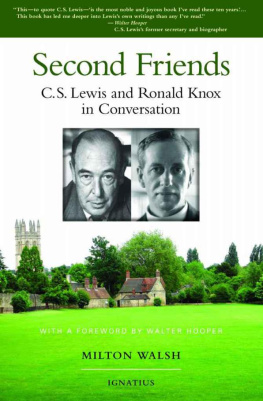

SECOND FRIENDS

FATHER MILTON T. WALSH

Second Friends

C.S. Lewis and Ronald Knox in Conversation

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover photograph of C.S. Lewis

Used by permission of The Marion E. Wade Center,

Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois

Cover photograph of Ronald A. Knox

Used by permission of

National Portrait Gallery, London

Background photograph of Oxford iStockphoto

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

2008 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-240-4

Library of Congress Control Number 2007938142

Printed in the United States of America

To my brother priests,

first friends and second friends

in the Vineyard of the Lord,

and

with special gratitude to

Monsignor Cornelius J. Burns

(1929-1995)

who so generously shared with me

his love for the great English convert authors

He followed the truth... It was a wine he thirsted for, he was love-sick for its romance... a man who lived haunted by the truth, and died desiring it .

Ronald Knox

The Conversion of Newman

Occasional Sermons

Contents

Foreword

Thisto quote C.S. Lewisis the most noble and joyous book Ive read these ten years. It is also one of the most surprising. After immersing myself in the writings of Lewis for half a century I could not, when I first heard Milton Walsh talk about the book, see how C.S. Lewis and Ronald Knox could benefit from being placed together. I am now totally converted. This book had led me deeper into Lewis own writings than any Ive read.

I share Fr. Walshs regret that Lewis and Knox did not get to know one another better. But there are reasons for this. Fr. Knox was the Catholic Chaplain to Oxford University between 1926 and 1939, shortly before Lewis was converted in 1931 and about the same time Lewis was writing his first theological book, The Problem of Pain (1940). Perhaps if Knox had been in Oxford during the time Lewis was writing theology they might have come to know one another well. I think Fr. Knox is one of those Lewis would have asked to advise him on the series of radio talks that became Mere Christianity (1952).

This is certainly suggested by the delight they took in one another on the occasion that their mutual friend Dr. Havard brought them together, and whenas Fr. Walsh tells usLewis greeted Knox as possibly the wittiest man in Europe.

It was a promising beginning. But if Knox had remained in Oxford I expect he would have noticed that Lewis was to a large extent trapped by his success as an apologist. Having found himself such a successful defender of Mere Christianity Lewis worried about what would happen to his readers if he discussed things specifically Catholic. There is also the fact that, much as he loved rational opposition, Lewis was shy of addressing what he called real theologians, and this would have included Catholic priests of such eminence as Monsignor Knox.

But enough conjecture. What I most love about this book is that Milton Walsh, after admitting that it is a pity they did not get to know one another better, gets on with a job so worthwhile you end up wondering if it made much difference whether Lewis and Knox were close personal friends or not. The important thing, as the author says in the Introduction, is that both men were apostles who cared passionately about what they believed. Or as Lewis pointed out in the chapter on Friendship in The Four Loves (1960), it is when two people see the same truth that Friendship is born.

In that same chapter Lewis pointed out that Friendship is always about something, and there were perhaps few people living at the time who cared more than Lewis and Knox about making the Gospel known. Milton Walsh is an encyclopedia of the ideas Knox and Lewis wrote about, and by laying their thoughts side by side like railway tracks their separate apologetics influence one another and together constitute a powerful case for Christianityin some ways more powerful than if read separately. The instance which moved me most was their joint work on Miracles in Chapter Four. My debt to Lewis is so enormous that it is not easy for me even to imagine how anyone could improve his effectiveness in writing about that subject. But I did not know that Knox had already addressed the question in Some Loose Stones (1913). Lewis came along and built on an edifice Knox had prepared.

I concede that the case for Miracles, when Fr. Walsh has these like-minded contemporaries, these Second Friends, working in tandem, is one of many instances in which the case for Miracles is made not twice as strong, but many times stronger. They worked in tandem, not because their thoughts were identical, but because there were no two contemporaries writing at the time who complemented one the other so perfectly.

Why did no one think of putting them together before? I think I know the answer. Milton Walsh is young enough to be the grandson of Lewis and Knox, but he is so effective in getting into the skins on those men that one could easily mistake him for their contemporary.

INTRODUCTION

Second Friends?

On most afternoons in the 1930s, two of the most popular Christian writers in England took a daily walk through the meadows of Oxford. They did not walk together: C. S. Lewis ambled along Addisons Walk near Magdalen College, while Ronald Knox strolled around neighboring Christ Church Meadow. They enjoyed talking with friends during these outings. It was on Addisons Walk that J. R. R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson first suggested to Lewis the idea that Christianity could be viewed as a myth that happened to be historically true, an idea that was instrumental in his Christian conversion. As for Ronald Knox, he once confided to his friend Dom Hubert van Zeller that his idea of a perfect vacation would be to take his daily walk in Christ Church Meadow discussing the nature of God with his Jesuit friend, Father Martin DArcy. (Dom Hubert admitted candidly that this was certainly not his idea of a jolly summer holiday!)

Late in the 1930s, Doctor Humphrey Havard invited Knox and Lewis to lunch, and the two men had a most enjoyable afternoon. Many years later Havard recalled the occasion:

Lewis started well by greeting him [Knox] as possibly the wittiest man in Europe. After that the party flourished, and both afterward expressed their delight with the other. Each was witty, humorous, and very widely read; each had an unobtrusive but profound Christian faith. They had much to say to each other, and it was a pity that Monsignor Knox left Oxford and that they had few further opportunities to meet. Each of them later told me of their admiration and liking for each other.

Had Knox stayed in Oxford, might he and Lewis have become friends? If so, they would have been what Lewis called Second Friends. Lewis once described Arthur Greeves as his First Friend and Owen Barfield as his Second Friend. What was the difference? He said a First Friend shares all your interests and most secret delights and sees the world as you do: he and you join like raindrops on a window. The discussions and arguments provide a seedbed for affection. Lewis was blessed with many Second Friends, and their good-natured but deadly serious debates bore fruit in the remarkable writings of the Inklings.

Knox was not a member of this illustrious circle, but he and Lewis had much in common. They were at home in the world of Oxford and enjoyed the debates and enterprises of academic life. Neither went abroad very often, and they had a passion for trains when traveling around Britain. As young men, both Knox and Lewis had been stylish in their dress, but in later life they were deliberately unconcerned about such things. Politics did not loom large: they bought the Times primarily for its crossword puzzle. They were much sought after as speakers, and they each had an unaffected delivery, reading from a typescript in a reserved yet decisive manner. They wore their accomplishments lightly, and even people who hardly knew them referred to them as Ronnie and Jack (a nickname Lewis devised for himself as a child).

Next page