A SEARCH

FOR

ORIGINS

Published in South Africa by:

Wits University Press

1 Jan Smuts Avenue

Johannesburg

2001

http://witspress.wits.ac.za

Entire publication Wits University Press 2007

Foreword, introductions and chapters individual authors 2007

First published 2007

ISBN 978-1-86814-418-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holders.

Edited by Karen Press

Picture edit by Sally Gaule

Layout and design by Abdul Amien, Cape Town, South Africa

Printed and bound by Paarl Print, Paarl, South Africa

CONTENTS

| Phillip V Tobias |

| Philip Bonner |

| Saul Dubow |

FOSSILS AND GENES: A NEW ANTHROPOLOGY

OF EVOLUTION |

| Trefor Jenkins |

| Kevin Kuykendall and Goran Strkalj |

| Kevin Kuykendall |

| Himla Soodyall and Trefor Jenkins |

| Marion Bamford |

| Amanda Esterhuysen |

| Amanda Esterhuysen |

| Lyn Wadley |

| David Pearce |

| Philip Bonner |

| Thomas N Huffman |

| Simon Hall |

| Jane Carruthers |

| Philip Bonner |

| Philip Bonner |

| Phillip V Tobias |

| Vincent Carruthers |

| Tim Clynick |

| Philip Bonner, Amanda Esterhuysen and Trefor Jenkins |

FOREWORD

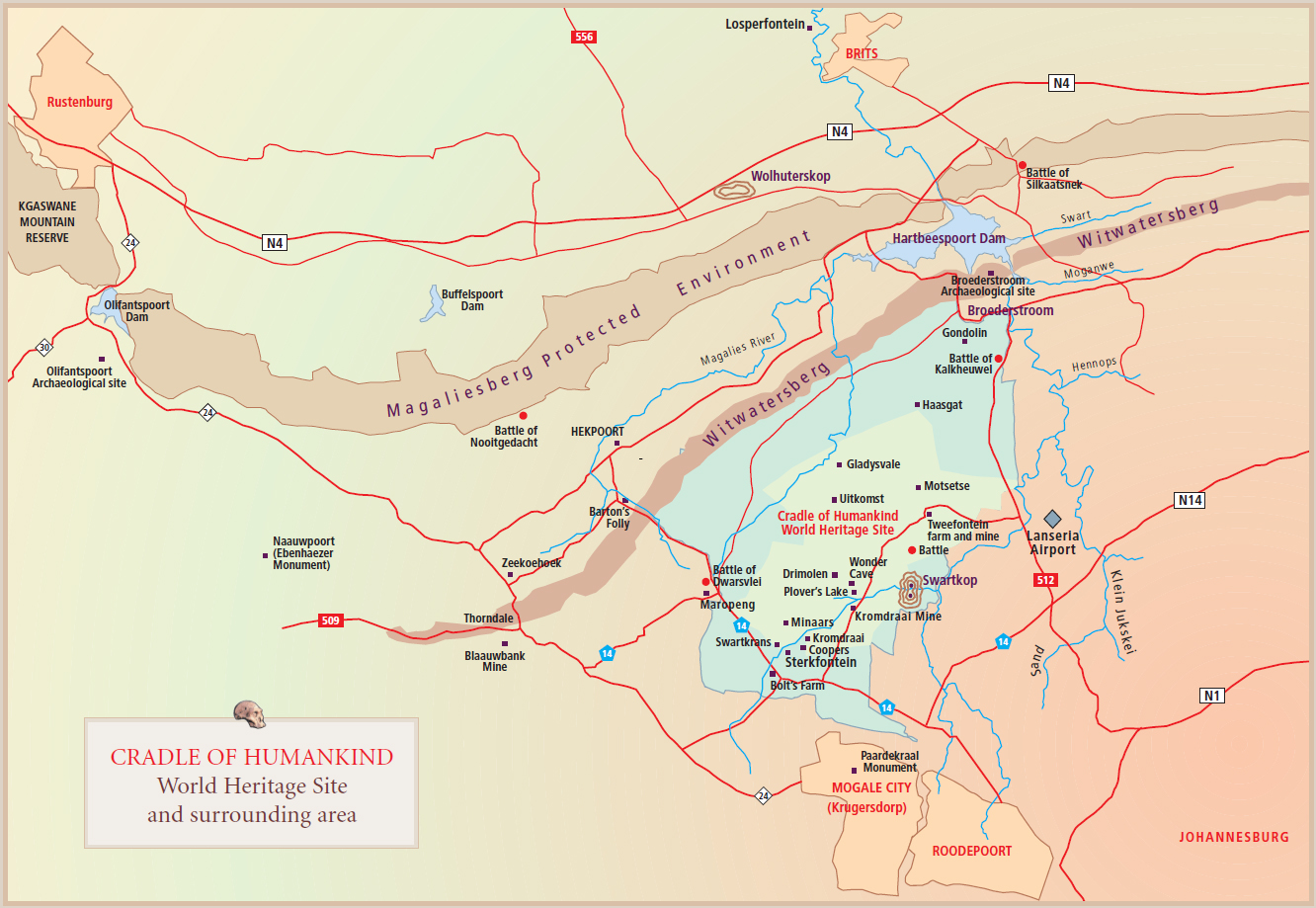

THE DEEP ROOTS OF HISTORY AND PREHISTORY AROUND STERKFONTEIN, SOUTH AFRICA

Phillip V Tobias

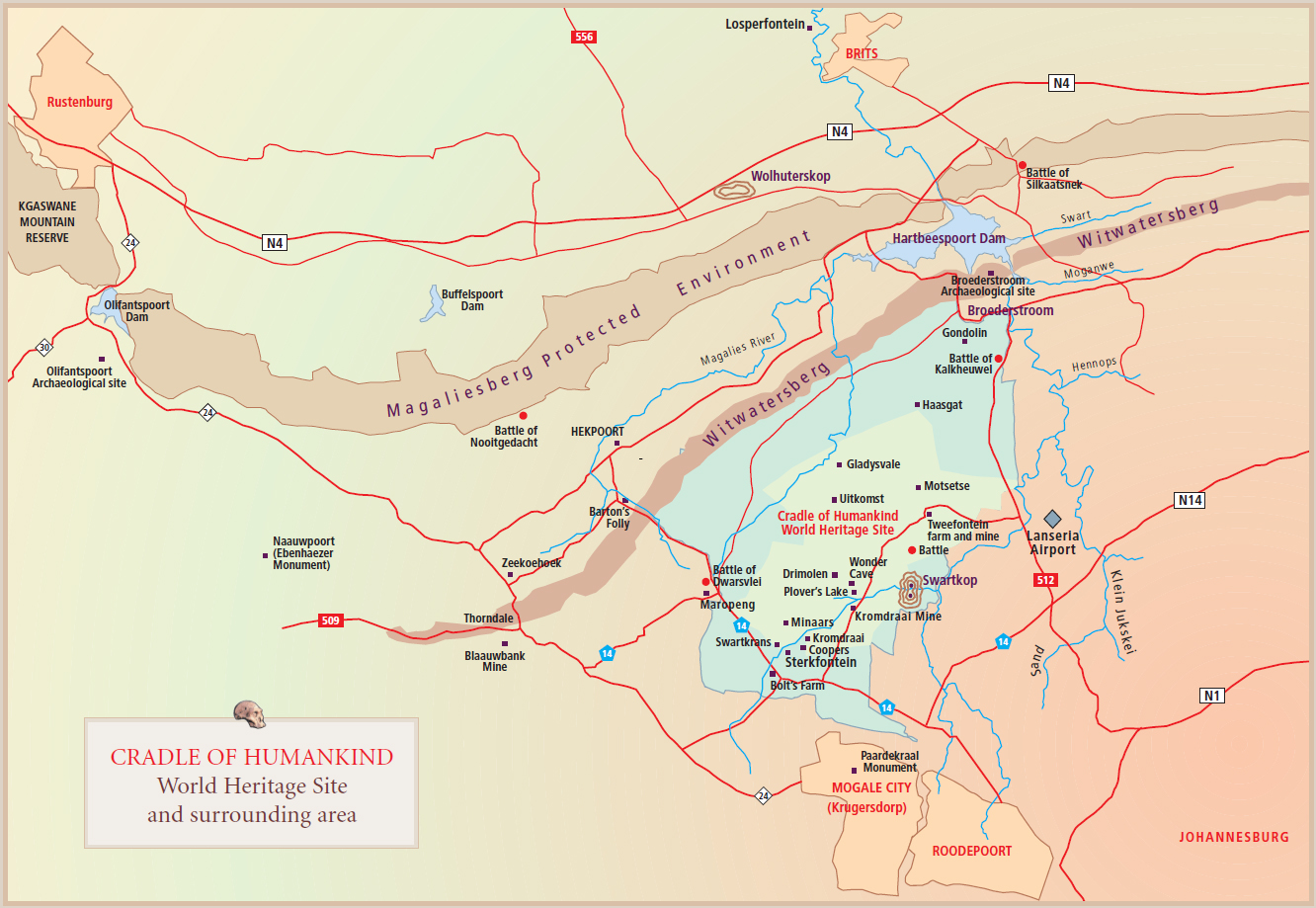

The need for this book has arisen from the listing as a World Heritage Site of the Fossil Hominid Sites of Sterkfontein, Swartkrans, Kromdraai and the Environs popularly though not entirely accurately called the Cradle of Humankind! The World Heritage Centre falls under UNESCO, that is, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. So, to understand the roots of this book, it is necessary to explore South Africas relations with UNESCO and the events leading up to the listing of this countrys first World Heritage Site in 1999.

