This book is published with the assistance of a grant from the McLellan Endowed Series Fund, established through the generosity of Martha McCleary McLellan and Mary McLellan Williams.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS book is the culmination of many years work, and throughout the process, I have been fortunate to have been supported and sustained by a number of wonderful institutions and individuals. I would like to thank a few of them here.

The project found its genesis in 2004 when as a Getty Research Institute Visiting Scholar I had the opportunity to avail myself of the remarkable resources and robust community of scholars gathered at the Getty Center in Los Angeles. This time of intensive reading and research allowed me to formulate the early stages of this project, which became the foundation of all that followed. Subsequent stages of research and fieldwork were generously supported by George Mason University, whose leave policies and summer research grants were crucial to my work. I am fortunate to work at a university that actively cultivates faculty research.

As the project grew, becoming at times ungainly and awkward, it was the advice, guidance, and insight of colleagues and friends that helped me find my way. Although a great many were instrumental in assisting me, I would like to particularly thank Akira Shimada, Abhishek S. Amar, Monika Zin, Tamara Sears, Santhi Kavuri, Paul Harrison, Cary Shaffner, Monica Smith, Susan Fernsebner, Deborah Diamond, Finbarr Barry Flood, Benjamin Bogin, Michael Chang, Nicholas Morrissey, Pia Brancaccio, Oliver Freiberger, Kurt Behrendt, Michelle C. Wang, Juhyung Rhi, and Scott Wilson. Their words, knowingly or not, saved me from many embarrassments. In addition to these people, I would like to offer a special thanks to my students, both past and present, for their inquisitive and perceptive questions that have helped me to clarify and justify my own ideas. Working with gifted graduate students such as Anne Brennan Hardy, Jessica Farquhar, Roshna Kapadia, Shellie Meeks-Shaffner, and Ilavenil Ramiah has been especially helpful.

I express special gratitude to the directors, faculty, and students of Deccan College, Pune, whose hospitality and expert advice made my fieldwork far more effective than it might have been otherwise. The Archaeology Department under Professor Vasant Shivram Shinde was exceedingly generous in hosting me during my stay. I need to reserve special thanks, however, for Dr. Shrikant Ganvir,who organized the visit, and who, together with Gopal S. Joge, was an excellent travelling companion. I am deeply in debt to their good-natured patience and vast knowledge. I offer my sincere thanks to them both.

Regan Huff has been the finest editor that anyone could hope for. The patient guidance provided by Regan, Jacqueline Volin, and Tim Zimmermann at the University of Washington Press has been invaluable. I also wish to thank my two anonymous readers, whose thoughtful comments and criticisms were exceptionally helpful and are greatly appreciated.

Finally, I need to thank my family and friends, without whose support, encouragement, and timely diversions this project would not be complete (or possibly may have been completed sooner but would have been far less fun). To them, my love and gratitude always.

1

PROBLEMS AND PRECONCEPTIONS

Each time one sees it, your body gives new joy

For its sight cannot ever satiate, its aspect is so pleasing.

Where else would these virtues of a Tathgata [Buddha] be well housed?

Except in this form of yours, blazing with signs and marks.

Mtceas hymn to the Buddha in the atapacatkastotra

[The Buddha said:] What do you think, Kyapa, is any... human or non-human even able to make an image of the Tathgatas [Buddhas]? Kyapa said: No, Blessed One. Since a Tathgata is unexpressible, his body inconceivable, because of that it is not easy to make an image of them.

