Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture

SERIES EDITOR

William A. Johnsen

The Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture Series examines issues related to the nexus of violence and religion in the genesis and maintenance of culture. It furthers the agenda of the Colloquium on Violence and Religion, an international association that draws inspiration from Ren Girard's mimetic hypothesis on the relationship between violence and religion, elaborated in a stunning series of books he has written over the last forty years. Readers interested in this area of research can also look to the association's journal, Contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis, and Culture.

ADVISORY BOARD

Ren Girard, Stanford University

Andrew McKenna, Loyola University of Chicago

Raymund Schwager, University of Innsbruck

James Williams, Syracuse University

EDITORIAL BOARD

Rebecca Adams, Independent Scholar

Jeremiah Alberg, International Christian University

Mark Anspach, cole Polytechnique, Paris

Pierpaolo Antonello, University of Cambridge

Ann Astell, University of Notre Dame

Cesreo Bandera, University of North Carolina

Maria Stella Barberi, Universit di Messina

Benot Chantre, L'association Recherches Mimtiques

Diana Culbertson, Kent State University

Paul Dumouchel, Ritsumeikan University

Jean-Pierre Dupuy, Stanford University, cole Polytechnique

Giuseppe Fornari, Universit degli studi di Bergamo

Eric Gans, University of California, Los Angeles

Sandor Goodhart, Purdue University

Robert Hamerton-Kelly, Stanford University

Hans Jensen, Aarhus University, Denmark

Mark Juergensmeyer, University of California, Santa Barbara

Cheryl Kirk-Duggan, Shaw University

Michael Kirwan, SJ, Heythrop College, University of London

Paisley Livingston, Lingnan University, Hong Kong

Charles Mabee, Ecumenical Th eological Seminary, Detroit

Jzef Niewiadomski, Universitt Innsbruck

Wolfgang Palaver, Universitt Innsbruck

Martha Reineke, University of Northern Iowa

Joo Cezar de Castro Rocha, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro

Tobin Siebers, University of Michigan

Thee Smith, Emory University

Mark Wallace, Swarthmore College

Eugene Webb, University of Washington

Copyright 2014 by Michigan State University; Celui par qui le scandale arrive 2001 by Descle de Brouwer

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Michigan State University Press

East Lansing, Michigan 48823-5245

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

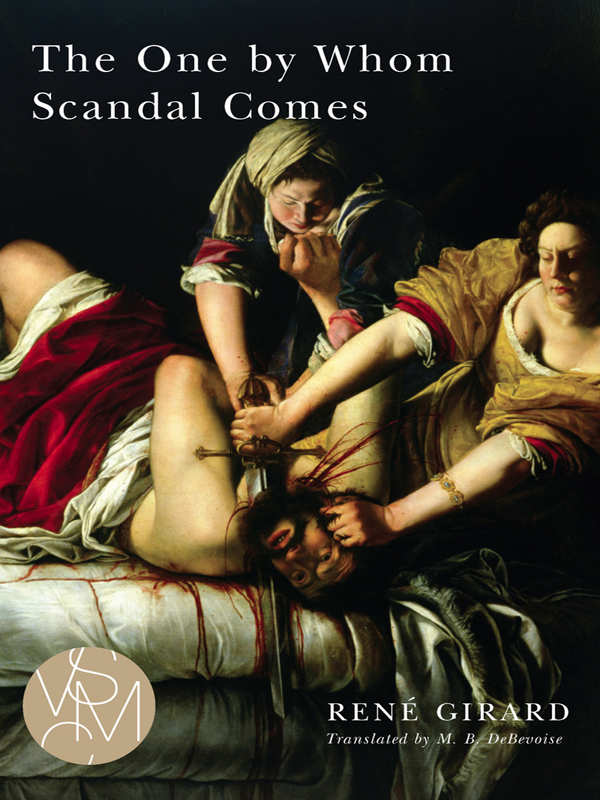

Girard, Ren, 1923

[Celui par qui le scandale arrive. English]

The one by whom scandal comes / Ren Girard; translated by M. B. DeBevoise.

pages cm. (Studies in violence, mimesis, and culture series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60917-399-9 (ebook)ISBN 978-1-61186-109-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. ViolenceReligious aspects. I. Title.

