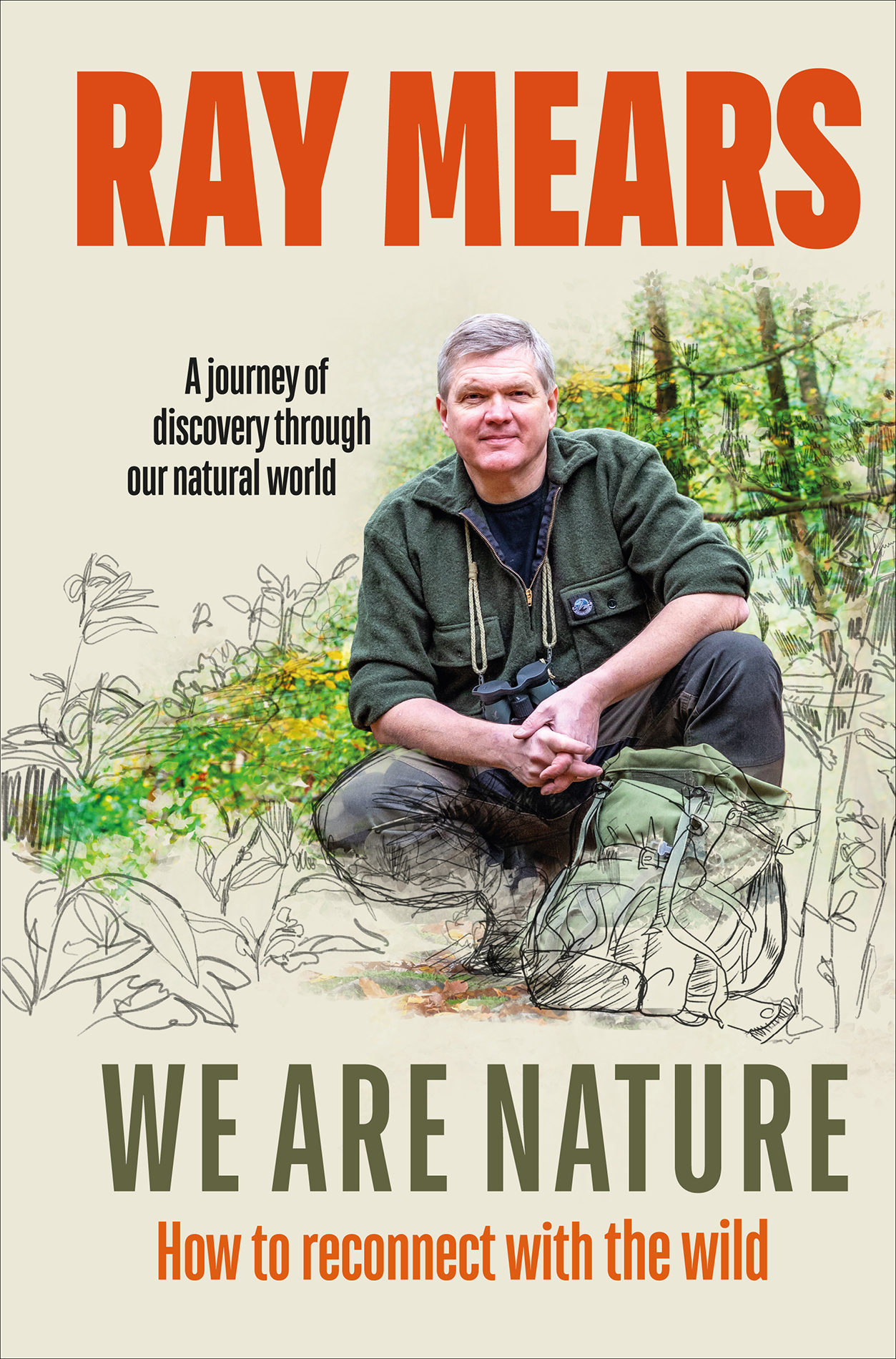

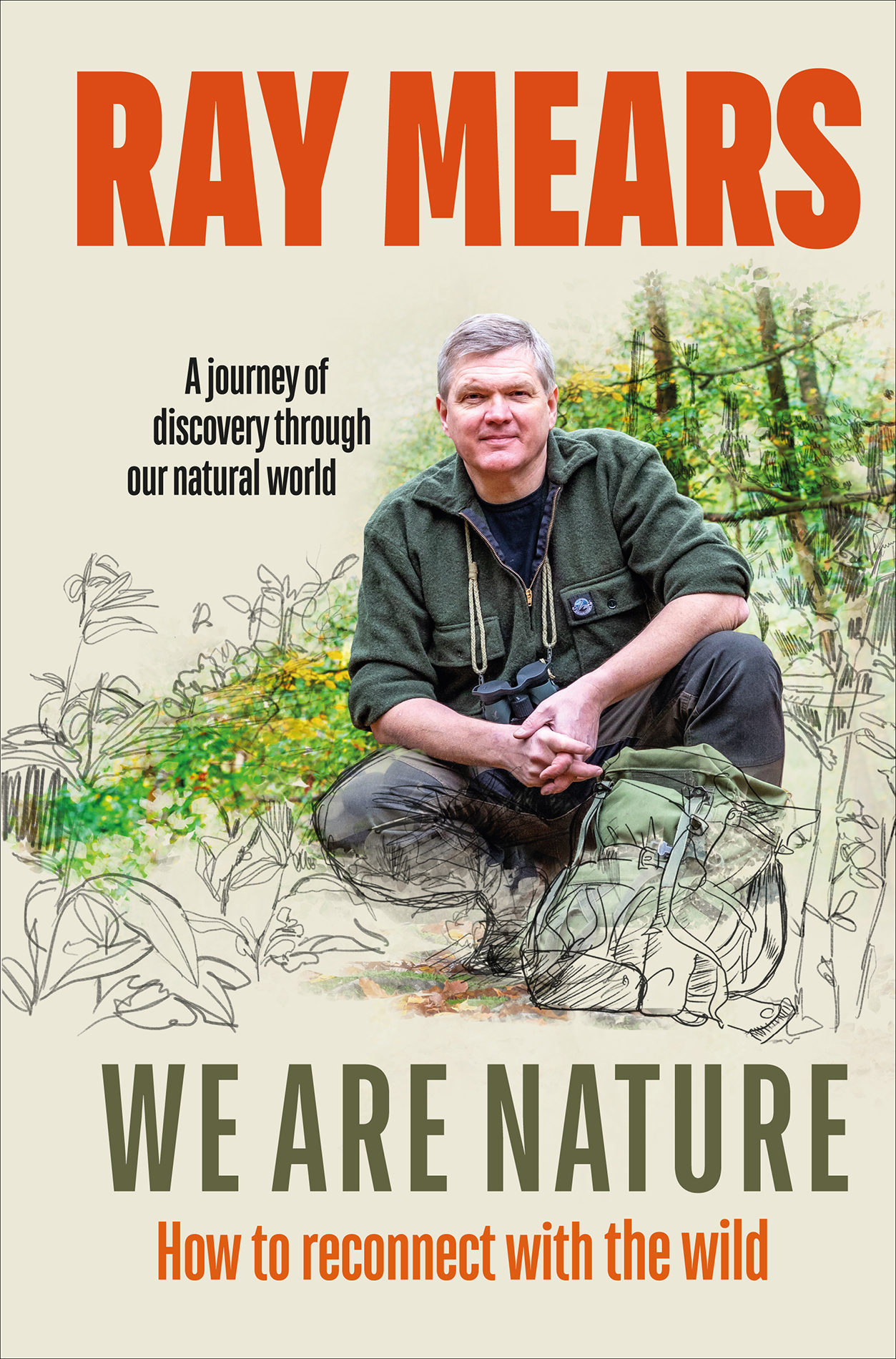

Ray Mears

WE ARE NATURE

How to Reconnect with the Wild

Contents

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

TV presenter, instructor and bestselling author Ray Mears has become recognised throughout the world as an authority on the subject of bushcraft and survival. TV series including Ray Mears Bushcraft, Ray Mears World of Survival, Extreme Survival and Ray Mears Goes Walkabout have made him a household name over the past two decades, but he has spent his life learning these skills, and founded Woodlore, The School of Wilderness Bushcraft, over thirty-five years ago. He was awarded the RGS Ness Award in 2003 and the Mungo Park Medal in 2009. This is his fourteenth book. He lives in Sussex with his wife and stepson.

For Ruth

Thank you for your unwavering love and support.

Darling, you are the most incredible force of nature,

but not even you can call YOO HOO! to sleeping lions.