Kyapa and the Buddha discussing images in the Maitreyasihanda Stra

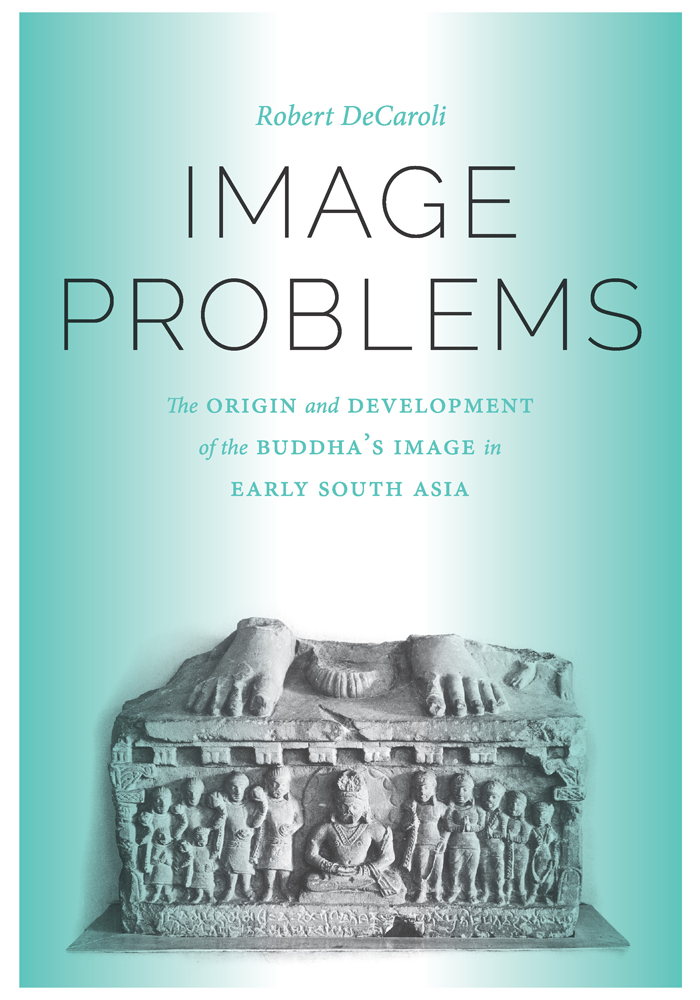

IN the decades following the start of the first century CE, Buddhists in South Asia had a great deal to say on the subject of images and their use in religious contexts. Yet for all this information, it is futile, or at least misleading, to ask for a singular response to the question of what they thought about visual representations of the Buddha. Although it can be difficult to accurately date textual sources, it is safe to say that views on image use varied widely, and the views of individual authors only occasionally conformed to those expressed by other Buddhists.

The Divyvadna, for example, includes tales of monks achieving advanced spiritual states merely by seeing a copy of the Buddhas bodily form.

It would seem that under the placid surface of the waters we collectively refer to as Buddhism there were deep currents pulling in very different directions. Although we can now look back on these texts and deduce that they represent a range of views shaped by sectarian affiliation, regional factors, historical shifts, and individual beliefs, the texts rarely identify themselves in such fashion and frequently claim to speak with the authority of the Buddha himself.

If we need to be cautious in making general claims about Buddhist ideas on image use, we also need to be wary of treating the Buddhist acceptance of figural art as something that happened at a singular moment or for a singular reason. What emerge from the sources, both textual and material, are a rich variety and wide range of views that never actually coalesce into a single, pervasive point of view. This book constitutes a portrait of an uneasy relationship between the Buddhist authors and depictions of their Teacher, whose form is sometimes rejected entirely, frequently tolerated, and rarely embraced unconditionally. Most typically, Buddhist sources produced during and after the first century adopt a middle ground between outright rejection of and total comfort with image use. These sources are replete with explanations, justifications, and restrictions seeking to regulate the viewers relationship to the art.

Given the piecemeal nature of the historical evidence, a comprehensive catalogue of the full spectrum of South Asian Buddhist views on images use is not possible. What is possible is a study of the major concepts, concerns, and issues that recur in the textual sources or can be traced in the archaeological remains. This book is an attempt to understand the history of Buddhisms relationships with figural art as an ongoing set of negotiations within the Buddhist community and in society at large. Any hope of understanding early Buddhists views on figural art requires that we situate these individuals within the world they inhabited and examine the cultural practices and concepts they would have considered familiar.