Contents

Page List

Guide

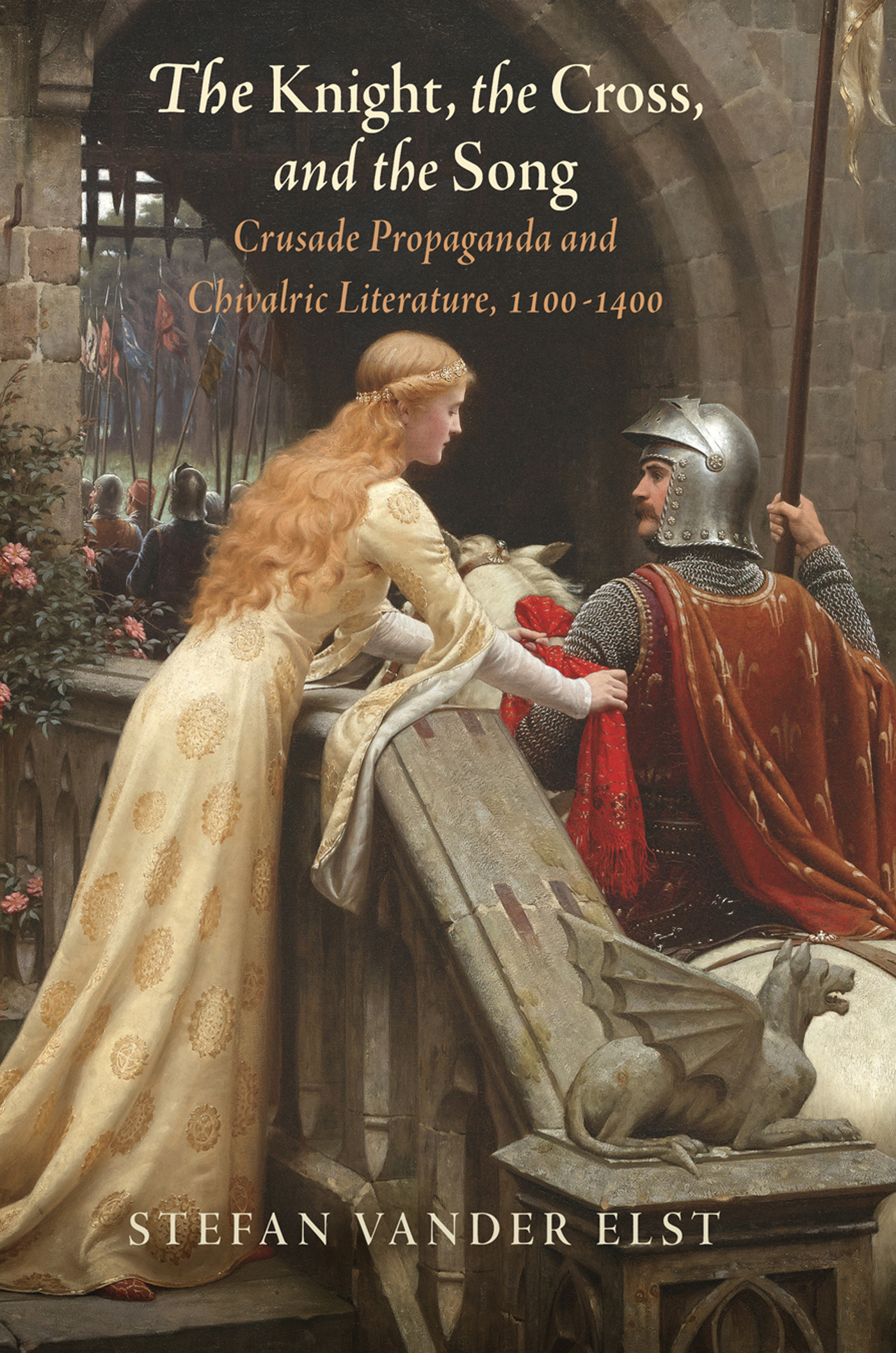

The Knight, the Cross, and the Song

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

RUTH MAZO KARRAS, SERIES EDITOR

EDWARD PETERS, FOUNDING EDITOR

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

The Knight, the Cross, and the Song

CRUSADE PROPAGANDA AND CHIVALRIC LITERATURE, 11001400

Stefan Vander Elst

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS Philadelphia

THIS BOOK IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A COLLABORATIVE GRANT

FROM THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION.

