Contents

PART 1:

WOOD AND HUMAN EVOLUTION

PART 2:

BUILDING CIVILIZATION

PART 3:

WOOD IN THE INDUSTRIAL ERA

PART 4:

FACING THE CONSEQUENCES

Contents

Guide

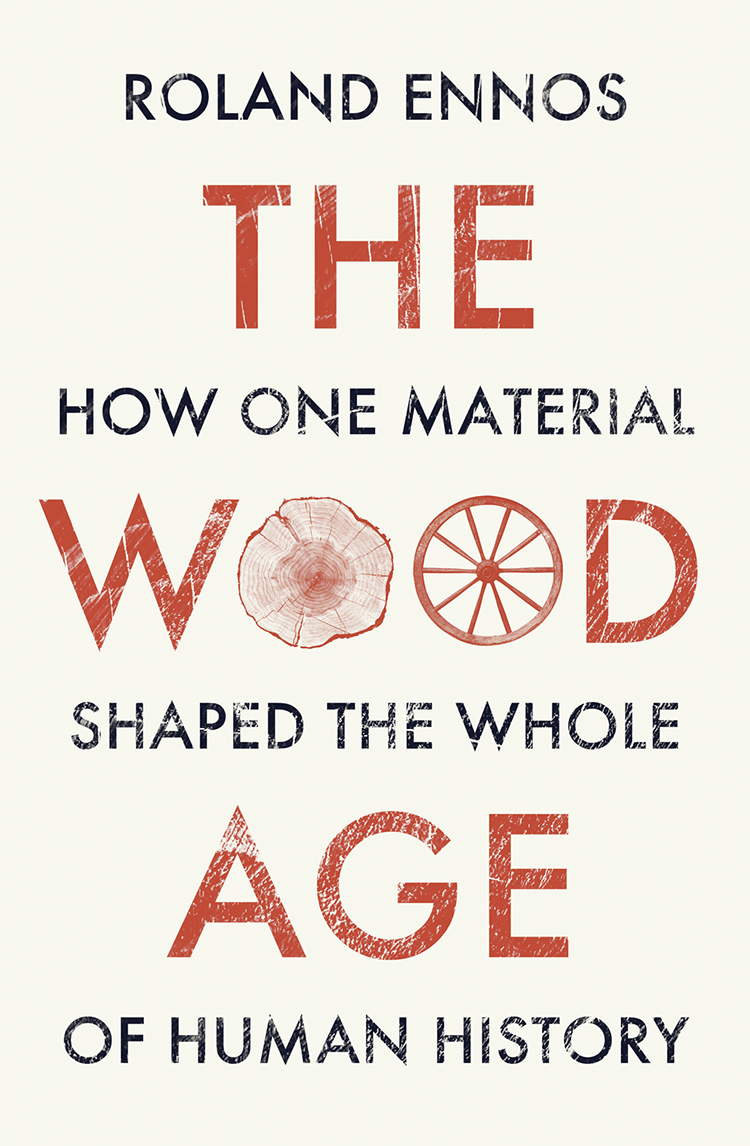

THE WOOD AGE

HOW ONE MATERIAL SHAPED THE WHOLE OF HUMAN HISTORY

Roland Ennos

Roland Ennos is a visiting professor of biological sciences at the University of Hull. He is the author of successful textbooks on plants, biomechanics and statistics, while his popular book Trees, which is published by the Natural History Museum, is now in its second edition. He is an enthusiast for natural history, archaeology and early music, and lives with his partner and several hundred ferns near Hull, in East Yorkshire.

When our ancestors came down from the trees, they brought the trees with them and remade the world.

Wood. We burned it to create fire. We fashioned it into tools. We built homes, roads, boats and cathedrals; became explorers, inventors, industrialists. We transformed the world.

This unique history of humanity tells the story of our evolution, our civilisations and our future through the lens of the material that made us.

Drawing together recent research and reinterpreting existing evidence from fields as far ranging as primatology, anthropology, archaeology, history, architecture, engineering and carpentry, Ennos charts for the first time how our ability to exploit woods unique properties has shaped our bodies and minds, societies and lives. He also charts the dislocating effects of industrialism and explains how rediscovering traditional ways of growing, using and understanding trees can help combat climate change and bring our lives into better balance with nature.

