This edition first published in 2019 by Weiser Books, an imprint of

Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

With offices at:

65 Parker Street, Suite 7

Newburyport, MA 01950

www.redwheelweiser.com

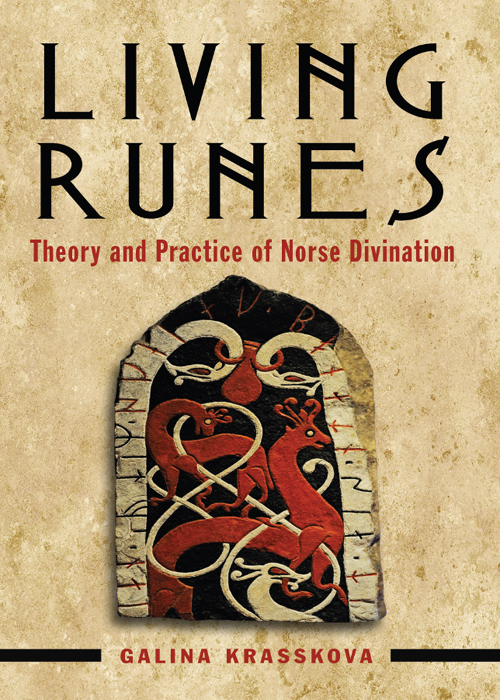

Copyright 2010, 2019 by Galina Krasskova

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. Reviewers may quote brief passages. Previously published in 2010 as Runes: Theory & Practice by New Page Books, ISBN: 978-1-60163-085-8.

ISBN: 978-1-57863-666-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Cover design by Kathryn Sky-Peck

Cover image PRISMA ARCHIVO / Alamy Stock Photo

Interior by Eileen Dow Munson

Printed in Canada

MAR

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

Dedication - - - - - - - - - - -

To my adopted mother,

who does not work the runes

and hates magic with a passion,

but who listened to early versions of this book

with the patience of a saint.

Ich habe dich unendlich gern auf Zeit und Ewigkeit, Mutti.

Thank you so much for everything.

And to those who taught me, with gratitude.

Acknowledgments - - - - - - - -

M any thanks to Raven Kaldera for allowing me to quote from his work on the Futhorc runes, and to Elizabeth Vongvisith for providing me with 32 beautiful modern-day rune poems.

To my friends and colleagues, who patiently tolerated my increasingly cranky mood as my deadline approached.

And, finally, to my editors at New Page books, most especially Michael Pye and Kirsten Dalley. It's been a pleasure working with you once more. Thank you for all your hard work!

C ontents

I ntroduction

T his is not an introductory book on runes, though it does cover the basic precepts. There are many good introductory books on rune-work available. I have noted several worthy texts in the Bibliography and Suggested Reading sections, and I encourage my readers to seek them out. Nor is this a historical overview of the runes, even though I am an academic. Although I believe that a clear understanding of the historical context in which the runes evolved is important, that is not the purpose of this book. Scholars debate whether or not the runes were ever used magically. As an Odin's woman, mystic, and rune worker speaking specifically to the Northern Tradition religious community, I know they were. I cannot write about runes in this particular context as an academic. So what, then, is the purpose of this book?

This is the book that I wish I had had access to when I was first starting out more than two decades ago. This is the book that I wish I could have given my first students when they came to me so long ago wishing to learn the runes. This book, which I believe is the first of its kind, is drawn from reams of notes that I developed over time and used to introduce students and apprentices to the runes. It offers a detailed description of what I believe, based on years of experience, to be the nature and lessons of each rune, and a systematic methodology for learning to access them.

Most importantly of all, it teaches the would-be rune-worker to approach the runes as living spirits and to develop a relationship with them as sentient, independent spirit allies. It presents a protocol of practice which, if diligently followed, will enable the saavy rune student to work as painlessly as possible in this art, avoiding many common pitfalls. With the exception of a brief section in Raven Kaldera's Northern Tradition Shamanism series (available through Asphodel Press), I know of no other book on runes that discusses their nature as living beings and what that means for the rune worker. This book fills that gap.

I begin this book with an exegesis on the story of Odin's winning of the runes by sacrifice. Drawing on comparative mythologies throughout Northern Europe as well as developing practices within contemporary Heathenry, I will explore the ideas of ordeal, sacrifice, pain, agency, and power as they relate to the runes. Subsequent chapters look at the theory and practice of magic, the art of galdr, the craft of divination, and potential ethical problems inherent in this type of work. explores the individual runes one by one, including both the Elder Futhark and the younger Anglo-Saxon Futhorc. Much of this chapter is drawn directly from my personal gnosis as a rune magician and diviner. Finally, a thorough list of resources is provided.

This book presupposes a reasonable knowledge of Norse cosmology and a basic knowledge of energy-working skills (that is, magic). It also presupposes a desire to interact on some authentic level with the Norse Gods and Goddesses. The study of runes can be difficult and challenging but it can also be immensely rewarding. I encourage each of my readers to use this book as a stepping stone toward developing their own unique and individual relationship with the runes. Ultimately, to quote an Estonian proverb, the work will teach you how to do it. Good luck.

Odin: The First Rune-Master

O din is the high God in the Northern Tradition. In both the surviving sources and in modern Heathenry, He is referred to variously as the All-Father, Victory Father, Hanging God, Old Man, or Old One-Eye.

The story of Odin's primary ordeal is told in the Havamal, one of the lays of the Poetic Edda. The reader is told that in search of wisdom, Odin hung Himself for nine days and nights on Yggdrasil, the World-Tree. Although Odin is usually viewed as a God of kingship, He also holds a place within the Northern Tradition as a God of shamans. The idea of a great cosmic The Tree shows up again in Jewish Cabbala in the guise of the Tree of Life, and has one of its earliest manifestations in Sumerian stories of the Goddess Inanna. It is by traversing the World-Tree that Odin is able to move from His role as sacred king to that of Shaman. The key to this transition from temporal to liminal power was His sacrifice by hanging.

During this ordeal, He starved Himself and stabbed Himself with His own spear, shedding His own blood. Eventually He died. It is through His death and rebirth that He gained access to the runes, the keys to the secrets of the universe:

I ween that I hung on the windy tree,

Hung there for nights full nine;

With the spear I was wounded, and offered I was

To Othin, myself to myself,

On the tree that none may ever know

What root beneath it runs.

Odin then recited the charms that He learned, and set down the formula for making appropriate sacrifices by providing a list of ritual acts including divination, blood offering, petitioning the Gods and making actual sacrifice. Odin's sacrifice permeates modern Heathen consciousness. It is one of the defining moments in the religion's mythos.

The use of pain as a spiritual tool is quite controversial in modern Heathenry. It is, however, part and parcel of yet another Shamanic practice with which Odin is associated. Although Northern Tradition Shamanic practices are somewhat outside the scope of this book, the idea of sacrifice (whatever that might mean to the individual) to gain wisdom is deeply entrenched in the core cosmological ethos of northern religions. This has evolved within a small subsection of the modern Northern Tradition into the practice of ordeal work.

Ordeal work refers to a body of practices used to bring about a deep catharsis for purposes such as self-growth, religious sacrifice, or a rite of passage. These practices quite often involve physical pain, and are usually done in a spiritual or at least a carefully crafted context. Practitioners maintain that when utilized in a controlled manner, ordeal practices have the power to heal, transform, and render the practitioner receptive to their Gods.

Next page