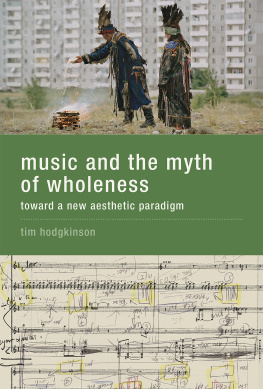

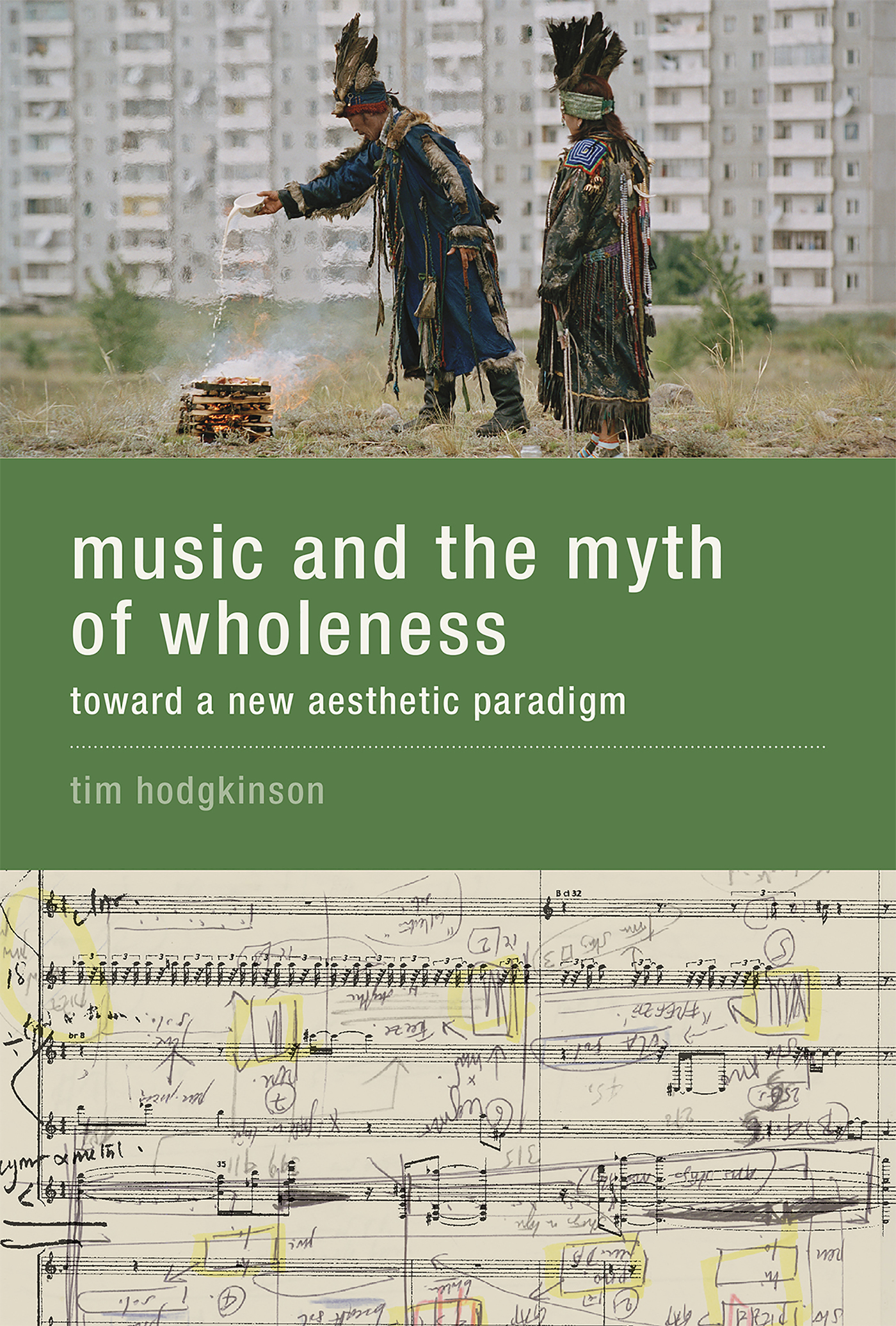

Music and the Myth of Wholeness

Music and the Myth of Wholeness

Toward a New Aesthetic Paradigm

Tim Hodgkinson

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2016 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hodgkinson, Tim.

Title: Music and the myth of wholeness : toward a new aesthetic paradigm / Tim Hodgkinson.

Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, [2015] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015038318 | ISBN 9780262034067 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Music--Philosophy and aesthetics. | Aesthetics. | Aesthetics--Social aspects.

Classification: LCC ML3845 .H62 2015 | DDC 781.1/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015038318

EPUB Version 1.0

For Micol

Contents

Polarization of Order and Indeterminacy

Discursive Subject

Indeterminacy in Contemporary Art

Silences

Ritual Body/Ritual Subject

Transition and Affliction

Ontological Moment of Ritual

Anthropology

Sociology versus the Aesthetic Object

Formalism

Art and Ritual

Incubation of Western Art Music

Art and Society

Musical Space in the Renaissance

Social Difference and Subjectivity

On the Sensations of Tone

Ici-bas

Your You versus Your Brain

Recursivity in Aesthetic Production

Aesthetic Worlds (1)

Hamburg, January 2010

Field Recordings, Xenochrony, and Charles Ives

Aesthetic Worlds (2)

The Fifteenth Quartet

The Other of Music (1)

Ut at the Luminaire

The Other of Music (2)

Form and Formativity

Aesthetic Risk

Ontological Power of Music

Expression

John Cage and the Wandering Subject

Pierre Schaeffer and the Sonorous Object

Helmut Lachenmann and the Learning Subject

Ethnomusicology

Embodiment and Enactive Aesthetics

Acknowledgments

This is a book that has come together gradually over a long period. Phases of writing have been scattered through the working life of a musician. Countless people over years have therefore unwittingly contributed to it: chance remarks, turns of conversation, mentions of musics, films, books, and a new connection is made. I cannot name them all, but here are a few.

