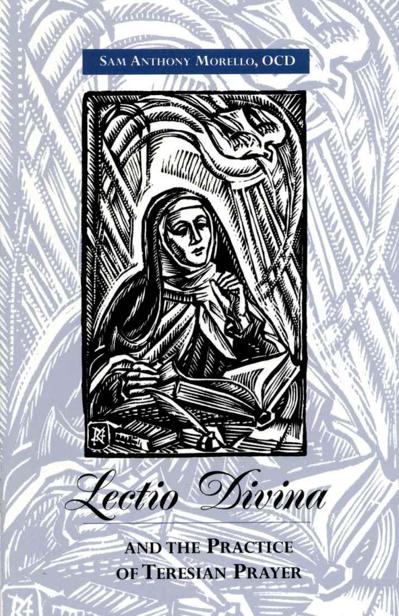

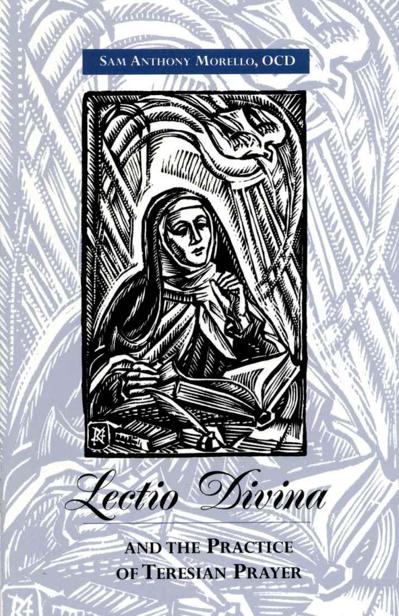

Lectio Divina

and the

Practice of Teresian Prayer

Sam Anthony Morello, OCD

An ICS Pamphlet

ICS Publications

Institute of Carmelite Studies

Washington, D.C.

1995

Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, Inc. 1994

(This article originally appeared in the Summer 1991 issue of Spiritual Life .)

ICS Publications

2131 Lincoln Road NE

Washington, DC 20002-1199

Typeset and produced in the U.S.A.

Cover Woodcut by Robert F. McGovern

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morello, Sam Anthony, 1934-.

Lectio divina and the practice of Teresian prayer /

Sam Anthony Morello

p. cm. -- (An ICS pamphlet)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 0-935216-24-3

1. Prayer--Catholic Church. 2. Teresa of Avila, Saint, 1515-1582.

3. Carmelites--Spiritual life. 4. Bible--Devotional Use.

I. Title. II. Title: Lectio divina. III. Series.

BV215.M7 1994

242'.802--dc20 94-28368

CIP

Contents

About the Author

Sam Anthony Morello, OCD, is a priest of the Southwestern (St. Thrse) Province of Discalced Carmelites, where he has served as novice master, student master, provincial councilor, provincial delegate to the Secular Carmelites, and Director of the Mt. Carmel Center in Dallas, Texas. In 1991 he completed a term as Definitor (Councilor) at the Discalced Carmelite Generalate in Rome, Italy.

Abbreviations

All quotations from St. Teresa of Jesus are taken from The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Avila , trans. Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez, 3 vols. (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1976-1985). For her major works, the following abbreviations are used:

Castle = Interior Castle

Foundations = Book of Foundations

Life = Book of Her Life

Way = Way of Perfection

The two numbers ordinarily following references to the Foundations, Life , and Way refer to the chapter and section in the ICS editions. Since the Interior Castle is divided into seven "dwelling places," references to the Castle include an additional first number, identifying the "dwelling places" in which a chapter and section may be found. Thus " Life , 8, 5" refers to the fifth section of the eighth chapter of the Book of Her Life , while " Castle , 6, 7, 10" refers to the sixth "dwelling places," chapter 7, section 10.

Lectio Divina

and the

Practice of Teresian Prayer

By Sam Anthony Morello, OCD

Introduction

To approach the subject of Teresian prayer (that is, prayer after the pattern of St. Teresa of Avila) we need a broad perspective. This is necessary, although perhaps surprising, because there is no distinctively Teresian way to pray. There is not even a uniquely Carmelite way to pray. Carmels spirituality is rooted in the greater tradition of lectio divina (literally, "divine reading"), a particular way of reading and praying over the Scriptures. This is why we read at the very heart of the Carmelite Rule of St. Albert: "Each one of you is to stay in his own cell or nearby, pondering the Law of the Lord [i.e., sacred Scripture] day and night and keeping watch at his prayers unless attending to some other duty" ( Rule , no. 8).

