African American Faces

of the Civil War

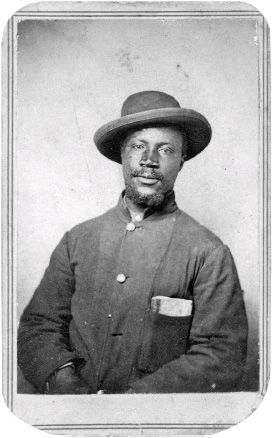

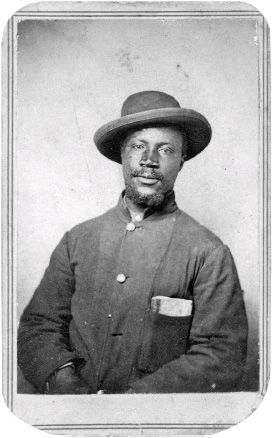

This carte de visite is printed at actual size.

The photographs in this collection have

been enlarged.

African American Faces

of the Civil War

AN ALBUM

Ronald S. Coddington

WITH A FOREWORD

BY J. MATTHEW GALLMAN

2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Coddington, Ronald S., 1963

African American faces of the Civil War : an album / Ronald S. Coddington; with a foreword by J. Matthew Gallman

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-0625-1 (hdbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4214-0723-4 (electronic) ISBN 1-4214-0625-X (hdbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 1-4214-0723-X (electronic)

1. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Participation, African AmericanPictorial works. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Biography. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Portraits. 4. United States. ArmyAfrican American troopsBiography. 5. United States. ArmyAfrican American troopsPortraits. 6. United States. Colored TroopsBiography. 7. United States. Colored TroopsPortraits. 8. African American soldiersBiography. 9. African American soldiersPortraits.

I. Title.

E540.N3C64 2012

973.7415dc23

2012002231

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

The frontispiece photograph, by an unidentified photographer, is from the collection of Sam Small. It depicts Tom Henderson, who acted as a servant to Lt. Col. Charles B. Lamborn of the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 4105166936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

For Anne, always and forever yours

For Mom, with love and gratitude

In memory of my grandmother, Louise Bodnar,

who continues to inspire

Foreword

J. MATTHEW GALLMAN

HISTORIANS ARE FOND OF USING THE NOTION OF A SNAPshot to describe and explain certain historic phenomena. It is a useful expression. A snapshot captures a particular place and time, while revealing little about what is to come or what has gone before. Sometimes the evidence of a moment cannot capture change over time, and we are wise to look at it through this static interpretive lens. Other snapshots might capture a diversity of facts coexisting at that moment, and by focusing on that historic moment, while ignoring what happened after the shutter clicked, we can gain important insights or remind ourselves of things that we should not have forgotten. Historic actors might have had feelings about how events would unfold, but they did not know what would appear on the next page. Even where historians might recognize the preconditions of future events in one moments data, the participants did not necessarily see what was to come. Thus, we now speak of the antebellum decades although nobody in the 1850s used the term, few anticipated war, and none correctly predicted the carnage that would follow. As Gary Gallagher has recently demonstrated in The Union War, even though the Civil War became a war for emancipation and irrevocably changed the racial landscape of the United States, on the eve of the War Between the States the vast majority of white Northerners thought much more about preserving the federal Union than they did about slavery or racial inequalities. As Gallagher reminds us, it is a crucial error to read the emancipation narrative into the war years and antebellum years. A snapshot of 1860 contains many Northern abolitionists but many more people who thought little about the issue. Of course, not everyone was in the same snapshot.

By an interesting coincidence, the Civil War years saw two important turning points in American life. Both transitions are illustrated in the seventy-seven photographs assembled by Ronald S. Coddington in his fascinating volume, African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album. The two narrative threads are quite distinct, but they come together to point to some larger conclusions about the meaning of race and citizenship in mid-nineteenth-century America. It is perhaps not pushing the metaphor too far to suggest that two very distinct historic snapshots come together in these photographs.

The first narrative concerns the roles of African Americans, and particularly black men, in American public life. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, the national debate over slavery had certainly placed racial issues at center stage in political discourse; but in truth, those debates had concerned a fairly narrow array of issues. Some Northerners differed with most white Southerners over the future of slavery in the territories, as well as over the fundamental morality of slavery as a system of labor and of unfree labor as the basis for a political culture. As Lincoln would famously write to Alexander H. Stephens on December 22, 1860, shortly after his election, You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. But the heat of some of these quarrelsand the fact that they would soon lead to bloodshedshould not mask the fundamentally narrow swath of terrain over which these rhetorical battles were being fought. Although radical abolitionists called for the ending of slavery all over the United States, antislavery politicians made no such proposals, and there is no reason to believe that many observers seriously predicted an end to the Souths peculiar institution in the near future.

Meanwhile, free blacks in the Northern and Southern states navigated a world of restricted opportunities and unequal rights. Some African Americans accumulated substantial wealth, and in the South more than a handful became slave owners. Most cities had some semblance of a black elite, populated by editors, ministers, and successful businessmen. The vast majority of free

And it was not as if the march of history was clearly moving race relations in a positive direction. In 1850 Congress passed the notorious Fugitive Slave Act, which added teeth to existing federal laws requiring the return of fugitive slaves. As a consequence, free blacks living in the Northregardless of whether they were in fact escaped slaveshad to be ever vigilant for the arrival of money-hungry slave catchers.

Dred Scott was a startling ruling, and the fact that it disturbed so many contemporary observers is worth contemplating. By denying that African Americans had any rights as citizens, the Taney Court rolled back the clock, undermining progress that had been made in some corners of the North. Nonetheless, free African Americans living in the Northern states in 1860 might reasonably have believed that their status as members of a communityif not their legal status as citizensremained largely contingent on where they were. They also recognized that under no circumstances could they expect to be perceived as political, legal, or social equals by most whites.

Next page