Authors note

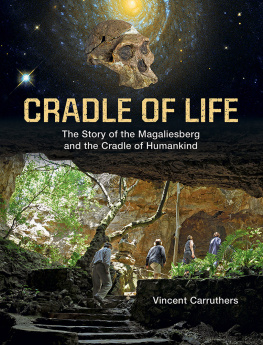

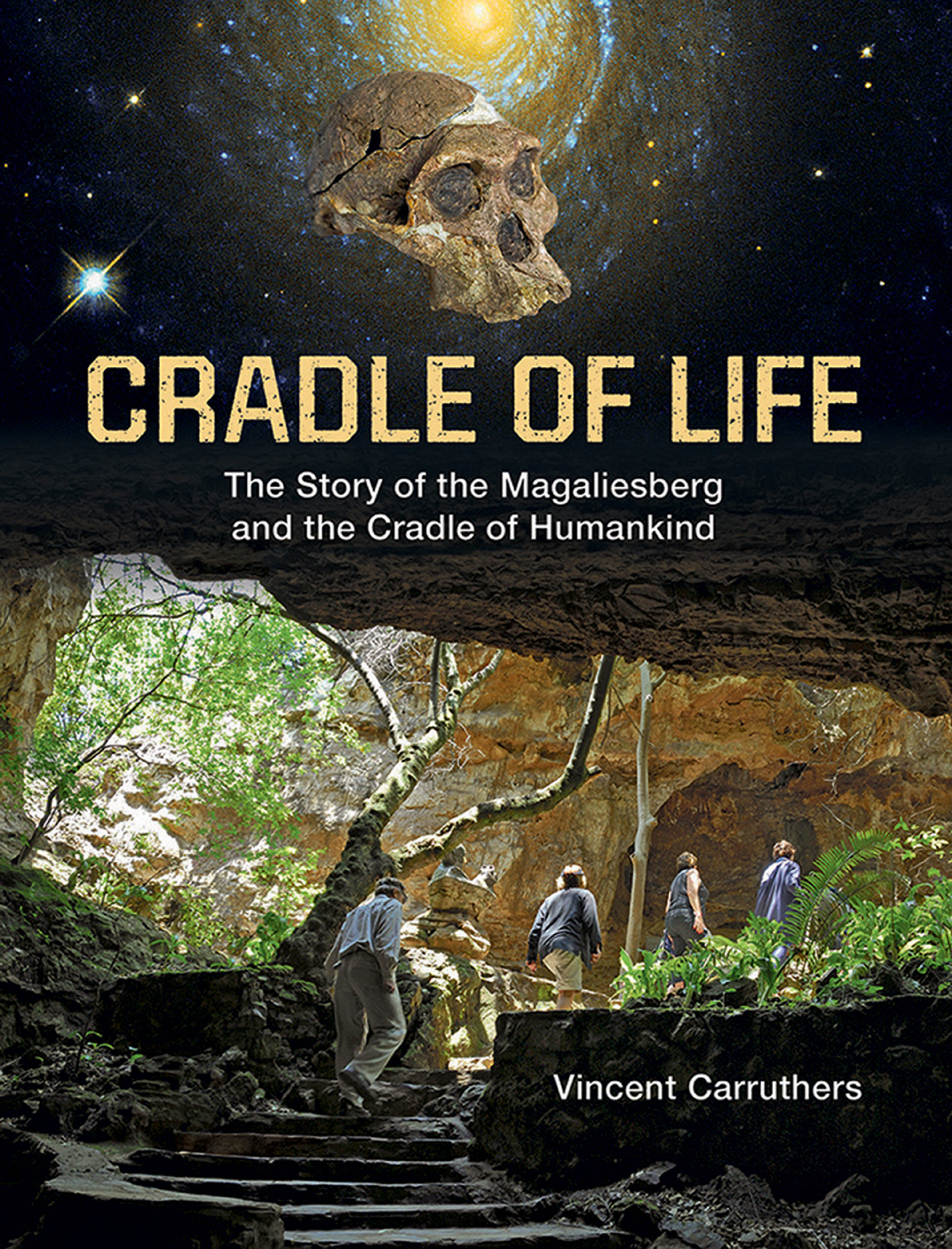

For many years I have been intrigued by the area now known as the Magaliesberg Biosphere Reserve. Here, close to the throbbing cities of Johannesburg and Tshwane/Pretoria, lies the evidence of the long and complex story of the origins of life not only the hominin fossil record for which it is most famous, but the entire evolution of our living environment. I have derived a life-long pleasure from hiking, observing, reading and working professionally in this rocky countryside and, from the generously shared expertise of others, I have learned to enjoy and respect its magnetic charm. Over the years, I have tried to convey some of that fascination in talks and in other publications about the Magaliesberg and I hope to do so further in this work by exploring the full evolutionary history revealed in this landscape.

