerers apprentice, whose unstoppable sea of reform will wash away not only certain encrustations of papal practice but (humanly speaking) the apostolic tradition itself. For at the heart of many (but not all) of the centrifugal movements in modern Western Catholicism lies a common canker: the loss of a sense for the objective, supernatural Christian revelation given in history, and passed down by the apostolic Church, in the combined media of her liturgies, her doctrinal teaching, and her life. As Father Avery Dulles, of the Society of Jesus, recently wrote, divorced from this matrix, much contemporary theology runs the risk of turning into a rootless philosophy of religion, or into social commentary. In recording the comments of these two writers, some allowance must be made for a North American standpoint; yet it will not do, as some voices in the Roman Curia seem occasionally to urge, to blame all the ills of the Catholic Church today on the deficiencies of American culture.

The present conjuncture necessarily lends a new ambivalence to any study of the relations of Rome with the Eastern churchesyet it also gives that study a new urgency. One strategy open to Rome is, evidently, to call up from the vasty deep the spirits of the Christian Eastfor in the struggle for the conservation of a classical understanding of doctrine, liturgy, spirituality, ethics, and (for the most part) Church government, the East can stand with Rome over against Neo-Modernist, or Neo-Protestant, tendencies in the West. The Orientalisation of Rome is already apparent, indeed, in such diverse media as the recent documents of the Roman Congregation for Catholic Education on the importance not only of a renewed study of the fathers but, more specifically, of the Christian East itself, in seminary formation in the Latin church, and the ethos of the draft Universal Catechism, many of whose citations are drawn from the Eastern fathers and liturgies.

In this process, the ecumenical dialogue with the Orthodox (and, to a lesser extent, the Oriental Orthodox) churches would seem an obvious contender for the role of a major supporting part. However, the liberation of the Byzantine-rite Catholic churches of Eastern Europe, in the course of the dramatic events in the USSR and elsewhere in 1989, andto a less marked degreethe renaissance of the Syrian-rite Catholic church in India has complicated the ecumenical aspect. The recognition by Rome of the Uniate churches of the Ukraine and Romania (in particular) has dismayed, and even angered, many Orthodox, and this at a time when the dialogue of the (Chalcedonian) Eastern Orthodox with the (Non-Chalcedonian) Oriental Orthodox (Monophysite) churches is moving ahead with great gusto. The high wire which the Holy See is dangerously trying to walk consists in, on the one hand, giving support and sustenance to the Oriental Catholic churches, while, on the other, maintaining the full momentum of the dialogue with the separated Eastern churches in whose eyes Uniates are, if not an abomination, then at least an obstacle. The suffering of the Uniates in the cause of communion with Rome could be neglected by Rome only at the cost of an undesirable reputation for supine ingratitude, as well as a suspicion of failing confidence in her own special claims. And yet the wider rewards of reunion with the Orthodox (and to a lesser extent Oriental Orthodox) East would be, if harvested, more substantialnot only thanks to the presence of a large Orthodox diaspora in those countries (North America, Australia, Western Europe) where theological liberalism is at its most rife, but also given what could be expected of such self-confident churches as those of Greece and Russia in their contribution to a catholicity of which Rome would be the first see.

Next page