Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright 2021 by Brant Pitre

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Image, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Image is a registered trademark and the I colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Imprimatur: +Most Reverend Shelton J. Fabre

Bishop of Houma-Thibodaux

Nihil Obstat: Rev. Joshua Rodrigue, STL

Censor Librorum

The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat or Imprimatur agree with the content, opinions, or statements expressed.

Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible ( RSV ), copyright 1946, 1952, and 1971 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Note: All emphasis in Scripture quotations is the authors, and most archaic English (thee, thou, thy, etc.) has been updated.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pitre, Brant James, author.

Title: Introduction to the spiritual life / Brant Pitre.

Description: First edition. | New York: Image, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012930 (print) | LCCN 2021012931 (ebook) ISBN 9780525572763 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525572770 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Spiritual lifeCatholic Church. | Spiritual formationCatholic Church.

Classification: LCC BX2350.3.P564 2021 (print) | LCC BX2350.3 (ebook) | DDC 248.4/82dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012930

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012931

Ebook ISBN9780525572770

crownpublishing.com

Book design by Virginia Norey, adapted for ebook

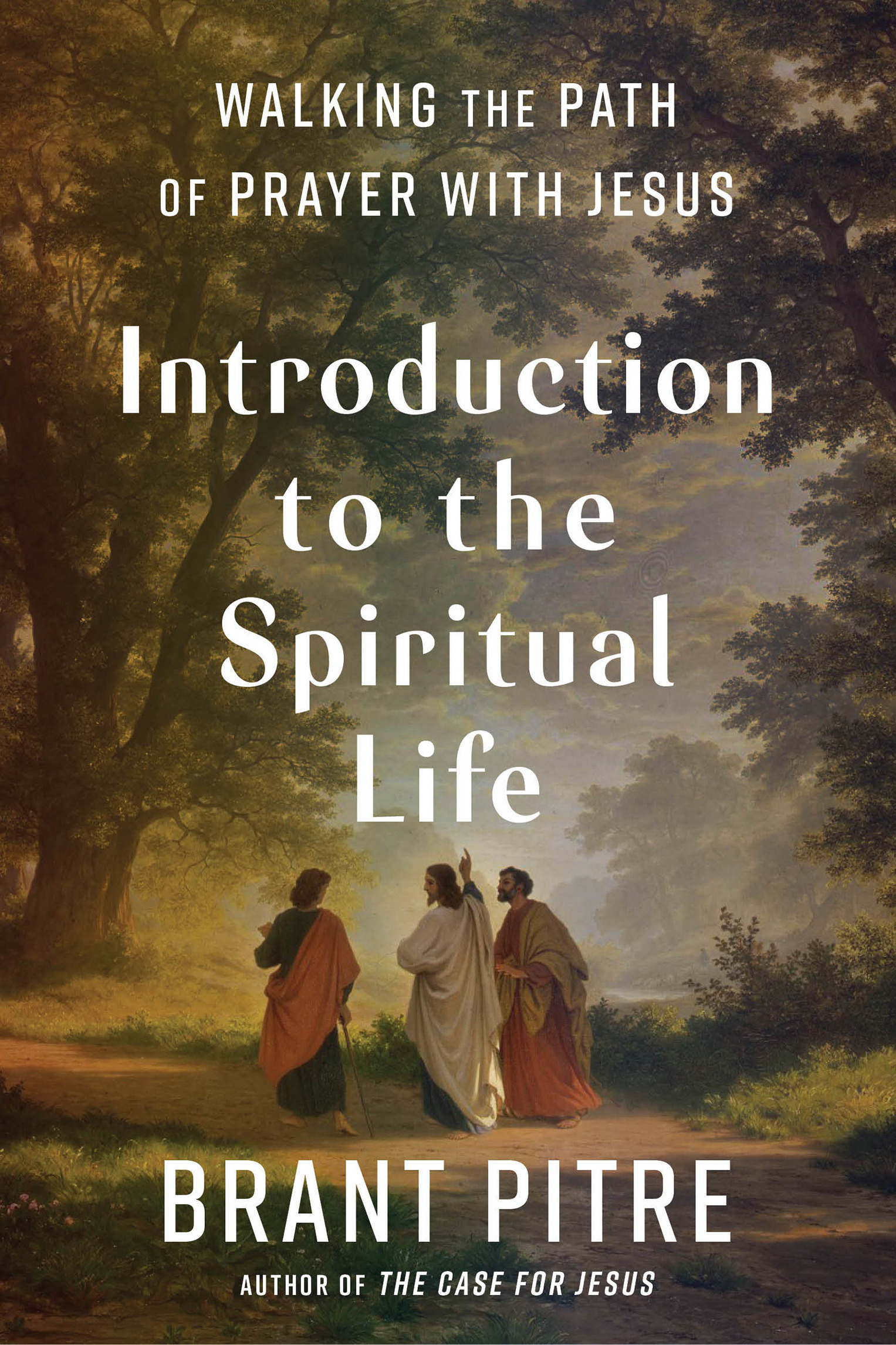

Cover art: Way to Emmaus by Robert Znd

ep_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

Contents

Introduction

If any one thirst, let him come to me and drink.