Although South Africa was a founder member of UNESCO in 1946, it saw fit to withdraw from the Organisation in 1956, when the apartheid policies of the Union government were rising to a crescendo of racial intolerance and discrimination. With the perspective of hindsight, there is no doubt that it was UNESCOs vigorous programme against racism that was the cardinal factor in South Africas decision to withdraw from the Organisation. A resolution adopted at the Fourth General Conference of UNESCO in 1949 called on the director-general, Dr Jaime Torres-Bodet, an esteemed Mexican poet, to (1) collect scientific materials concerning problems of race; (2) give wide diffusion to the scientific information collected; and (3) prepare an educational campaign based on this information. UNESCO in its early years embarked on the preparation of two sets of important publications, The Race Question in Modern Science and The Race Question in Modern Thought. Collectively these books constituted a scholarly and powerful indictment of racism (or racialism, as it was then still called). They were published less than a decade after the horrors that had been perpetrated during the Second World War in the name of race.

Torres-Bodet convened a Committee of Experts on Race Problems. These individuals were drawn from the fields of physical anthropology, sociology, social psychology and ethnology. Their deliberations led to the 1950 UNESCO Statement on Race (Paris, July 1950). This First Statement on Race opened with the ringing affirmation: Scientists have reached general agreement in recognising that mankind is one: that all men belong to the same species, Homo sapiens. The statement went through several subsequent revisions, the Second Statement appearing in Paris in June 1951; the Third in Moscow in August 1964 (when I was invited by the World Health Organisation to be its representative on the Committee my own book entitled The Meaning of Race having been published in Johannesburg in 1961, to be followed by a revised and enlarged second edition in 1972); and the Fourth Statement produced by a Committee of Experts on Race and Racial Prejudice in Paris in September 1967. Towards the end of the century there was a move for a further revision in the light of newer research, and once more I was involved in these discussions.