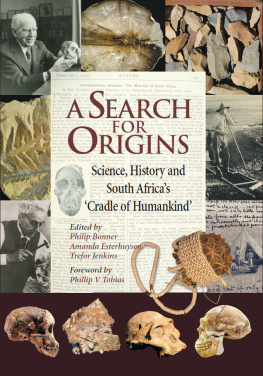

Many people have helped to make my pursuit of the story of the Cradle-Magaliesberg such a rewarding experience. There have been adventurous field trips, interesting discussions over long Sunday lunches and hikes along winding paths with wonderful friends. Tim Partridge and Tony Brink introduced me to the unique geomorphology, and the ever-cheerful Phil Bonner shared his unequalled knowledge of the history of the people of the Cradle. Revil Mason was the first to show me the archaeological richness of the region in the 1970s, and Lee Berger fired my enthusiasm for palaeoanthropology a decade later. Kevin Gill taught me about the botany and Paul Fatti encouraged me to join the Mountain Club of South Africa as part of their dedicated defence of the environment. At the time of the centenary of the South African War, I accompanied John Pennefather and the Rustenburg Military History Group on some wonderfully informative field trips to the battlefields in the Magaliesberg area, and the history of that war has become an abiding interest of mine.

With the emergence of a new political dispensation in South Africa in the 1990s, opportunities arose to broaden the heritage estate of the country and make it more inclusive. I was privileged to participate in the consulting teams that prepared plans for the Cradle World Heritage Site and associated developments. On those projects I worked alongside and learned a great deal from colleagues who were archaeologists, palaeontologists and environmental lawyers with prodigious knowledge of the Cradle region. Other assignments brought me into contact with landowners of the area, and some favourite times were spent on the properties of Prospero Bailey, John Nash and his family, Mark and Christine Read, Hennie Joubert, and owners of the Rhenosterspruit Conservancy, all of whom were embracing the World Heritage Site concept in the early 2000s.

In 2004, Belinda Bozzoli, then Deputy Vice-Principal Research of the University of the Witwatersrand, invited me to work with Neville Passmore of the Skye Foundation to help develop plans for the newly established Institute for Human Evolution (IHE) and to define terms of reference for its director. Seven years later the university amalgamated the IHE with the Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research and I was again asked to prepare plans for the emergent Evolutionary Studies Institute (ESI). These projects were among the most instructive assignments of my career and I benefitted enormously from the discussions I had with scientists, administrators and funders.

While serving on the North West Parks and Tourism Board during that time, I became increasingly concerned that the legislation intended to protect the Magaliesberg was often flouted and irreversible damage was being done. In 2006 I got together with a group of enthusiasts to have the entire Cradle-Magaliesberg region registered by UNESCO as a Biosphere Reserve. The group, which included Paul Fatti, Belinda Cooper, Kevin Gill, John Wesson, Mercia Komen, Anthony Duigan, Andrew Cauldwell and Paul Bartels, was backed by the Magaliesberg Protection Association, the Mountain Club of South Africa and the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa. For a decade we shared difficult but rewarding experiences and I greatly value their friendship and their perseverance, which ultimately resulted in the proclamation of the Magaliesberg Biosphere Reserve in Paris in June 2015.