Pondering sacred Scripture was the way the early monks, the desert fathers and mothers, and in fact the people of the bible, prayed. And the monks developed a traditional method for doing that, the ingredients of which we find rehearsed in John of the Cross when he writes: "Seek in reading and you will find in meditatio n; knock in prayer and it will be opened to you in contemplation " ( Sayings , #158).

We will see how those four elements of lectio perfectly serve Teresian prayer, or better said, how the Teresian approach to prayer serves lectio . But let us first examine some underlying Teresian notions and principles, looking at Teresas methods and her preferred prayer orientation, as well as her understanding of the goals of prayer. All of these might be called Teresian "attitudes," wonderfully helpful attitudes that enrich the monastic tradition of prayer and can broaden contemporary approaches to prayer.

Teresian Notions

Mental Prayer . Teresas understanding of prayer is a good place to begin. We may simply recall what she says about prayer in chapter eight of her autobiography: "Mental prayer in my opinion is nothing else than an intimate sharing between friends; it means taking time frequently to be alone with him who we know loves us" ( Life , 8,5). This puts prayer in the category of friendship. Clearly, it is God who has initiated the friendship; thus personal prayer is a response to a love already shown us by the God of revelation. One goes to prayer as to someone whose love for us is assured; the one praying answers the voice of benevolence and love in return. This implies that prayer is an art to be cultivated, for it requires often setting time aside to attend to the friend. As we shall see, the friend is Jesus Christ, the center of the entire Teresian system.

The notion of prayer as a response to friendship gratuitously offered us by God through Christ is rooted in St. Johns Gospel. It is important, as John teaches, that we not pray to win Gods favor and love; God has already loved us most personally in Christ. What we need to do is answer that love. Thus prayer is an aspect of the life of grace. Graced prayer receives the love of God for the self and returns it in two ways: by loving God directly and by loving our brothers and sisters in God and for God. Prayer is "agape" received for personal transformation and then channeled back to God and out to neighbor. The very nature of evangelical and Teresian prayer spells out its goals. In sum, prayer is a loving exchange with Christ.

Vocal Prayer. Now let us see what Teresa means when she speaks of "vocal prayer." In a word, vocal prayer is nothing but formulary prayer, praying a pre-fabricated set of words and sentiments, like the "Our Father" or a psalm. The saint wants us to say our prayers well! She asks that we repeat the words "with understanding." She wants us to say our prayers "attentively." Reciting our vocal prayers well is already "mental prayer"; there is no distinction between mental and vocal prayer when vocal prayer is truly made ones own (see Way , 24). For Teresa the first lesson in learning to meditate is to say ones vocal prayers with attention and affection.

Meditation. It is helpful here to take a look at the term "meditation" in the Teresian writings. Teresa uses the word in reference to several prayerful activities that all qualify as ascetical prayer or "meditation." This is the first thing to note, that "meditation" for Teresa is a category of prayer. It is the prayer of effort, effort to think about and love the Lord. Meditation is all prayer this side of contemplation; it is the prayer of the first three dwelling-places of the Interior Castle and of the first waters of the Life .

With that understood, let us look at some specific applications of the term "meditation" in the saints writings. At the outset of the Interior Castle we read that "the door to the castle is prayer and reflection" ( Castle , 1, 1, 7). Reflection is the first meaning of meditation for St. Teresa, and she gives many examples of "much discursive reflection with the intellect" (see Castle , 6, 7, 10). The use of the imagination, reasoning, and will at prayer are all discursive meditative activities.

It is also "meditation" to devoutly follow the prayer outline of a meditation book. "There are books in which the mysteries of the Lords life and passion are divided according to the days of the week, and there are meditations on judgment, hell, our nothingness, and the many things we owe God together with excellent doctrine and method concerning the beginning and the end of prayer" ( Way , 19, 1). Teresa is open to this reflective use of a planned meditation book for those who find it helpful.

Next page