Micol Vacca, who introduced me to a whole tradition of Italian aesthetic thoughtPareyson, Vattimo, Perniolamade numerous criticisms, interventions, and suggestions; provided material on psychology, critical theory, and linguistics; gave me working space; and goaded me along. I tried out ideas, argued, or corresponded with David Connearn, Harry Gilonis, Keith Howard, Kersten Glandien, Chris Cutler, Valentina Suzukey, Chris Frith, Tom Lubbock, Carole Pegg, Ben Piekut, and Malise Ruthven, all of whom gave me encouragement. Ben Piekut deserves a medal for reading and criticizing an entire early draft that was more or less unreadable; Malise Ruthven also; Tiggy and Malise for much hospitality; Ken Hyder for several helpful reads and rereads at various stages; Iancu Dumitrescu and Ana-Maria Avram for day-long discussions about music, phenomenology, and much else; Lu Edmonds, Phil Minton, Odile Jacquin, and Robert Worby for various helps; Peter Hodgkinson and Noele Bellier and Bella the dog for inspiration; Robert Reigle for his encyclopedic knowledge of contemporary music and discussions on ethnomusicology and spectralism; and Doug Sery at the MIT Press for warm support for this project.

Ken Hyder and Gendos Chamzyryn, whom I joined in the K-Space project, and many friends and acquaintances in Tuva and throughout Siberia and Russia, including Boris Podkosov, Anatoly Kokov, Spartak Chernish, Tania Jamatshuk, Boris Tomilov, Tamara, Boris Tolstobokov, Valentina Ponomareva, Konstantin Gogunsky, Sainkho Namtchylak, Chai-Su, Ai-Churek, Vladimir Rezitsky, Eugene and Olga Kolbashev, Nicolai Michailov, Yeremi Hagayev, Kunga-Boo Tash-Ool, Mongush Kenin-Lopsan, Doptchun Kara-Ool Tyulyushevich, Bolot Biryshev, Vlail Kaznacheev, Alexander Trofimov, the Barnaul Healthy Living Association, Kolya and Lyuda Dmitriev, Sergei and Marfa Rastarguev, Albert Kuvezin, Alexei Sayaa, Sasha Mezdrikov, Grigori Valov, Sergei Dykhov, Kongar-Ool, Sayan Bapa, Radik Tulush, Stepan Manzyrykchy, Alexei Kagai-Ool, Sergei Tumat, Alexander-Sat Nemo, and Sergei Ondar.

All uncredited references to shamans, Tuvan or otherwise, are from my field recordings and notebooks.

Parts of this book have previously appeared in print in earlier stages. John Zorn has given permission to reprint parts of Holy Ghost published by Hips Road in ARCANA V, 2010 (appearing in revised form as part of chapter 1). I also draw on the following:

Musicians, Carvers, Shamans,Cambridge Anthropology 25, no. 3 (20052006): 116.

Transcultural Collisions; Music and Shamanism in Siberia, essay published online by the School of Oriental and African Studies, London (September 2007), http://www.soas.ac.uk/musicanddance/projects/project6/essays/file45913.pdf.

On Listening,Perspectives of New Music 48, no. 2 (summer 2010): 152179.

I was in the final stages of writing when news came that Gendos Chamzyryn had died in Kyzyl, Tuva. He was a great musician and friend, and will be sorely missed. He had written to me that he thought people all around the world would be interested in this book.

Tim Hodgkinson

London, June 2015

I Word and Body

1 Prelude

Summer 1996, Ust-Ordinsk, west of Lake Baikal, Siberia: percussionist Ken Hyder and I are on stage; everythings ready, were about to play. I raise my saxophone to my lips. Suddenly I hear a voice. Someone is speakingnot in a hushed way but out loud, addressing everyone in the room, asking a public question: the question is:How did you begin playing music?

NOW? You want to know that NOW? Before even a note?I started to hear certain music,I said,as if it were a window opening into another world, a world that was more vivid than the one I lived in at home with my parents. And that intensity is something Ive always gone after ever since. To lift people up out of where they are, to bring a sense of limitlessness, of possibility, a reminder that that also IS.

These improvised words, part artistic manifesto, part autobiography, bring forward straight away the question of an aesthetics that wishes to concern itself with being. Such an aesthetics can distill itself only out of subjective experience. To unfold this aesthetics is to describe a network of relationships between the accidents and histories of a life and a mind developing and testing its thought in relation to it.

If I had to give that thinking a rough birthdate, I would recall a few weeks in summer 1967 when I lived above the burning ghats on the bank of the Ganges in Varanasi, India, reading, in a hashish haze, books from the Theosophical Library, puzzling over the thought-pictures, and, most of all, the ones in which language was represented by a horizontal line and spirituality by a vertical one. An intriguing separation between communication and consciousness hovered in these diagrams. This way of depicting the sacred seemed to bear in some way on the organization of art. Was music horizontal and communicative like language, or was it vertical and concerned with changes of consciousness like spirituality? At school I had started on clarinet and then switched to saxophone. I was already a big John Coltrane fan, and hearing the