The 1950 and 1951 Statements on Race affirmed concepts diametrically opposed to the beliefs and policies of the South African apartheid government, which had come to power in 1948. The latter could not tolerate its citizens being exposed to such subversive, communistic and liberalistic information as was emanating from UNESCO. The Union of South Africas complaints against UNESCO included (1) UNESCOs race policies; (2) various requests by UNESCO to send missions to the Union; (3) misrepresentation of the Unions policy in UNESCO pamphlets; and (4) a negligible return received from the Unions financial contribution. There were protracted negotiations. Then South Africas ambassador in Paris gave notice on 31 December 1956 of his governments intention to withdraw from the Organisation. This fateful decision took South Africa out into obscurantist and Stygian isolation and there the country remained for close on forty years.

Among the UNESCO programmes to which South Africa was thereby denied access was the World Heritage Centre and the listing in it of sites, natural and cultural, deemed to be of outstanding universal value. That initiative was adopted by UNESCO in 1972. By the time President Nelson Mandelas democratic government took South Africa back into UNESCO, some 500 sites around the world had been listed, but alas, pitifully few in Africa and none in South Africa.

By 1994 I had been in charge of the excavation of the Sterkfontein cave for close on thirty years. During this time my assistants and I (especially Alun Hughes, David Molepole, Nkwane Molefe, Stephen Motsumi, Isaac Makhele, Hendrik Dingiswayo, Solomon Seshoene and, latterly, Ronald Clarke, Abel Molepole and Lucas Sekowe) had extracted many tens of thousands of vertebrate fossils. These were mainly of mammals, but also of birds, reptiles and amphibians, as well as fossil plants. A remarkable group among the mammalian fossils was that of fossil primates, comprising essentially cercopithecoids (baboons and monkeys) and hominids (members of the family of humankind). The hominids were especially significant. They fell into two or three species, mostly into Australopithecus africanus

Next page