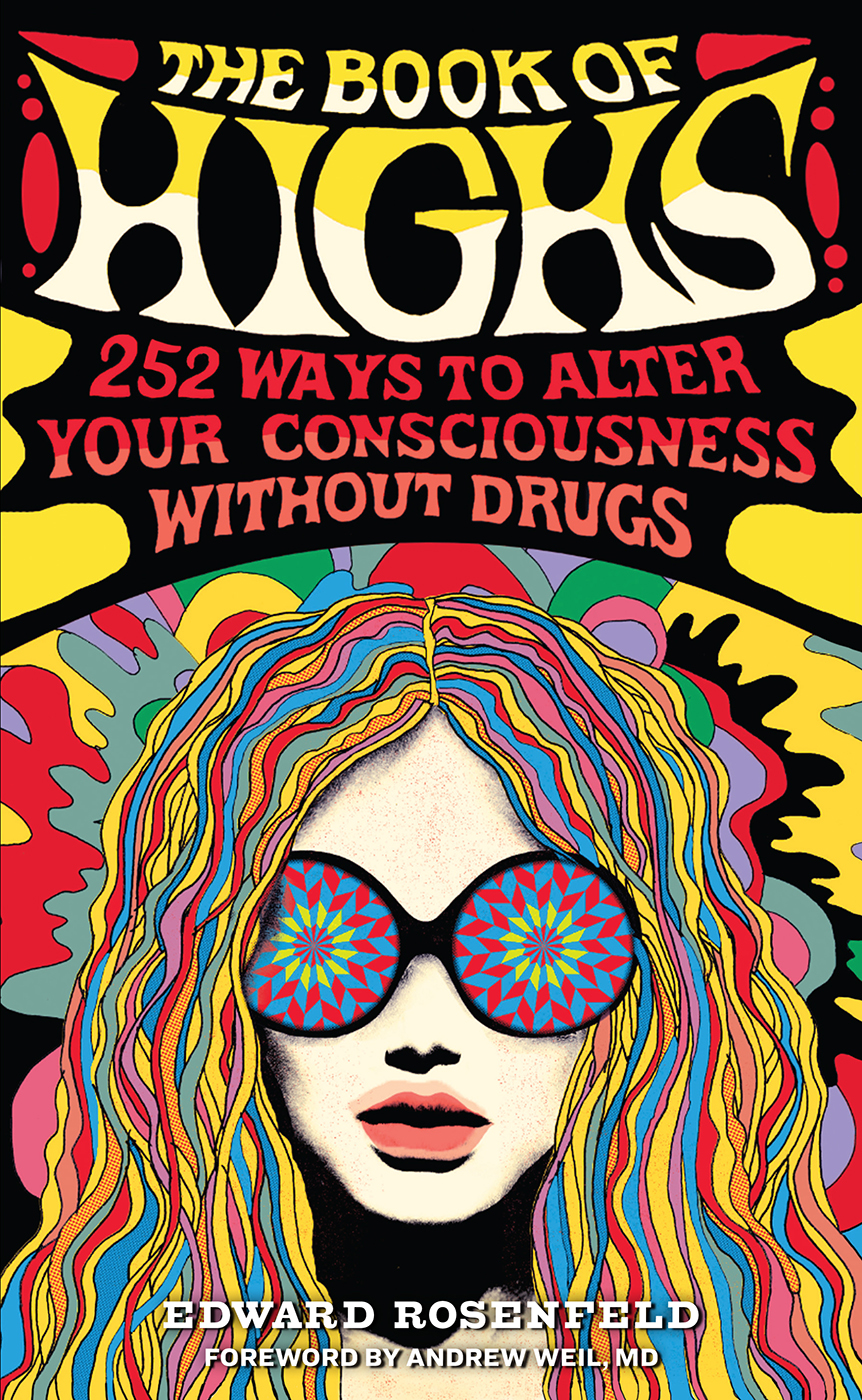

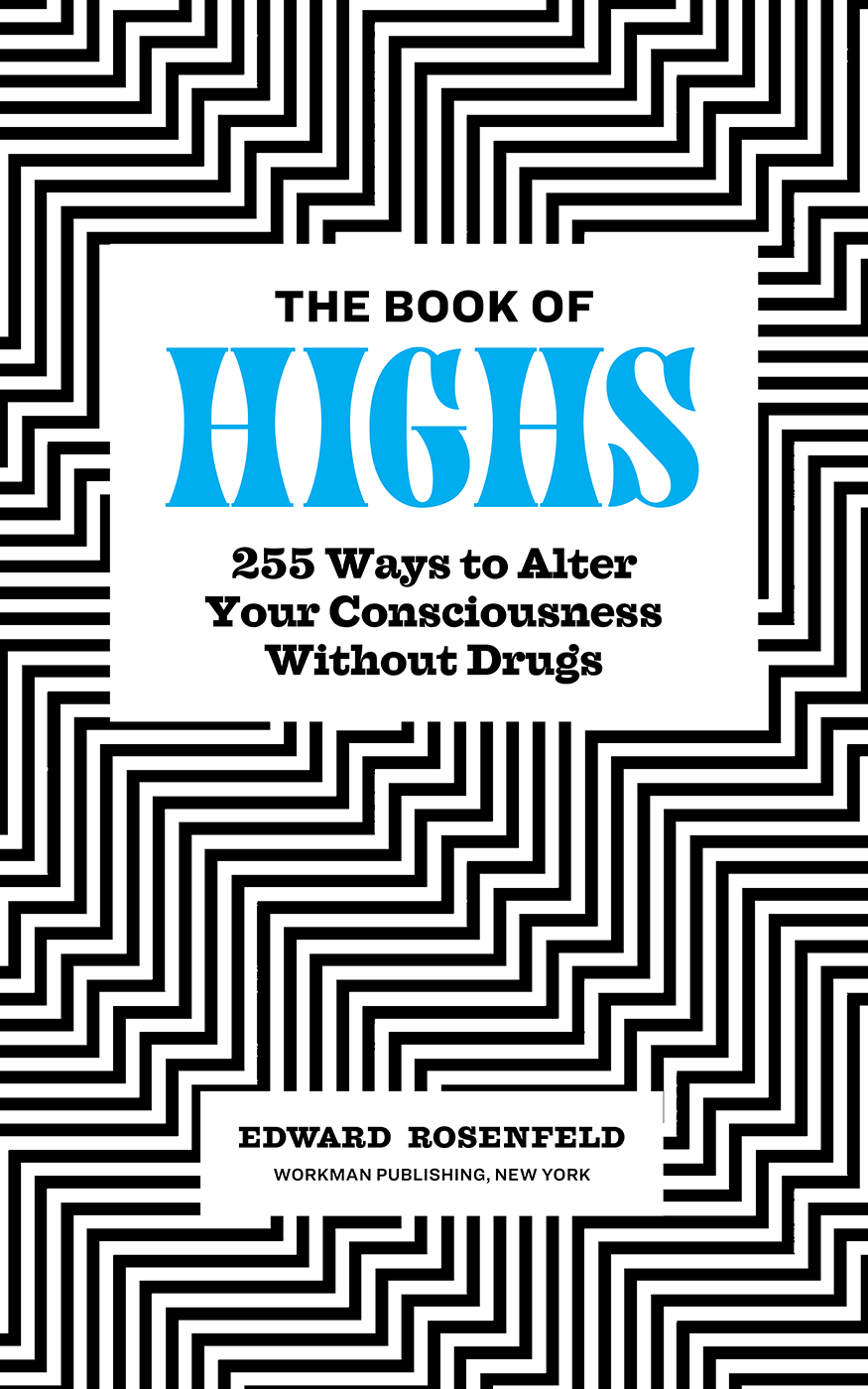

THE BOOK OF HIGHS

255 Ways to Alter Your Consciousness Without Drugs

EDWARD ROSENFELD

1973: to D. & G.-W.

... how hard it is to keep the mind open to surprises!

l. l. whyte in internal factors in evolution

2018: To Sylvia, with all my love and affection.

Acknowledgments

1973: A book of this scope requires the aid of many people. I received much help and guidance. I will attempt to give credit to some; there are numerous others who go unnamed, but not unremembered. The first recognition goes to Frances Cheek, whose idea this was to begin with and who shared that idea so selflessly. My gratitude goes to Bernie Aaronson (and the entire group at the New Jersey Neuropsychiatric Institute), Susan Alexander, Reza Arasteh, Greg Austin, Jeff Berner, Adam Crane, Richie Davidson, Jeremy and the late Rockie Gardiner, Dolly Gattozzi, the late Midge Haber, Harry Hermon, Charles Honorton, the late Mozart and the late Annette Kaufman, Stanley Keleman, Alexandra Kirkland, Stan Krippner, Gay Luce, Eric McLuhan, Ralph Metzner, Marni Miller, the late Gerry Oster, David Padwa, Milo and Celia Perichitch, the late Don Plumley, Ilana Rubenfeld, Pyrrhus Ruches, David Sarlin, the late Steven and Gabriel Simon, Deborah Steinfirst (ne Lotus), Klaus von Stutterheim, John Wilcock, Karl Yeargens, and Gene Youngblood.

Without the very special help of others, this work would never have been possible. Elly Greenberg has typed, endured, and given much-needed support. John Brockman has been a helpful and wise friend. Peter Matsons hard work has made this publication possible. The late Bob Masters, Jean Houston, and Bill Wine shared unselfishly of their own work in the area of altered states of consciousness. Charles Tarts Altered States of Consciousness has been and continues to be an expansive model.

