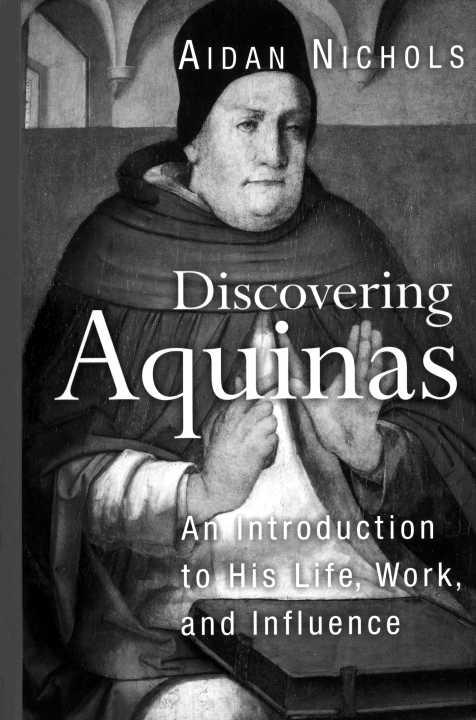

Discovering Aquinas

Discovering Aquinas

An Introduction to His Life,

Work, and Influence

Aidan Nichols op

Contents

vii

Part One: The Man

Part Two: The Doctrine

Part Three: The Aftermath

Part Four: The Tools

Preface

In John Gray's novel Park, set centuries hence, Dlar shows his visitors an item of furniture of outstanding beauty:

See the best of all, as to the embellishments; and with that he displayed the painted inside of the boards, in glowing opus lense, golden without the use of gold. Scenes from the Summa, said the giver, in reverent and delicate banter. Such indeed were the subjects; for there may be lovely and exquisite emblems of what is abstract.'

`Natural forms', writes Thomas in the De veritate (the `disputed questions about truth'), `are as it were images of immaterial realities'.' Brought into play re-wrought as symbols, they can stand for deep or complex concepts.

A theological thinker for whom that is a congenial reflection is useful to those of us who need the help of the poet's sensibility if we are to be awoken from the prose of our metaphysical slumbers. Certainly, there is a difference of intellectual temper between those who approach the topic of theology with a robust assurance of the power of philosophical argument and those others, more affected by images than by ideas, who look to history and experience for the presentation of religious theory. (Immanuel Kant would call the contrast one of Verstand with Vernunft, but centuries earlier Thomas had spoken of intellectus and ratio.) It is easy for the supporters of either to make a caricature of the other. And yet they are, or can be, complementary. It is in the spirit of Thomas - who approved of distinctions but disliked the `either/or' - to follow up both approaches. Though at one point criticising Plato for `proposing everything in figures and by the art of symbols', a selection of images is vital to Thomas - who was both a conceptual thinker and a poet - in the setting forth of sacred truth.]

I like to think of this as Thomistic interpretation `in the English manner'. I have suggested elsewhere that the particular contribution of the English Dominicans of a pre-Conciliar generation to the Thomist patrimony lay in the furnishing of a powerfully incarnational idiom for its articulation.' In this they belonged to a wider common tradition. Religious metaphysics, whether Catholic or Anglican, in modern England - in Hopkins and Chesterton, Lewis and Sayers, Farrer and Mascall - delights to put ideas and images together in words, not to keep them apart. There is, I hope, a touch of this in what follows.

It is far from irrelevant to the historical St Thomas: the one who actually lived. His prose may not seem especially imagistic. It is far more so than some Thomistic manuals would suggest. In the course of giving a brief answer to a couple of objections to some thesis, Thomas is perfectly capable of switching from the most austere metaphysical analysis to some extravagant metaphor taken from a Greek Father or a Carolingian monk. But more to the point is the whole texture of his thought. In his commentary on The Divine Names, a treatise of fundamental theology by the sixth-century Syrian monk who used the pseudonym of `Denys the Areopagite', Thomas remarks:

We do not know God by seeing his essence, but we know him from the order of the whole universe. For the very `university' of creatures is proposed to us by God so that through it we may know God insofar as the ordered universe has certain imperfect images and assimilations of divine [things], which are compared to them as exemplary principles to images.'

This Christian-Platonist comment yields up a presupposition of Thomas's entire vision and warrants that kind of imaginative commentary on the severer conceptual reaches of his thought in which such English commentators on the angelic doctor as Thomas Gilby both delighted and excelled.6

A later generation of English Dominican writers were more restrained. Influenced by the predominantly logical and languageanalysis concerns of contemporary Anglo-American philosophy, Gilby's younger collaborators in the Cambridge bilingual Summa theologiae like Herbert McCabe, who died in 2001, or friars, like Brian Davies, of a later generation still, discussed (and discuss) Thomas in a way well suited to the Anglophone philosophical climate of our time.' In this modest introduction to the life and work of Aquinas, the present author, though conscious of debts to his brethren of the English Province (in particular, those of the preConciliar period), owes more to the French-language reception of Thomas in the twentieth century: notably, to the metaphysically and dogmatically meaty studies of Thomas's thought produced by the Dominicans in France." Some acquaintance with the flourishing garden of American Thomistic scholarship is also exhibited in these pages.

At certain points, where it seemed illuminating, or, from the standpoint of the good of the Catholic intellectual tradition, pastorally pressing, I have also tried to bring Thomas's thought into critical correlation with theological predecessors and successors - some of a very different ilk, in our own day. The `line' taken is that Thomas constitutes the classic theological moment of Latin Christendom. This is not only because he had a pre-eminent gift of synthesising the materials of Scripture and patristic Tradition, revelation's witnesses. It is also because he honed a metaphysic that was up to the job of being that revelation's philosophical instrument - in the traditional language, its serviceable `handmaid'. It is hardly surprising, then, that any major derogation from Thomas's achievement (to be carefully distinguished from enrichment of it by the provision of complementary insights) will tend to create difficulties for the articulation of Catholic faith.

I began this Preface with a citation from John Gray that considers how Thomas's work might be reflected in the visual arts. Christian iconographers have from time to time fashioned `lovely and exquisite emblems' for the picturing of Thomas himself, in an effort to make manifest what his oeuvre signifies for the Catholic interpretation of the Gospel. Shortly after the middle of the fourteenth century, Tommaso da Modena painted the chapter room of the priory of St Nicholas at Treviso with a number of frescoes of Dominican saints and scholars. Thomas is shown standing before a desk at a lecturer's chair. In his right hand he holds the book of Scripture while his left hand rests on a tiny church onto, and into, which rays of light are streaming from a sun gleaming on his breast. Here is Aquinas diffusing light for the Church - the Church on which, however, he in turn depends.' The burning sun emblemises (John Gray's word!) Thomas's teaching that theology, unlike other sciences, being as it is a knowledge of the divine mysteries seen from the viewpoint of divine Wisdom herself -'a certain impression of the divine knowledge"0 - requires an ascetic and spiritual effort of purification, at once affective and intellectual. Hence the need in the theologian's life for charity, the supreme evangelical virtue, and the Gifts of the Holy Spirit, those ways in which human powers become more finely attuned to divine leading."