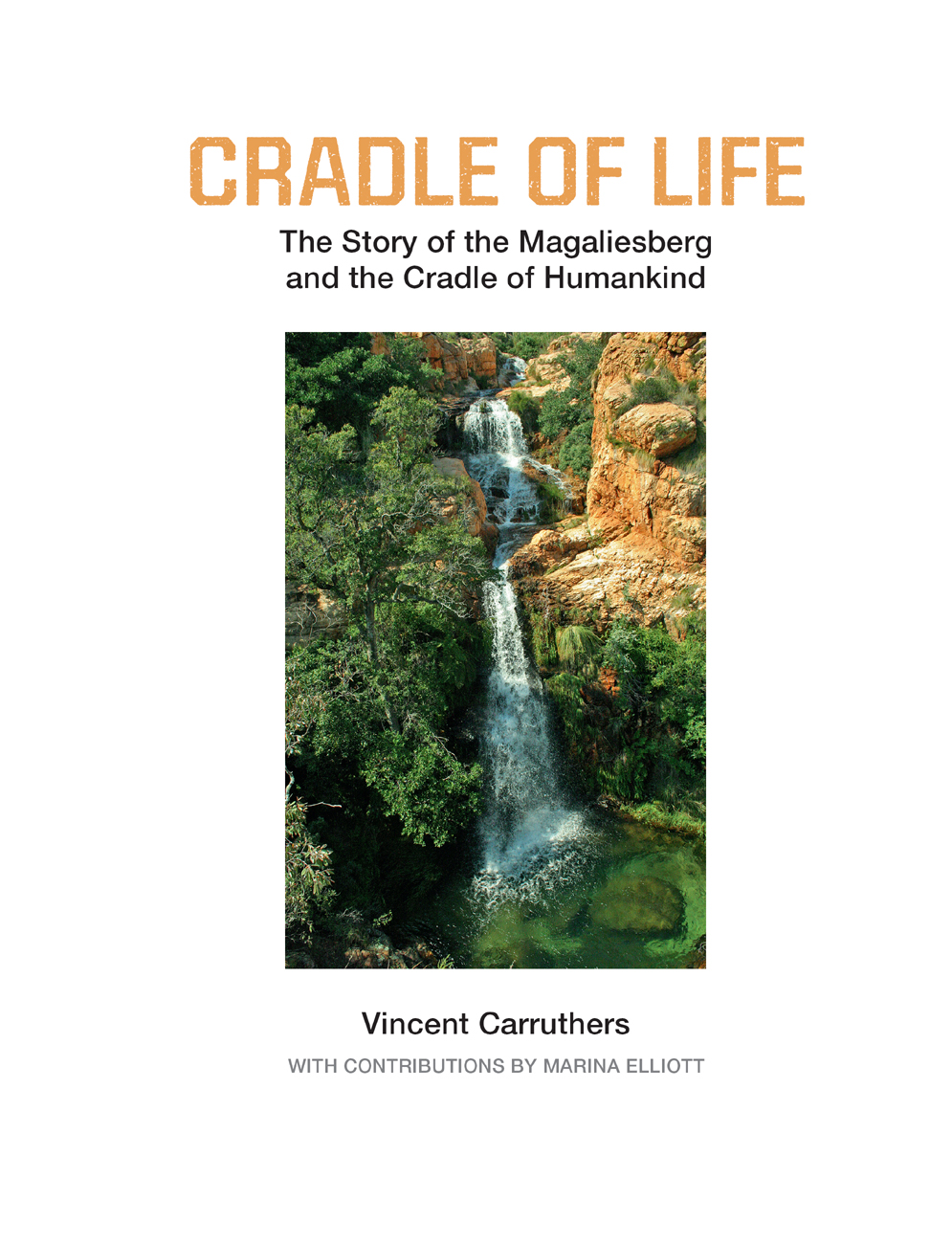

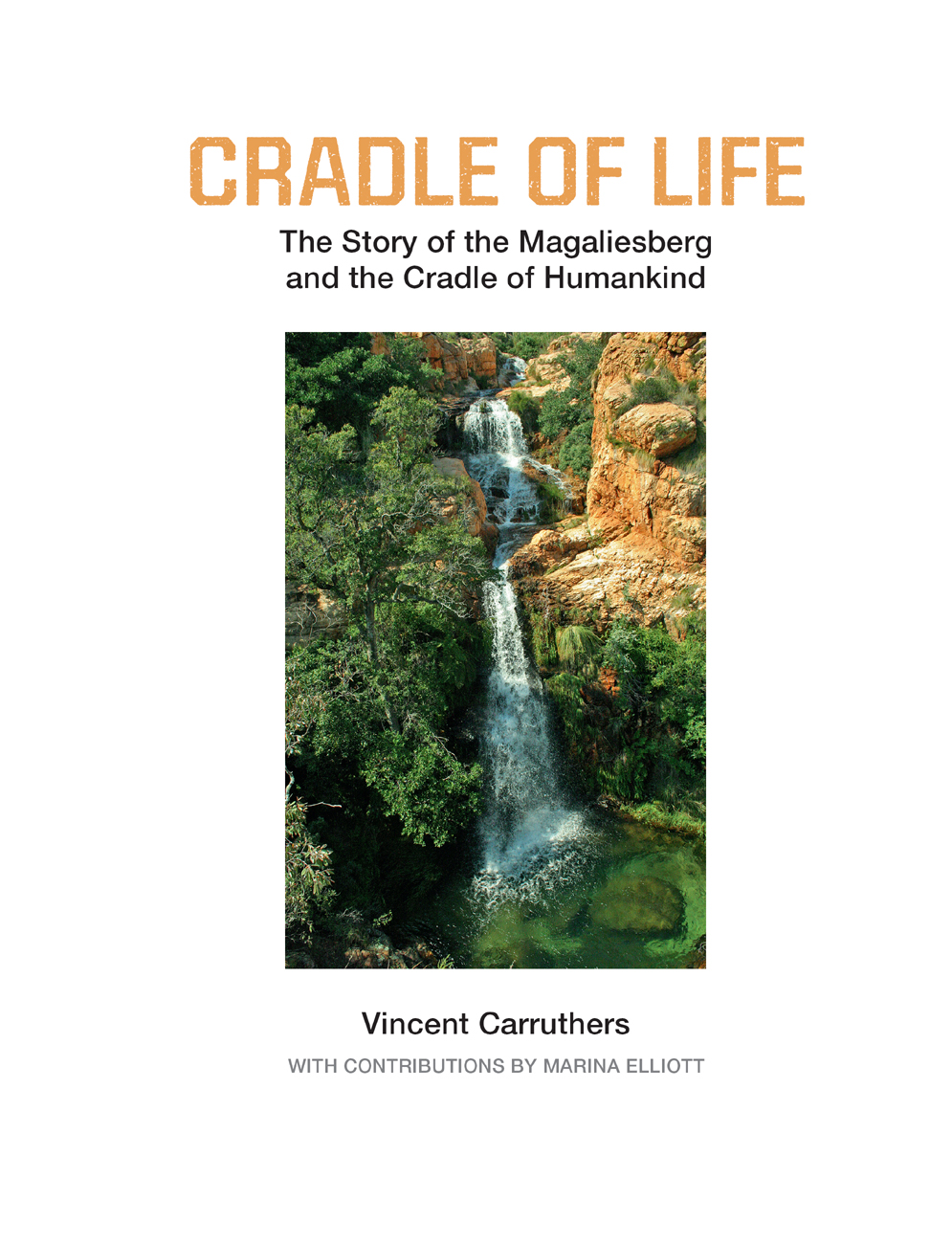

The view from the authors property in the Magaliesberg where his lifelong interest in the region was first kindled.

Acknowledgements

I have drawn information from many sources, and I would like to express my appreciation to the many scholars and authors whose publications have been used and are listed at the end of the book.

I have also been particularly privileged to have had the assistance of some of the most authoritative experts in their respective disciplines. They have given their time and expertise most generously and I am deeply indebted to them for their substantial contributions:

Dr Marina Elliott, leader of the team that recovered the now famous Homo naledi fossils, provided extensive information for the palaeoanthropological chapters, and her unique experience, knowledge and many photographs are much appreciated.

L. Mulligan

Dirk van Rooyen

Professor Ron Clarke, discoverer of the famous Little Foot skeleton, reviewed parts of the manuscript and added considerably to their accuracy. His assistance was particularly generous as it was given while he was at his busiest completing the publication of his own work.

Professor Kathleen Kuman, leading authority on the Early Stone Age in the Cradle-Magaliesberg, gave me a clearer understanding of that critically important tool-making phase of human evolution and provided excellent images.

Professor Tom Huffman greatly improved my knowledge of pre-colonial society and the Iron Age his special field of expertise and gave access to photographs held by the Wits Department of Archaeology.

Professors Morris Viljoen and Richard Viljoen, two of South Africas most eminent geologists, gave invaluable advice and guidance that significantly enhanced the geology sections of the book.

Marion West