The late Bennett Shapiro provided help, suggestions, and encouragement, as he did tirelessly for more than two decades. The late Marty Fromm gave me and continues to give me the greatest gift of all: myself.

2018: First thanks go to Melissa Mahoney, who found the original The Book of Highs and brought it to her wife, Samantha OBrien, an editor at Workman. Without Melissas sharp eyes and sense, this current edition would not have happened. Thanks go to all the crew at Workman, Bruce Tracy, Suzie Bolotin, and Jean-Marc Troadec, but most especially to Sam, an editor without equal. She has guided, inspired, and nourished this book and helped in every way to make it come to a new life. Thanks so much to you, Sam, for your wonderful professionalism, care, and enthusiasm. Thanks to Kenneth Wapner, my literary agent, for his years of work, support, and encouragement.

Other friends and colleagues spared their time, attention, help, and suggestions. Some provided true inspiration, including Sylvia Rosenfeld, Zachary Rosenfeld and Halley, Elinor Greenberg, Gerd Stern, Neal Goldsmith, Stella Resnick, Helen and Tim Atkinson, Frank Spinelli, Tammy Nelson, Gail Woods and Andrzej Nikonorow, Alexandre Tannous, Karen Azlen; they all deserve credit for their help to me and their contributions to this book.

Contents

Getting High and Staying There

by Andrew Weil, author of The Natural Mind

A ltered states of consciousness have become so respectable in the past few years that they are now known simply as ASCsa sure sign that they are in fashion among scientists. Conferences on them are proliferating (one took place recently at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.), and month by month ASCs carve out a bigger niche in medical literature. But despite the accumulation of scientific data, we still do not know what it is to be high or the significance of our seeking that state so persistently.

The desire to have peak experiences, to transcend the limitations of ordinary consciousness, operates in all of us. It is so basic that it looks like an inborn drive. Almost as soon as infants learn to sit up, they begin to rock themselves into highs. Later, as young children, they learn to whirl into other states of awareness or hyperventilate out of ordinary reality. Still later they discover drugs.

There has been much talk lately of alternatives to drugs. The present book describes a great many techniques for getting high, none of them making use of drugs. If we could teach people other methods to achieve highs, the drug problem would take on more manageable proportions. But what is wrong with drugs? They certainly work for many people, and, if used with the respect and care they demand, are no more dangerous than many agents in common, legal use in our society.

Some object to drug-induced highs on a puritanical level; it is too easy to get pleasure, let alone religious ecstasy, by swallowing a pill. One ought to work or suffer for that reward. I doubt that any drug user will be convinced by such an argument, especially if pills will do the trick. A more convincing argument borne out by the experience of many users is that drugs sometimes do not do the trick. They may trigger panic states and depressions instead of highs. One can take steps to ensure that a drug experience will be good, but there is always a possibility that unforeseen factors will supervene. The drug itself does not contain the experience it triggers. Highs come from within the individual; they are simply released, or not, by the drug, which always acts in combination with expectations and environmentset and setting.

Drugs reinforce the illusion that highs come from external chemicals when, in fact, they come from the human nervous system. The practical consequence of this illusion-making tendency is that users find it hard to maintain their highs: One always has to come down after a drug high, and the down can be as intense as the up. The user who does not understand this may become dependent on drugs because the easiest way to get out of a low following a high seems to be to take another dose of the drug.

I make no distinction between legal and illegal drugs here. Coffee, an innocent beverage in the eyes of many persons, is as dependence-producing as any illegal drug in just this way. The stimulation it provides is offset later by lethargy and mental clouding, usually in the morning. In full-blown coffee addiction a person cannot get going in the morning without his drug, and the more thats consumed, the more the need increases.

Moreover, the more regularly one uses a drug to get high, the less effective it becomes. Many marijuana smokers find that their highs diminish in intensity the more frequently they smoke; chain smokers of weed do not get high at all. Any users of psychedelics, heroin, and amphetamines often look back to their earliest drug experiences as the most pleasureful.

The value of drugs is their ability to trigger important states of consciousness. People who grow up in our materialistic culture may need a drug experience to show them that other modes of consciousness exist. It is notable that the increasingly widespread interest in meditation, intuitive understanding, and spiritual development was spurred by drug-triggered highs giving a glimpse of these other realities. The problem is that drugs cannot be used regularly without losing their effectiveness. They do not maintain highs.

And so there is much searching for other ways of getting high and staying high. Some people say they are looking for more natural methods. But it is difficult to say just what is natural and what is not. Fire walking as practiced in northern Greece may be a terrific high. It is also dangerous when not done correctly; those who try it without proper preparation wind up with badly burned feet. Is it more or less natural than taking mescaline?

Next page