Translation, introduction, and notes copyright 2021 by Sarah Ruden

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Modern Library, an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Modern Library and the Torchbearer colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ruden, Sarah, translator.

Title: The Gospels / translated by Sarah Ruden.

Other titles: Bible. Gospels. English. Ruden. 2021.

Description: First edition. | New York: Modern Library, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020032892 (print) | LCCN 2020032893 (ebook) | ISBN 9780399592942 (acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780399592959 (ebook)

Classification: LCC BS 2553 . R 83 2021 (print) | LCC BS 2553 (ebook) | DDC 226/.05209dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020032892

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020032893

Ebook ISBN9780399592959

modernlibrary.com

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Simon Sullivan, adapted for ebook

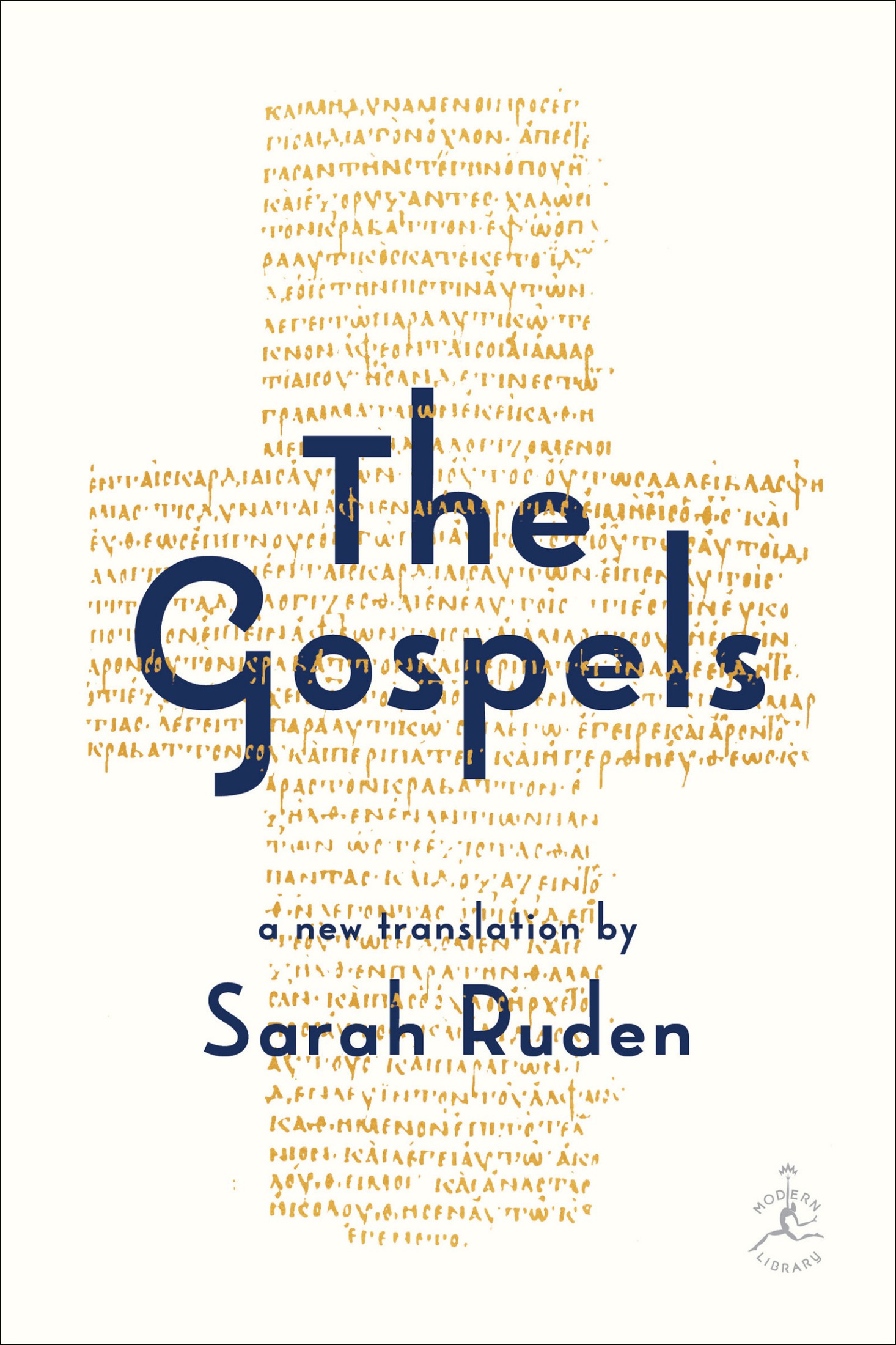

Cover design: Lucas Heinrich

Cover image: Codex 047 (Gregory-Aland), manuscript of the Greek New Testament, 8th century, with the text from the Gospel of Mark 2:415

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Contents

It seemed now as if, touched by human penitence and all its toil, divine goodness had parted the curtain and displayed behind it, single, distinct, the hare erect; the wave falling; the boat rocking, which, did we deserve them, should be ours always. But alas, divine goodness, twitching the cord, draws the curtain; it does not please him; he covers his treasures in a drench of hail, and so breaks them, so confuses them that it seems impossible that their calm should ever return or that we should ever compose from their fragments a perfect whole or read in the littered pieces the clear words of truth. For our penitence deserves a glimpse only; our toil respite only.

