BENEDICT XVIS REFORM

The Liturgy between Innovation and Tradition

NICOLA BUX

BENEDICT XVIS

REFORM

The Liturgy between

Innovation and Tradition

Preface by Vittorio Messori

Translated by Joseph Trabbic

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Original Italian edition:

La riforma di Benedetto XVI

2008 by Edizioni Piemme Spa, Via Tiziano 32, 20145 Milan, Italy

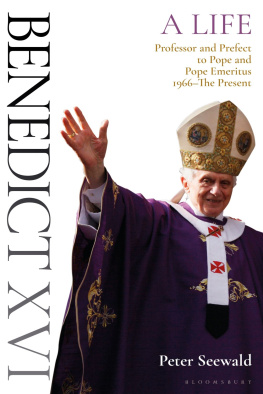

Front cover photograph:

Pope Benedict XVI

Stefano Spaziani

Cover designed by Roxanne Mei Lum

2012 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-446-0

Library of Congress Control Number 2011940706

Printed in the United States of America

TO THE DEAR MEMORY

OF FATHER ADRIANO GARUTI, O.F.M.

CONTENTS

The Liturgy: The Place Where God Meets Man

The Liturgy: Heaven on Earth

Rediscovering the Courage for the Sacred

Signs Evoke and Point to the Mystery

The Importance of Tradition

The Liturgy as Rule of Faith

Looking upon the Crucified Lord Orients Worship and the Heart

The Eucharist as Essence of Christian Worship

In Him We Have Been Made One

Christ Is the True Celebrant

The Liturgy Must Be Understood Again in Every Generation

The Reform Proposed by the Council and Its Implementation

Paul VIs Corrections

The Motu Proprios Key Doctrinal and Disciplinary Points

A Little History

Misinterpretations of the Papal Action

Ecclesial and Liturgical Continuity

The Missal of Pius V Was Not Abrogated

Two Theories Originating from Biblicism

The Priestly Service

The Participation of the Faithful

Looking upon the Cross

The Sacrality of the Church Building

Liturgical Formation

Translations and the Case of the Pro Multis

The Council, Latin, and Gregorian Chant

With the Patience of Love

PREFACE

The liturgical crisis that followed the Second Vatican Council caused a schism, with many excommunications latae sententiae ; it provoked unease, polemics, suspicions, and reciprocal accusations. And perhaps it was one of the factorsone, I say, not the onlythat brought about the hemorrhaging of practicing faithful, even of those who attended Mass only on the major feasts. Well, it might seem strange, but such a tempest has not diminished but, rather, increased my confidence in the Church.

I will try to explain what I mean, speaking in the first person, returning thus to a personal experience. Some would regard this approach as immodest, but others would see it as the simplest way of being clear and to the point. It happens to be the case that despite my age I have only a very slight recollection of the old form of the Churchs worship. I grew up in an agnostic household and was educated in secular schools; I discovered the gospeland began furtively to enter churches as a believer and no longer as a mere touristjust before the liturgical reform went into force, which for me meant only the Mass in Italian.

In sum, I caught the tail-end of history. Only a few months later, I would find the altars reversed and some new kitschy piece of junk made of aluminum or plastic brought in to replace the triumphalism of the old altars, often signed by masters, adorned with gold and precious marble. But already for some time I had seenwith surprise, in my neophyte innocenceguitars in the place of organs, the jeans of the assistant pastor showing underneath robes that were intended to give the appearance of poverty, social preaching, perhaps with some discussion, the abolition of what they called devotional accretions, such as making the Sign of the Cross with holy water, kneelers, candles, incense. I even witnessed the occasional disappearance of statues of popular saints; the confessionals, too, were removed, and some, as became the fashion, were transformed into liquor cabinets in designer houses.

Everything was done by clerics, who were incessantly talking about democracy in the Church, affirming that this was reclaimed by a People of God, whom no one, however, had bothered to consult. The people, you know, are sovereign; they must be respected, indeed, venerated, but only if they accept the views that are dictated by the political, social, or even religious ruling class. If they do not agree with those who have the power to determine the line to be taken, they must be reeducated according to the vision of the triumphant ideology of the moment. For me, who had just knocked at the door of the Church, gladly welcoming stabilitas which is so attractive and consoling to those who have known only the worlds precariousnessthat destruction of a patrimony of millennia took me by surprise and seemed to me more anachronistic than modern. It seemed to me that the priests were harming their own people, who, as far as I knew, had not asked for any of this, had not organized into committees for reform, had not signed petitions or blocked streets or railways to bring an end to Latin (a classist language, but only according to the intellectual demagogues) or to have the priest facing them the whole Mass or to have political chit-chat during the liturgy or to condemn pious practices as alienating, which instead were precious inasmuch as they were a bond with the older generation. There was a revolt on the part of certain groups of faithfulwho were immediately silenced, however, and treated by the Catholic media as incorrigibly nostalgic, perhaps a little fascistunited under the motto that came from France: on nous change la religion , they are changing our religion. In other words, although it was pushed by the champions of democracy, the liturgical reform (here I am abstracting from the content and am speaking only of the method) was not at all democratic. The faithful at that time were not consulted, and the faithful of the past were rejected. Is tradition not perhaps, as has been said, the democracy of the dead? Is tradition not letting our brothers who have preceded us speak?

Before judging its merits, let me repeat, it must be said that this reform came down from the clergy; the decision was handed down to the People of God from above, being thought out, realized, and imposed on those who had not asked for it or who had accepted it only reluctantly. There were some among the disoriented faithful who voted with their feet, that is to say, they decided to do other things on Sunday rather than attend a liturgy they felt was no longer theirs.

But, as a novice in Catholic matters, there was another reason for my stupor. Not having had particular religious interests previously, and being a stranger to the life of the Church, I knew that the Second Vatican Council was in progress from some newspaper headlines but did not bother to read the articles. So I knew nothing about the work and the long debates, with clashes between opposing schools, that led to Sacrosanctum concilium , the Constitution on the Liturgy, which was, among other things, the first document produced by those deliberations. Along with the other conciliar acts, I read the text afterward, when faith had suddenly irrupted into my life. I read it, and, as I said, I was left surprised: the revolution I saw in ecclesial practice did not seem to have much to do with the prudent reformism recommended by the Council fathers. I read such things as: Particular law remaining in force, the use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites; I found no recommendation to reverse the orientation of the altar; there was nothing to justify the iconoclasm of certain clergywhich was a boon for the antique shopswho sold off everything so as to make the churches as bare and unadorned as garages. It was the space for the participating assembly, for encounter and discussion, not for alienating worship orhorror of horrors!for an insult to the misery of the proletariat with its shining gold and art exhibits.

Next page

![Pope John XXIII - The Roman Missal [1962]](/uploads/posts/book/272720/thumbs/pope-john-xxiii-the-roman-missal-1962.jpg)