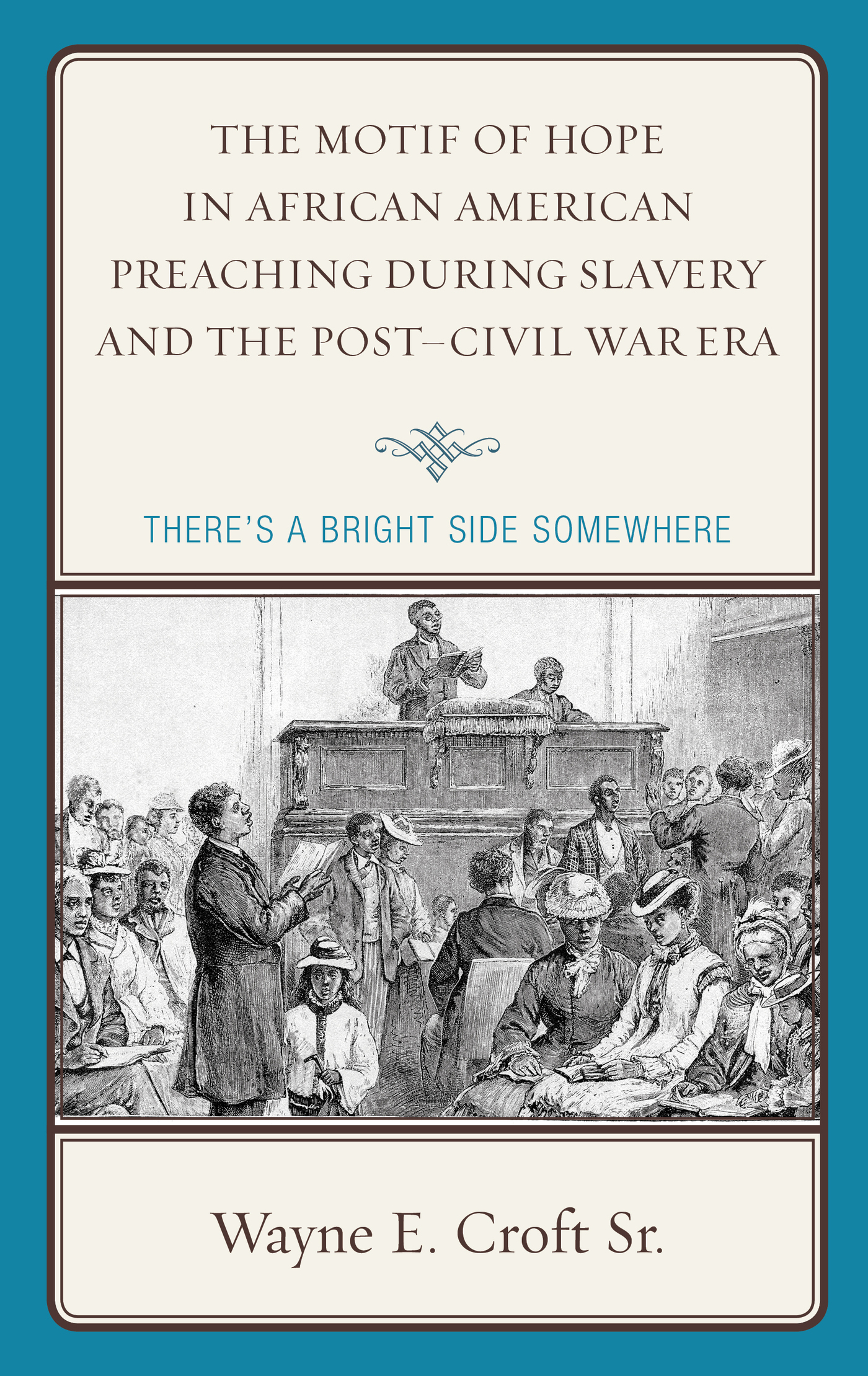

The Motif of Hope in African American Preaching during Slavery and the PostCivil War Era

Rhetoric, Race, and Religion

Series Editor: Andre E. Johnson, University of Memphis

This series explores and examines the intersection of rhetoric, race, and religion. Volumes in this series demonstrate how language both shapes race and/or religion and how race and/or religion shapes the language or rhetoric we use. Scholars examine these phenomena from a historical and contemporary perspective.

Titles in the Series

What Movies Teach about Race: Exceptionalism, Erasure, and Entitlement, by Roslyn M. Satchel

Women Bishops and Rhetorics of Shalom: A Whole Peace, by Leland G. Spencer

The Womanist Preacher: Proclaiming Womanist Rhetoric from the Pulpit, by Kimberly P. Johnson

The Motif of Hope in African American Preaching during Slavery and the PostCivil War Era: Theres a Bright Side Somewhere, by Wayne E. Croft Sr.