At 450,000 years old, the Clacton Spear, discovered in Essex, England in 1911, is the worlds earliest known wooden artifact. The point was sharpened with a stone blade, either when the wood was still green or after being charred in a fire. Archaeologists have interpreted the artifacts intended use in myriad ways: it could be the broken end of a digging stick, lance, or a spear.

The Natural History Museum/Alamy;

The ability to fell trees enabled Mesolithic people to build roomy round houses. The turf covering this reconstruction of an eight-thousand-year-old hut in Howick, Northumberland, hides a complex structure underneath, with a ring of posts supporting the rafters.

Clearview/Alamy;

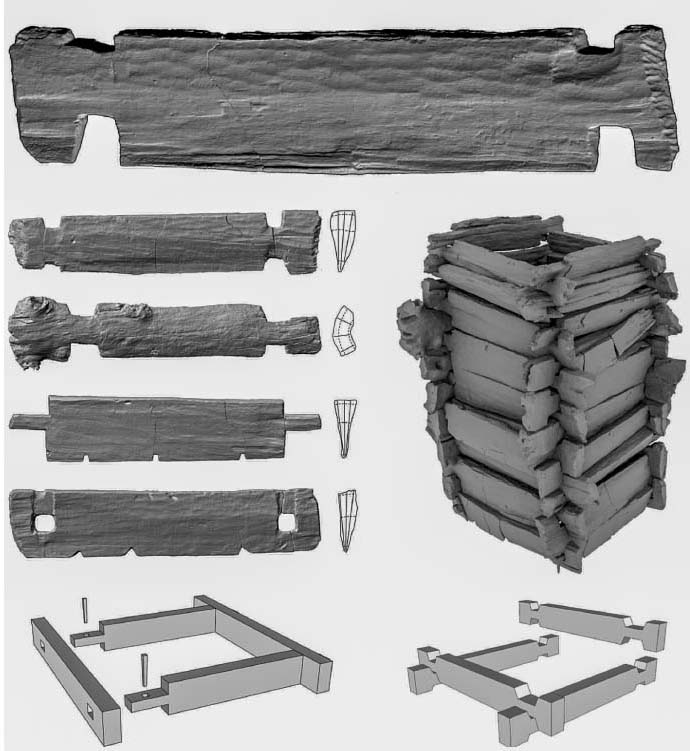

The first carpentry? In this 3-D rendering of a 7,300-year-old well lining from eastern Germany, the bottom of the frame features mortise-and-tenon joints, while the upper layers are joined by interlocking grooves. The rough ends to the planks show the difficulty Neolithic people had cutting wood across the grain before the advent of metal tools.

Tegel W. et al. 2012. Early Neolithic Water Wells Reveal the Worlds Oldest Wood Architecture. Plos One 7 (12): e51374;