Copyright 2017 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4896-8

For Cynthia and Leo

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

BB | Cook, Robert Francis, ed. Le Btard de Bouillon: Chanson de geste. Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1972. Translation mine. |

BS | Boca, Louis N., ed. Li Romans de Bauduin de Sebourc, IIIe roy de Jhrusalem: Pome du XIVe sicle publi pour la premire fois daprs les manuscrits de la Bibliothque Nationale. 2 vols. Valenciennes: B. Henry, 1841. Translation mine. |

C | Myers, Geoffrey M., ed. The Old French Crusade Cycle. Vol. 5, Les Chtifs. University: University of Alabama Press, 1981. Translation mine. |

CA | Nelson, Jan A., ed. The Old French Crusade Cycle. Vol. 4, La Chanson dAntioche. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2003. Translation taken from Susan B. Edgington and Carol Sweetenham, trans. and eds. The Chanson dAntioche: An Old French Account of the First Crusade. Farnham: Ashgate, 2011. |

CCGB | Hippeau, C., ed. La Chanson du Chevalier au Cygne et de Godefroid de Bouillon. Paris: A. Aubry, 18741877. |

CJ | Thorp, Nigel R., ed. The Old French Crusade Cycle. Vol. 6, La Chanson de Jrusalem. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1992. Translation mine. |

CR | Bdier, Joseph, ed. La Chanson de Roland. Paris: Ldition dArt H. Piazza, 1960. Translation taken from Glyn S. Burgess, trans. and ed. The Song of Roland. London: Penguin, 1990. |

CTP | Peter of Duisburg. Chronica Terre Prussie. In Scriptores rerum Prussicarum: Die Geschichtsquellen der preussischen Vorzeit bis zum Untergange der Ordensherrschaft, ed. Theodor Hirsch, Max Tppen, and Ernst Strehlke, 1:21219. Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1861. Translation mine. |

GDC | Gautier de Tournay. Lhistore de Gille de Chyn by Gautier de Tournay. Ed. Edwin B. Place. New York: AMS Press, 1970. Translation mine. |

GF | Hill, Rosalind, trans. and ed. Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolimitanorum. Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1962. |

HFC | Robert of Reims. Robert the Monks History of the First Crusade: Historia Iherosolimitana. Trans. and ed. Carol Sweetenham. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. |

HI | Robert of Reims. The Historia Iherosolimitana of Robert the Monk. Ed. D. Kempf and M. G. Bull. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2013. |

KVP | Nicolaus von Jeroschin. Di Krnike von Przinlant. In Scriptores rerum Prussicarum: Die Geschichtsquellen der preussischen Vorzeit bis zum Untergange der Ordensherrschaft, ed. Theodor Hirsch, Max Tppen, and Ernst Strehlke, 1:303624. Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1861. Unless otherwise stated, translation taken from Nicolaus von Jeroschin. The Chronicle of Prussia by Nicolaus von Jeroschin: A History of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia, 11901331. Trans. and ed. Mary Fischer. Farnham: Ashgate, 2010. |

PA | Guillaume de Machaut. La Prise dAlixandre. Trans. and ed. R. Barton Palmer. New York: Routledge, 2002. |

S | Saladin. |

A NOTE ON NAMES

Throughout this book, I have Anglicized geographical cognomina, except where the original is commonly used in historical and literary criticism. I will therefore refer to, for example, Robert of Reims and Graindor of Douai, but to Chrtien de Troyes and Guillaume de Machaut.

The Knight, the Cross, and the Song

Introduction

Toward the end of the fourteenth century, the English polemicist John Gower turned his attention to the Crusade, which was approaching its three-hundredth anniversary. Although he was not altogether opposed to the holy war, Furthermore, those who took up arms against the unbeliever were rarely driven by noble aspirations. In the Mirour de lOmme of ca. 13761379, Gower enumerated the reasons for which his contemporaries set out on Crusade, two of which he found especially reprehensible:

The first is (so to speak) pride in ones own prowessI will go in order to win praise. Or also, It is for my beloved, so that I may have her affectionfor this I will work. If you will work in pride for worldly vainglory, whereby you may be superior to the others, then you must give your garments and your wealth to the heralds, so that they may proclaim with great clamor your valor and largess. On the other hand, if it be that you go over the sea because of a woman of whom your heart is enamored, hoping that on your return the girl or lady for whom you have labored may deign to have pity on you, then you are lacking the right medicine.

Rather than to serve God, which alone made Crusade worthwhile by Gowers standards, his contemporaries were fighting out of a desire for worldly renown or to win the favor of women. Although Gower may not have liked it, the first of these motivations is perhaps not surprising. He specifically talks about the chivalric class, the knights who for many years had carried most of the burden of crusading, and as early as the eleventh century chivalry had found common ground between the desire to achieve glory through deeds of prowess and the wish to serve God.

An important body of Crusade scholarship has examined what motivated those who first left to fight for the cross. Although some have proposed socioeconomic and political motivations, Although individual piety undoubtedly played an important role, the critical preoccupation with religious motivations has obscured crucial aspects of Crusade propaganda, which exhibits far more breadth and complexity. This book examines how, from the very beginning of the Crusade in the last years of the eleventh century, historiographical works that propagated the holy war appropriated the formal and thematic characteristics of chivalric literary genres to appeal specifically to aristocratic interests that ranged