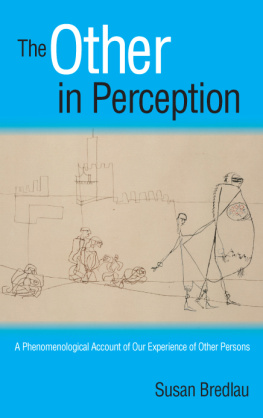

SITES OF EXPOSURE

STUDIES IN CONTINENTAL THOUGHT

John Sallis, editor

Consulting Editors

Robert Bernasconi | James Risser |

John D. Caputo | Dennis J. Schmidt |

David Carr | Calvin O. Schrag |

Edward S. Casey | Charles E. Scott |

David Farrell Krell | Daniela Vallega-Neu |

Lenore Langsdorf | David Wood |

SITES

of

EXPOSURE

ART, POLITICS,

and

THE NATURE OF EXPERIENCE

JOHN RUSSON

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by John Russon

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-02900-3 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-02925-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-02941-6 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18 17

For Shannon Hoff, a committed and original philosophical thinker and a wonderful person with whom to share experiences

By one river it divides two lands.

Gallus, fragment 1

Those who listen to the word then follow the best of it; those are they whom Allah has guided, and those it is who are the men of understanding.

The Holy Quran, Chapter 39, Verse 18

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

JILL GILBERT is responsible for me writing this book, and I am grateful to her for challenging me to do so while she was writing her doctoral dissertation. I wrote almost the entire book at I Deal Coffee, on Ossington Avenue in Toronto, sitting across the table from Shannon Hoff, to whom this book is dedicated and to whom I offer my thanks for ongoing companionship, for talking through the ideas, and for reading the manuscript. I learned most of what I know about the ancient Greeks from Patricia Fagan; Luis Jacob and Kirsten Swenson are largely responsible for my knowledge of contemporary art and Philip Sohm for my knowledge of Renaissance painting. I am deeply grateful to each of these remarkable individuals for the ways in which they have enriched my life by sharing their passionate commitment to their fields and by their friendship. I am grateful as well to many friends and colleagues who were very helpful to me while I worked on this book and in my studies in generalmost notably Pravesh Jung and Siby George at IIT-Bombay; Prasenjit Biswas and Xavier Mau at NEHU in Shillong; mer Aygn at Galatasary University in Istanbul; Kirsten Jacobson at the University of Maine; Kym Maclaren and David Ciavatta at Ryerson University; John Sallis at Boston College; Caren Irr at Brandeis University; Gregory Nagy at Harvard University; John Lysaker, John Stuhr, Susan Bredlau, and Andrew Mitchell at Emory University; Galen Johnson at the University of Rhode Island; Mark Munn at Pennsylvania State University; Matthew Ratcliffe at the University of Vienna; Phil Hutchinson at Manchester Metropolitan University; Greg Kirk and Joe Arel at Northern Arizona University; Scott Marratto and Alexandra Morrison at Michigan Technological University; Jay Lampert and Eva Simms at Duquesne University; Whitney Howell at LaSalle University; Laura McMahon at Eastern Michigan University; Jason Wirth at Seattle University; Jing Long at Jilin University; Evan Thompson at the University of British Columbia; Bob Sweetman at the Institute for Christian Studies; David Morris at Concordia University; Ral Fillion at Laurentian University; Peter Simpson, Director General of the Canadian Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service; and Victor Bateman, John Burbidge, Ray Cleveland, Charlie Cooper-Simpson, Maliheh Deyhim, Eli Diamond, Nick Fraser, Ali Karbalaei, Adam Loughnane, Bronwen Mc-Cann, Jeff Morrisey, Graeme Nicholson, Belinda Piercy, Brian Rogers, Kenneth L. Schmitz, Abe Schoener, Jacob Singer, and Bill Smith. Reproducing artworks can be complicated logistically, and so I also wish to thank all the individuals and institutions I worked with in securing the images used in this book and the permission to reproduce them, the details of which are found in the figure captions; I am especially grateful to Karen Reichenbach of Artangel in London, Carolyn Cruthirds of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Bart de Sitter of the Royal Museum of Fine Art in Antwerp, and Tracy Mallon-Jensen of the Art Gallery of Ontario, each of whom was exceptionally nice and helpful. I am also grateful to Dee Mortensen for her help and support in making possible the publication of this book and to Gail Naron Chalew, whose careful copy-editing of the manuscript resulted in many improvements.

SITES OF EXPOSURE

Introduction

IT IS SOMETIMES difficult to introduce one person to another. The difficulty lies in finding a description that seems true to the person. We want to express her life and personality, but we settle for a name and some stale, superficial descriptions: This is Judith, from Montreal. Shes a geography major at Concordia, and shes a good friend of Mei. Ultimately, we want to communicate what it is like to know this person and how she makes something exciting and unique out of her engagement with the world, but our sentences cannot really convey that. Instead, they simply list static features, intended to spark interest. Indeed, what we really want to say is You should get to know her: it is only through living interaction with her that our friend can truly reveal herself, and we make our introductions to facilitate such an interaction. The introduction, in other words, is not meant as a true portrayal, but only as a prompt to draw another person in and as an exhortation for the two to engage with each other; it is be discarded as quickly as possible in favor of actual immersion in dialogue.

Introducing a work of philosophy poses similar difficulties. Like another person, a work of philosophy is not a static assembly of facts, but is something with which one must develop a personal relationship: it is only philosophy if it speaks directly to you. Like another person, philosophy is something that can change one, and, also like a person, it is something that can reveal its meaning only in and through ones interaction with it: the meaning of the work cannot be adequately portrayed in advance or in a series of superficial descriptions, but will reveal itself only through ones immersion in it, only through ones allowing it to show itself on its own terms.

And so, although I want here to lead you into this book, I nonetheless hope you will quickly discard this introduction. My intention is to outline briefly a few ideas that will spur you to read the book and will give you a reasonable sense of what you will encounter by reading it. I do not, however, want to undermine the possibility of the book revealing itself to you in its own way, as the trailers for Hollywood movies sometimes do when they reveal in advance too much about the movie, making it impossible for the film to deploy its own narrative powers to lead you into the mystery and excitement of its subject. My real hope is simply that you will turn as quickly as possible to and start reading.

Next page