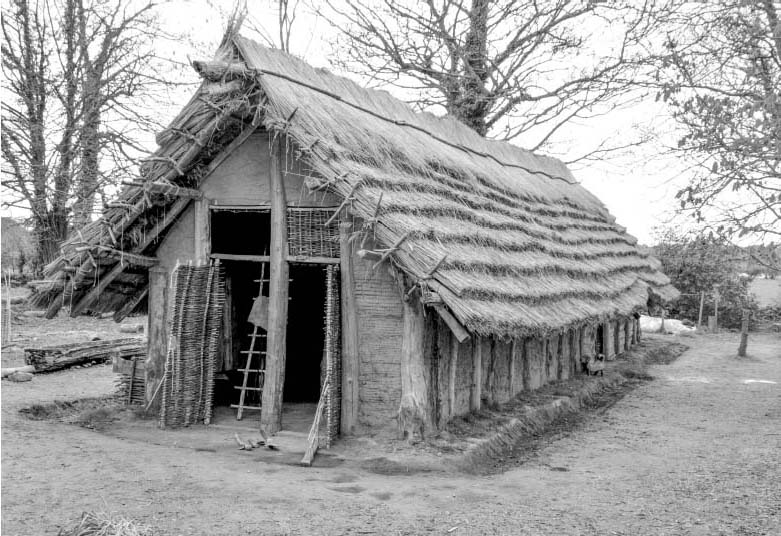

The tool innovations of the Neolithic LBK people allowed them to build long, narrow timber dwellings for multiple families. This reconstruction of a LBK longhouse from La Hougue Bie Museum in Jersey has a roof supported by five lines of poles, the outermost ones forming the walls, which are all dug into the ground, while the hurdle door is made from coppiced poles.

Philip Bishop/Alamy;

The 5,200-year-old Ljubljana Marshes Wheel is the worlds earliest surviving wheel and axle. The wheel is made from two planks joined by a series of battens (now broken) that fit snugly into grooves chiseled out of the planks. The square hole in the wheel fitted onto the axle and rotated with it.

Andrej Peunik/ Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana;

The reconstructed 4,500-year-old solar ship of Khufu, now in a museum next to the pyramids and sphinx at Giza, Egypt. Sealed disassembled in a pit at the foot of the Great Pyramid, the 143-foot long vessel was built to take the resurrected pharaoh across the sky. The short cedar planks were joined together with mortise-and-tenon joints as in many Bronze Age boats.

Stefan Lippmann/Oneworld Picture/Alamy;

Statue of Ka-Aper, around 4,500 years old, from the Cairo Museum in Egypt. Carved from sycamore, the statue presents the priest with a distinctive personality, in contrast to the idealized stone statues of the pharaohs. One can even see his receding hairline.

Werner Forman Archive/Egyptian Museum, Cairo/Heritage Images;

The prow of the early-ninth-century Oseberg ship from the Viking Museum, Oslo. Note the fine carving, graceful lines, and clinker construction of the hull. The individual strakes were riveted together with iron nails before an internal frame was added to strengthen the hull.

Jorge Tutor/Alamy;

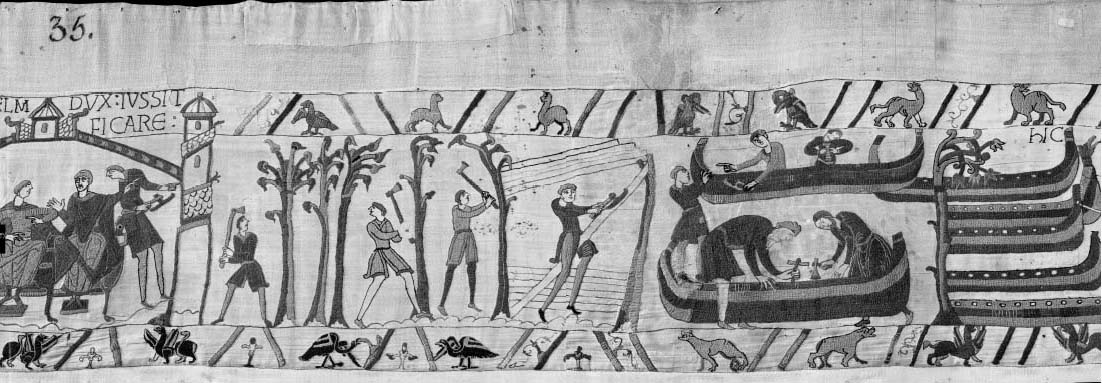

Detail of the Bayeux Tapestry from the eleventh century, showing the construction of William the Conquerors fleet for the Norman invasion of England. On the left, foresters fell trees, while in the center a carpenter shapes planks using a broadaxe. On the bottom right, workers shape the hull of a ship, while at the top right the shipwright assesses the alignment of the hull and a workman drills holes in it with an auger.

With special permission from the City of Bayeux;

Heddal Stave Church, built in the early thirteenth century near Telemark, Norway. In stave churches, the walls are made from lines of vertical split logs, or staves, while the main structure is supported by a framework of logs and beams and the roof is covered with wooden shingles.

Andreas Werth/Alamy;