Virginia Woolf , To the Lighthouse

Introduction

As a Quakera member of perhaps the least theological, most practical religious movement in the worldIm supposed to be open to looking first at a thing in itself, whether its a head of Swiss chard, money, a gun, a book, a belief, or anything else. As a Quaker translator, I would like to deal with the Gospels more straightforwardly than is customary, to help people respond to the books on their own terms. Yet never before, in nearly forty years of translating, have I found texts so resistant to this purpose.

But first of all, what are the Gospels? Scholars of ancient literature (Im one of those too), who are used to classifying works within well-defined categories (known as genres), tend to feel that the Gospels are not quite like anything else. This is signaled by their shared name. In the original Koin (Common) dialect of these Greek texts, the title that emerged is euaggelion (the double g is pronounced ng), meaning good news. Our word Gospel comes from an Old English word for that, and Gospels is used in the title of this book and in all parts of the book outside the translations themselves, in order to avoid confusion.

The title is unusual in being so general. Ancient books normally got their permanent names (a process that might take some time) from the authors (or purported authors) name or other designation, or from the subject matter or the form of the writing. Ezekiel, Kings, and Proverbs are biblical examples. In contrast to all this, good news is extremely broad and confident, as if four short narratives carry a revelation sweeping aside all others.

The four texts are differentiated up front by authorial names, as the good news according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, but that is not the usual way of ascribing authorship in antiquity. People were normally considered to have composed works, with far-reaching originality, even if they happened to credit the Muses, another deity, or the literary tradition itself, and even if the name of the author is a prestigious pseudonym. But the four evangelists, or good-news-ists, are presented right away, by that according to wording in the Gospel titles, more as four witnesses to the same events, or as four messengers bringing different reports on these.

Their role in this is startlingly impersonal by comparison. Perhaps the most similar of the major fields of pagan literature, historiography and biography, saw authors regularly vouching for their own reliability: I was there, or I reported in this way, for these reasons, or just These are the principles I bring to this task. (The comic writer Lucian, of the second century C.E. , was so sick of these conventions that in the preface to his True History he boasts, in the conventional style, of writing pure lies out of empty-headed conceit.) Long stretches of the Hebrew Bible can seem rather detached, but Hebrew prophets and other scriptural authors and speakers are preoccupied by their qualifications to purvey divine messages, or perhaps this preoccupation was written into the text by others.

In contrast, with the exception of the four-verse introduction to Luke and the last two verses of John, the Gospels writerly point of view is omniscient with a vengeance. In fact, as far as we know, none of the texts was even attributed to a specific writer until around the end of the second centurythat is, about a century after the latest Gospel, Johns, appeared: for all the time intervening, apparently, all four works could do without the normal clear signal of a controlling human voice in the background. Mark and Luke the persons are so obscure as to appear only in the titles of their Gospels.

Of course, eyewitness testimony, at whatever remove, was vital to the existence of the Gospels; strong oral traditions helped to form them. Two of the versions, Matthew and John, carry names of Jesus followers who appear (in flashes) as actors in the narrative; but claims that they were the actual authors are far-fetched, serving mainly to promote these texts as direct, if reverently passive, testimonies to Jesus mission. Mark and Luke, particularly because of their association with the spread of proto-Christianity, are better candidates for having had styluses in hand. A John Mark is named in the New Testament Acts of the Apostles (covering about thirty years after Jesus death) in connection to another original follower of Jesus, Simon or Peter. Luke, an associate of the early missionary Paul, was quite probably the author of the Gospel credited to him as well as of Acts. (The Pauline letters, or Epistlessome genuine, some pseudonymousare discursive works that counterbalance in the New Testament the mainly narrative Gospels and Acts.)

In the Gospels content, the contrast is even sharper. In these new works, there is really only one figure, and only one voice. Just to consider the realm of scripture, the Hebrew Bible contains a variety of compelling personalities, sometimes shown in intricate counterpoint to one another. But in the Gospels no one is essential but Jesus. (The name is a later form of Joshua, the Hebrew Bible hero of the conquest of Canaan.) Very nearly everyone else who speaks and moves in the texts does so only in relation to him and is defined by the degree of either fervor for or opposition to him. Until the crucifixion, he is largely above opinions and events, choosing purposes, companions, and destinations for no stated reason and performing a widely varying set of miracles with an odd mix of publicity and (mostly ignored) requests for secrecy, most of the time without the traditional prophetic crediting of God; the most frequent basis cited is that the beneficiary had faith in himself, Jesus. He enjoys hospitality without asking for it and eludes violence without effort. He appropriates even expensive conveyanceson several occasions a boat, and one day a beast that is probably a donkey in all four Gospelswithout consequence.