Jesus of Nazareth (John 7:37)

Many years ago, a friend offered to give me some free books from his personal theological library. At the time, I was a young professor with a new PhD and a mountain of student debt. Needless to say, I accepted. Little did I know that by some, he meant well over a thousand. In the end, he sent me over fifty large boxes, filled with books on the Old Testament, ancient Judaism, the New Testament, and early Christianityall topics I had studied during my doctoral program at the University of Notre Dame.

Several boxes, however, contained books on spiritual theologya subject about which I knew next to nothing. These included works by ancient Christian writers like John Cassian and John Climacus; medieval mystics like Catherine of Siena and Thomas Kempis; and modern spiritual masters like Ignatius of Loyola, Teresa of Avila, and John of the Cross.

Once I started reading the spiritual classics, I couldnt stop. It was like drinking water from a well after spending years in the desert. I began to learn for the first time about meditation, contemplation, the seven capital sins, their opposing virtues, and other topics. That year, when asked to teach an elective, I knew immediately it would be on spiritual theology. However, because my doctoral research was in biblical studies, I chose to focus on the scriptural roots of Christian spirituality.

To this day, that course remains the most powerful experience I have ever had in the classroom. During that time, I made several discoveries that ultimately laid the foundations for this book.

Three Kinds of Prayer

The first thing I learned was that there are different kinds of prayer. Growing up as a Catholic, I had always assumed that prayer simply involved saying the words of certain memorized prayers, like the Our Father. However, once I started reading the spiritual classics, I quickly discovered that the spiritual life involves much more. Although vocal prayer is essential, there are at least three major forms of prayer:

Vocal Prayer: praying with words, whether memorized or spontaneous.

Meditation: praying with the mind, especially by reading and reflecting on Scripture and entering into dialogue with God.

Contemplation: praying with the eyes of the heart, with a loving desire to see the face of God.

Each of these is deeply biblical. Jesus himself teaches his disciples a vocal prayer when he gives them the Lords Prayer (see Matthew 6:913). Likewise, the book of Psalms begins by blessing anyone who meditates on Scripture day and night (Psalm 1:12). Finally, the book of Exodus gives a classic description of contemplation when it describes Moses practice of praying in the Tabernacle. There the L ord used to speak to Moses face to face (Exodus 33:11). According to the spiritual classics, the life of every disciple of Jesus should involve all three kinds of prayer.

The Stages of Spiritual Growth

The second thing I discovered was that the spiritual life consists of certain stages of growth. When I was younger, I tended to think of my spiritual life as a kind of revolving door. On one side was deadly sin, or mortal sin. On the other side was repentance and forgiveness, or a state of grace. My primary aim was to die on the right side of the door! For many years, I felt like I was spiritually going in circles. I never had any sense of making progress. If anything, I felt like I was constantly backsliding.

To my surprise, this was not how the great spiritual writers describe the Christian life. Instead, just as a persons biological life ordinarily goes through certain stageschildhood, adolescence, and adulthoodso, too, a persons spiritual life normally goes through stages of growth. Over the centuries, these stages have been described by some spiritual writers as three ways or paths:

The Purgative Way: the path of spiritual childhood, focused on keeping the commandments, rooting out the capital sins (hence purgative), and learning to pray to the Father and practice meditation.

The Illuminative Way: the path of spiritual adolescence, focused on a deeper understanding of the mysteries of the life of Christ (hence illuminative), growing in virtues, and contemplation.

The Unitive Way: the path of spiritual adulthood, focused on union with God (hence unitive) through the power of the Holy Spirit and the perfection of faith, hope, and love.

Although this exact terminology took time to develop, the basic idea of three stages of spiritual growth is rooted in the Bible. For example, the apostle Paul contrasts spiritual children in Christ with those who have attained mature manhood (Ephesians 4:1314). Likewise, the apostle John distinguishes three spiritual ages in the Church: little children are the beginners, young men are those who have made spiritual progress, and fathers are the spiritual adults (1 John 2:1213).

Over the centuries, different spiritual writers have given a variety of names to these stages of the interior life. Nevertheless, the identification of three stagesthe beginning, the middle, and the endcan be found in ancient, medieval, and modern spiritual writers, in both Eastern and Western Christianity.