The Motif of Hope in African American Preaching during Slavery and the PostCivil War Era

Theres a Bright Side Somewhere

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2017 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4985-3647-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4985-3648-6 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To Lisa,

Her children arise up, and call her blessed;

her husband also, and he praises her

Acknowledgments

This book would have never been completed without God. So, I first and foremost thank God for giving me the strength and perseverance to complete this book. My prayers to God did not go unanswered and the completion of this work is evidence. I further must thank my colleagues the Reverend Drs. Kenyatta R. Gilbert, associate professor of homiletics at the Howard University School of Divinity, Washington, DC, and Frank A. Thomas the Nettie Sweeney and Hugh Th. Miller Professor of Homiletics and director of the Academy of Preaching and Celebration at Christian Theological Seminary, Indianapolis, Indiana. You have encouraged me to continue to be both pastor and scholar. I thank you for your encouragement.

I also thank the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia where I serve as the Jeremiah A. Wright, Sr. Associate Professor of Homiletics and Liturgics in African American Studies. Thanks belong to my colleagues for your support and to the seminary for allowing me to bridge the gap between the church and the academy by allowing me to serve the church and the academy simultaneously.

To my good and dear friend Otis Moss III thank you for your prayers and phone calls during my writing. Whenever we talked on the phone or met face-to-face, Dr. Moss had one question, Did you finish the book? and then said, The world needs it. You helped me persevere.

I want to personally thank Nicolette Amstutz, James Hamill, and Lexington Books for their patience, suggestions, edits, and willingness to publish this book. I am grateful for your interest in this book and your consistent e-mails that kept me moving.

I cannot go without thanking God for my mother, Henrietta Croft, and my father, the late Deacon Rice Croft, for instilling in me love and respect for God. It was, and remains, my mothers powerful prayers and my fathers high admiration for his son and pastor that brought me through. Thanks Mom and Dad for teaching me to trust in the Lord until I die! I also thank my administrative assistant, Minister Carol Jean Hicks, for her suggestions and helping me think through some of my thoughts, and my seminary intern, Nicholas Christian, for assisting me in proofreading the final manuscript. I also thank the wonderful people who make up the St. Pauls Baptist Church in West Chester, Pennsylvania. I thank you for your prayers, love, support, and encouragement. You have allowed me to serve both the church and the academy. Thanks also for allowing me to develop my gifts both inside and outside the church. I am forever grateful!

Finally, but not at all least, I thank my children, Darlene (William), Wayne Jr., Candace Nicole, and my granddaughter Patterson for their love and patience; you are the best. My wife Lisa, words cannot express my gratitude; you are an awesome woman and a wonderful wife. I am well aware that without you and God I would have never made it to this point. Thank you for reading this book in its entirety, and, most of all, for praying me through. This book is not mine alone; it also belongs to you. I love you and will always be grateful to God for entrusting you to me.

Introduction

The subtitle of this book is a well-known Black spiritual. African American spirituals are deeply rooted in black resistance to racism, manifest in ill treatment, poor social conditions, and the like. Spirituals precluded the acceptance of these social injustices because of the strong tones of hope inherent in their central themes. The aforementioned spiritual illustrates the African American quest for hope. This song was sung across America in Black churches at a time when African Americans grew weary but fought to eradicate social injustices. The song encouraged and inspired a people who endured suffering by its words:

Theres a bright side somewhere,

Theres a bright side somewhere,

Dont you rest until you find it,

Theres a bright side somewhere.

This particular spiritual infused African Americans with hope for a better and brighter day. It encouraged them to keep striving and not to rest or accept the conditions until that brighter side was realized. It must be noted that this brighter side was not simply heaven, although at times, heaven was referenced. The religious historian, Miles Fisher, states that heaven for early black slaves referred not only to a transcendent reality beyond time and space, but designated the earthly places that blacks regarded as lands of freedom. Heaven referred to Africa, Canada, and the northern United States.

Although the spirituals and singing have been vital to the African American worship experience, and while this experience is not homogeneous, the preaching moment, for the most part, remains central in many African American worship experiences. The quest for a brighter side or realized hope, was not simply sung by African Americans, but more importantly proclaimed by its preachers. African American preaching attempts to lead an oppressed and marginalized people to a God who sides with the downtrodden and eradicates injustices. What is proclaimed from Scripture about God offers African Americans hope and a liberated life that is to be enjoyed on earth as well as in heaven. Hope that is proclaimed in African American preaching is against injustice and a new order of justice and peace is proclaimed and realized. Thus, I define hope as the anticipation of something better than the here and now. Hope is forward moving, thinking, and believing in spite of ones existential situation. It moves to make what one envisions for themselves, others, and a community a reality.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.