John James Audubon (17851851), The Birds of America, 18271838; Great blue heron.

How Zoologists Organize Things

The Art of Classification

DAVID BAINBRIDGE

Introduction

A nimals were among the first subjects drawn by the hand of man. Many early rock paintings are either representations of animals, or tracings of our thumby hands a distinctively human attribute that sets our bodies apart from those of beasts, and classifies us as something different. We assume that our long-standing urge to make sense of the bewildering variety of animal life often had a practical basis to differentiate the edible from the toxic, the ferocious from the tractable, for example but there have always been artistic drives, too.

Long before Darwin, or Crick and Watson, our ancestors were obsessed with the visual similarities and differences between the creatures that inhabit the Earth alongside us. Early savants could sense there was an order, a scheme, that unified all life. And the classifications they formulated often tell us as much about humans motives as they do about the animals they strove to organize.

Creatures were, indeed, organized in abundance. The human quest to classify living beings has left us with a rich artistic legacy in four great stages, in the West at least: the folklore and religiosity of the ancient and medieval worlds; the naturalists cataloguing of the Enlightenment; the evolutionary trees and maps of the nineteenth century; and the modern, computer-hued classificatory labyrinth. Those four stages form the structure of this book.

We are told that zoological distinctions started early. On the fifth day of the Judaeo-Christian creation myth, God made the animals of the sea and air, but waited until the sixth to make the creatures of the Earth, man notably included. Even before Christianity took hold in Europe, zoological classification flourished around the Mediterranean ancient Egyptians painted inventory-murals of edible animals and plants, while Aristotle formulated classificatory systems whose essence survives today. However, the surviving visual corpus of Western animal classification really begins during the High Middle Ages some time in the twelfth century. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this early phase of bestiaries and encyclopedias reveals a world where animal diversity was forcibly reconciled with the Christian world view. For centuries, animals occupied immutable hierarchical levels of strictly gradated religious scalae naturae (scales of nature), while ferocious beasts some real, some less so populated the terrifying margins of mappae mundi (maps of the world). Most of all, lavishly illuminated bestiaries initiated the compulsive cataloguing of animal forms that was to persist, in slowly evolving form, into modern modes of zoological organization.

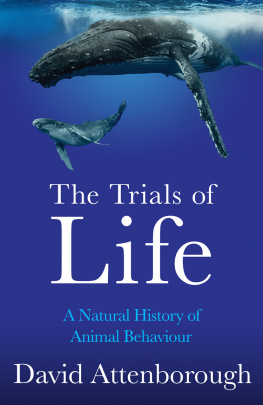

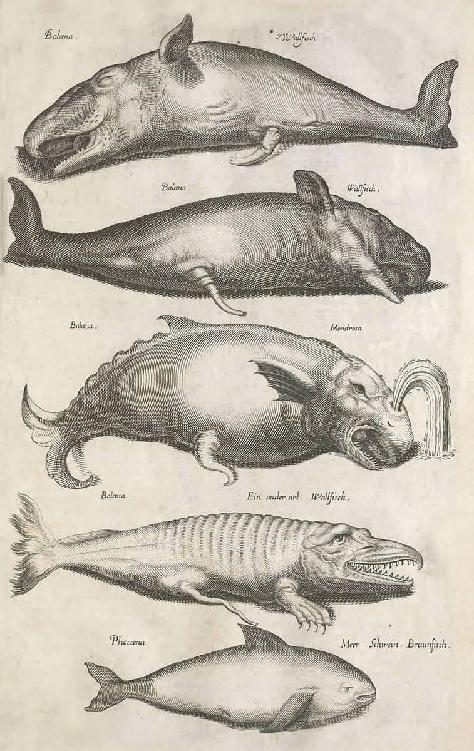

The second phase in our story, the eighteenth century, brought a change of tone. Advances in art and science during the Renaissance, along with a yearning to return to an idealized conception of classical philosophy, had already led to new ways of seeing the world and its inhabitants. Now, animals began to be classified less according to the religious lessons they might teach us, and more by their objectively measurable similarities and differences. Close relations and distant relations, shared characteristics and distinguishing characteristics, possibly even ancestors and descendants all pointed to underlying processes and hidden patterns of organization. Although seldom explicitly stated, it began to seem as if animals differ or are similar for reasons other than Gods plan maybe distinct animal types are actually related like members of a family; maybe they could even change. The incompleteness of these nascent ideas of natural history appears to have been a tantalizing challenge to the inquiring Enlightenment mind, and a flourishing of the naturalist/systematizers art ensued, with creatures continually drawn, etched and painted into new organizational schemas.

Jacob van Maerlant (c.12351291), Der Naturen Bloeme, c.1350; Bird, with teeth.

Joannes Jonstonus (16031675), Historiae Naturalis de Piscibus et Cetis Libri V, 16501653; Whales.

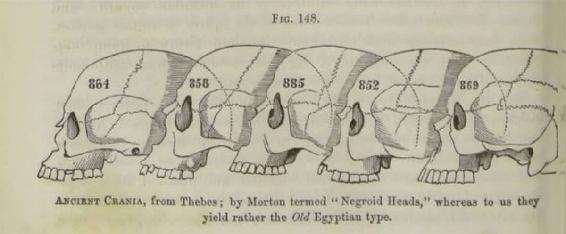

Josiah Nott (18041873) and others, Types of Mankind, 1854; Modern skulls the fellahs of Lower Egypt.

Then, in the third phase, three new scientific insights were to drive the art of zoological classification in the nineteenth century. It was realized that animal species do indeed evolve change and split over time; Darwin and Wallace discovered the process of natural selection, which allows that evolution to take place; and the world was shown to be sufficiently ancient for evolution to have occurred, and indeed its rocks contain the neatly stacked fossil evidence of that process. Suddenly, evolution was real, it had a mechanism, and it had sufficient time, too. Yet it all seemed rather irreligious: all animals, including humans, had become linked by common ancestry, and geology, zoology and anthropology were united as well. As a result of these advances, nineteenth-century depictions of animal classification developed unmatched boldness and certainty. All nature could be elegantly and artistically summarized in a gnarled tree, a methodical table or an authoritative-looking map. Moreover, as Europeans diligently catalogued the fauna of distant continents, their native animals strangeness and variety confirmed the new theories being formulated back at home.

The fourth phase of animal-organizing, the period since 1900, has been about much more than just accumulating more information. The deeper we peer into biological processes, the more meaningful animals similarities and differences become. Species evolve and differentiate, but so do genes, chromosomes and genomes. Animals change, fossilize, adapt and interact in many ways confusing ways that challenge the artist who depicts them. The neat evolutionary trees have become dense thickets, and the quest to untangle animal relationships has led to a range of strangely named disciplines phylogenetics, taxonomy, chromosome mapping, phenetics, systematics, biostratigraphy, taphonomy, genomics. Compounding this complexity is the realization that animals interact in non-evolutionary ways as well ecology, behaviour, symbiosis, parasitism, biomechanics, biophysics, environment and extinction. Yet now the richness of the scientific information is almost overwhelming, we can render it artistically beautiful in our attempts to tame it. As a result, the recent history of the art of animal classification has been the most diverse of all.

Again and again, we will see that illustrating animal variety leads people to do more than is strictly necessary. Sometimes the meticulousness of zoological cataloguing can seem pathologically obsessive, and the information it generates fills libraries with so many beautiful images that we rarely have time to look at most of them. Also, the artistic beauty of those images often exceeds what is required merely to report data or support a scientific theory. Again and again, there is descriptive and artistic overkill, as if a superabundance of striking visual representations may in itself somehow guide us towards deeper philosophical truths.