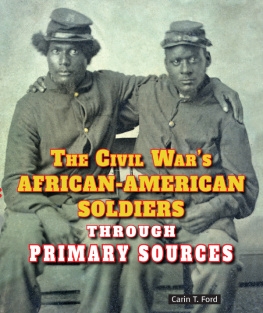

FACES OF THE CIVIL WAR

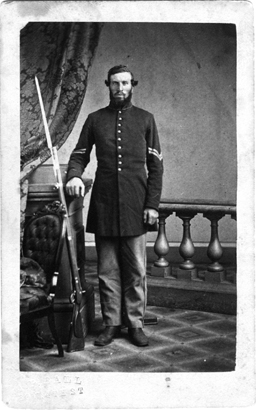

This carte de visite showing an unidentified soldier is printed at actual size. The photographs in this collection have been enlarged.

An Album of Union Soldiers and Their Stories

Faces of the Civil War

R ONALD S. C ODDINGTON

W ITH A F OREWORD BY M ICHAEL F ELLMAN

2004 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2004

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Some of the profiles, in slightly different form, were published in Civil War News between April 2001 and June 2003. An earlier version of the profile of James M. Cooper was published in the September-October 2001 issue of Military Images magazine.

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 212184363

www.press.jhu.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Coddington, Ron, 1963

Faces of the Civil War: an album of Union soldiers and their stories / Ronald S. Coddington; with a foreword by Michael Fellman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 08018-78764 (alk. paper)

1. United States HistoryCivil War, 18611865 Biography. 2. United States HistoryCivil War, 18611865 Portraits. 3. United States. Army Officers Biography. 4. United States. ArmyOfficers Portraits. 5. Soldiers United States Biography. 6. SoldiersUnited States Portraits. I. Title.

E 467.C63 2004

973.7410922 dc22

2003018305

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

The frontispiece photograph was taken by James Presley Ball (18251904) between 1861 and 1863. The unidentified corporals firearm is an Austrian Lorenz musket.

This volume is dedicated to all Americans as a memorial

to our countrymen who volunteered in the armed forces

of the United States during our greatest national crisis.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Michael Fellman

A S N ORTHERN MEN rushed into the Union army after the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, the American correspondent to an English periodical noted, For the few days in which the military are being enrolled, the photographic galleries are thriving: the wise soldier makes his will, and seeks the photograph as possibly the last token of affection for the dear ones at home. And so it was off into the vast, unknown conflict, to possible maiming or death, with the image of the proud and probably fearful new soldier, uniformed and posed in the photographers studio, left behind. This magical representation, at once of the civilian he had been and the soldier he had become, remained with the home folks as they held their breath awaiting news of injury, death, or disappearance.

Into this unusual and moving volume Ron Coddington has gathered the portraits of dozens of ordinary soldiers junior officers and enlisted men rather than the famous generals giving us a portrait gallery of Union soldiers on the brink of a war that would change their lives forever, whatever their physical fate. More than that, he has tracked down the life histories of these men and tells us about their wartime and postwar experiences, their stories often ending in death by battle and disease or from postwar wounds, or continuing in more ordinary ways until death in bed, years or decades later. Although many of these men returned home after the war, others stayed restless, wandering the United States in search of greater opportunities, sometimes with a modicum of success, sometimes without. Although Coddington does not speculate on the psychology of these later lives, it does seem clear from their stories that for many soldiers the wounds of war were by no means all visible.

But the images were. They stemmed from a very common experience, that visit to the photographers studio. By coincidence, just in time for the Civil War, technological and business change made possible the ready supply of cheap graven images that matched the soldiers great demand for some form of symbolic immortality. Democratic portraiture filled the great hunger for self-representation of a democratic and individualist soldiery.

Photography was only twenty-two years old when the war started, but it had rapidly developed from an expensive and difficult technique to one readily attuned to the mass production of inexpensive prints. In January 1839, Louis Jacques Mand Da-guerre announced the discovery that bore his name. By March, the American portrait painter and inventor, Samuel F. B. Morse, who was in Europe to secure patents for his telegraph, had met Da-guerre, learned the process, purchased a camera, and brought the process back home to America, where it immediately spread as a quick method of portraiture. Daguerreotypes were unique pictures, the light being impressed directly on a plate that was the picture itself, and so the price remained relatively higharound $5 at first. By 1850 there were 938 daguerreotypists distributed among the cities and many of the towns of the United States, and the price had dropped to about $2.50 still dear, but clearly low enough to feed a rapidly growing demand.

Photography took a great leap forward in the early 1850s, when collodion technology developed, again mainly in France. The photographer now exposed his camera lens on chemically treated glass plate negatives, with the images then transferred onto ordinary, treated paper, making positive prints. This made possible the reproducibility of inexpensive photographs. And then, in 1854, Adolphe-Eugene Disdri, the court photographer to Napoleon III, developed a movable plate holder, allowing eight to twelve poses to be imprinted on one negative plate. A single print from this negative could thus produce many images, and reproductions were made even cheaper by the fact that unskilled laborers could handle the printing processes. In 1857, according to legend and possibly in reality, the Duke of Parma gave Disdri one of his business cards and asked that his photograph be glued onto the reverse side. As such cards were of a uniform four by two and one-half inches throughout Europe and America, this small portrait, known as the carte de visite, became the standard form of cheap photographic portraits.

Technological and artistic transfer from imperial France to the democratic United States (sometimes via Britain) continued its swift pace. Such trade long had been true of many products, notably Parisian womens clothing fashions. Then as now, Paris was the hub. Not only did wealthy Americans buy directly at Parisian salons, artists from Godeys Ladys Book, the leading American fashion magazine, attended the French showings, and within months French haute couture knock-offs appeared on the streets of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Now the collodion process and the carte de visite photographic reproduction form also spread like lightning, to England, and then across the Atlantic. First advertised in January 1860 by a Broadway photographer as The London Style Your Photograph on a Card, carte de visite pictures cost only $1.00 for 25, and competition soon increased the quantity the customers dollar would buy. What was, even at the time, called cardomania spread like the flu in the Spring of 1860, by which time 3,154 Americans earned their living as photographers, eighty-three in New York alone, and at least one in nearly every city and town.

Within a year the newspapers were advertising another new product photograph albums; between 1860 and 1865, fifteen styles were patented. Most versions featured recessed pockets with slots for inserting the pictures. Some albums were ornate, costing up to $40, some priced as low as $1.50. Photographers mass-produced landscapes and pictures of famous people in the

Next page