BL65.V55G56513 2014

261.7dc23

2013012137

Book design and composition by Charlie Sharp, Sharp Des!gns, Lansing, Michigan Cover design by David Drummond, Salamander Design, www.salamanderhill.com Cover art is Judith and Holofernes, 161221 (oil on canvas), Gentileschi, Artemisia (1597 c. 1651) / Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy / Alinari / The Bridgeman Art Library. Used with permission.

Michigan State University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative and is committed to developing and encouraging ecologically responsible publishing practices. For more information about the Green Press Initiative and the use of recycled paper in book publishing, please visit www.greenpressinitiative.org.

Visit Michigan State University Press at www.msupress.org

ISBN 978-1-62895-016-8 (ePub)

ISBN 978-1-62896-016-7 (Kindle)

A Note on the Translation

In the matter of scriptural citation I have quoted from the New American Bible, the verse numbering of which sometimes differs from Protestant bibles, and added a number of notes identifying various passages alluded to in the text. I have, however, followed the author in preferring the New King James Version's rendering of the famous phrase from Matthew 12:26, Satan casts out Satan.

A modest amount of bibliographical information has been added, as well as some biographical detail in the case of persons who may not be well known to general readers. Several minor errors of fact have been silently corrected as well.

I am grateful to Professor William A. Johnsen for his careful scrutiny of a draft version.

Preface

The one by whom scandal comesa rather grand and somewhat incriminating title, suggested by Maria Stella Barberi, who assures me that in proposing it to Benot Chantre at ditions Descle de Brouwer in Paris she did not have the author of the present work in mind! She was inspired, she says, by the topics I discuss, which bear on all the most controversial points of mimetic theory.

In the three essays that make up the first part of this book, as well as in the conversation with Maria Stella Barberi that comprises the second part, I respond to objections that have long been brought against my work, as well as to questions never treated, or only lightly touched upon, in my earlier books. At the same time I continue to explore a number of themes that are dear to my heart, giving more specific and more modern examples than I have done in the past.

In the first essay, after a brief mimetic analysis of contemporary terrorism, I take up the problem of conflicts that frequently erupt among persons who are indifferent to one another, whom desire neither brings closer together nor pulls apart. These conflictseven (and above all) the most pointless ones of their kindare also mimetic, for they are rooted, like so many others,in a widely shared desire for something that cannot be shared. Mimeticism is the very substance of all manner of human relations.

In the second essay I turn to the question of ethnocentrism, for which my anthropology is often reproached. Those who protest against Western ethnocentrism imagine themselves to owe nothing to the West, since after all they rage furiously against it. But in fact theirs is the most Western perspective of all, more Western than that of their adversaries.

Not only is the revolt against ethnocentrism an invention of the West, it cannot be found outside the West. Its first great literary success was Montaigne's famous essay Of Cannibals, now more than four hundred years old. Montaigne's anti-Western rhetoric, not always very sincere, was the opening salvo in a long war conducted exclusively against the ethnocentrism of the West. This struggle produced its finest masterpieces in the eighteenth century. Then, following a lull, it resumed after the Second World War with even greater ferocity.

The most recent phase is marked by a renunciation of the elegance and wit of our illustrious ancestors in favor of very twentieth-century neologisms, among them the graceless word ethnocentrism itself. In this way the rococo bibelots of the century of the Enlightenment have come to be coated with a rather thick layer of varnish. Whereas Montesquieu tried to imagine what it would be like to be Persian, our contemporaries ponderously rail against the West's preoccupation with itself. At bottom, however, the debate has scarcely changed.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).