Footprint of an alpha-male grey wolf, cast in dental stone on 1 May 2009 in the Sawtooth Mountains, Idaho, three days before their controversial delisting as an endangered species.

INTRODUCTION

The Wolf

The old Lakota was wise. He knew that mans heart, away from nature, becomes hard; he knew that lack of respect for growing, living things soon led to lack of respect for humans too.

Chief Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle

Like many travellers, I have over the years amassed an eclectic collection of mementos, reminders of people, places and experiences lived. There is for example a representation of a honey ant, hand moulded in spinifex resin by an elderly Pitjantjatjara Aboriginal woman. We had travelled in the desert together collecting honey ants and witchetty grubs. Her dreaming was honey ant, so she had a special connection with and duty of care for honey ants. In an extraordinary gesture of friendship, she had etched her true Aboriginal name into the figurine with a hot wire. When she gave it to me, she pressed it deeply into my hand. It was a gift to remind me always of her and the journey we had made together. Not surprisingly, I have never forgotten.

There are many other items, such as a pierre noire, the fabled African black stone, a traditional treatment for venomous snakebites, or shoes woven from lime bark by a Belarusian man. Each item has a story; each item stirs an emotion. But of all these personal treasures, my favourite is a plaster cast of a grey-wolf footprint. I made it while tracking wolves in the Sawtooth Mountains for an ITV documentary. Humble as it is, that plaster cast and its story is the inspiration for this book.

Canis lupus, the grey wolf, is an adaptable creature able to live in a wide variety of habitats, from the barren arctic tundra, through the great boreal forest, the diminishing broadleaved woodlands and prairie grasslands to the forbidding desert. The wolf once ranged across most of the North American continent. While the species has always persisted in Canada, within the United States the grey wolf was effectively eradicated from the country by the westward expansion of the population during the nineteenth century and the years which followed. Manifest Destiny for the fledgling America nation spelled Merciless Doom for the American grey wolf.

Today, though, through the reintroduction efforts of conservationists, grey wolves have established populations in northern Wisconsin, northern Michigan, northern Minnesota, western Montana, the Yellowstone area of Wyoming, Idaho, Washington State and Alaska. And in southwest New Mexico and eastern Arizona, a Mexican subspecies of the grey wolf was reintroduced to protected parkland. Successful reintroductions, however, as I would find out, are not always welcomed.

My wolf track is from the Sawtooth Mountains of central Idaho. In 1995, fifteen grey wolves were released, followed the next year by another twenty. While no one knew at the time whether or not the reintroduction would prove successful, the painstaking work of the biologists paid off. When I cast my track in 2009, the population stood at more than 800 wolves. In fact, so well had the population recovered that in just a few days the wolf was to lose its protected status in Idaho and licensed wolf hunting would be permitted.

It was an interesting time to be in Idaho. Tensions were high: on one side stood the federally backed conservationists; on the other a powerful local lobby of hunters and ranchers who were complaining that the wolves threatened their livelihoods and way of life. Both sides had valid arguments, which they expounded with heartfelt passion, while in between, as is so often the case, the wolves stood in the dock, under sentence of death, oblivious to the human debate, simply living according to their nature. Here was an experiment at the frontier of rewilding, teetering on a knife edge.

What I found most alarming, though, was the widespread, profound hatred towards the wolf which I encountered a hatred fuelled and fanned by the malicious lies and anti-wolf propaganda touted by extremists, heating emotions to boiling point, while making no sensible contribution to the debate. So frenzied was the atmosphere that there was a belief that wolves were everywhere and that the community was under siege. It was a bizarre and ridiculous situation.

From a filming perspective, even with the assistance of top local wolf biologists and two of the most experienced American wildlife cinematographers, finding wolves to film proved to be incredibly difficult. A long time had to be spent glassing the terrain in the hope of spotting wolves or, more likely, the ravens that so often follow a pack. Even when we found wolves, they had the edge in the steep mountainous terrain, easily loping up slopes in minutes that would take us as many hours to climb. When I eventually did rest the lens of my scope on a wolf pack, contrary to the propaganda, they were hunting voles not elk.

I was driving one morning when the vaguest movement caught my eye from across a damp meadow. I pulled into a large layby and set up my spotting scope on my tripod. There in the distance were four wolves hunting voles. It was a bad time for the voles: spring melt-waters had evicted many of their number from the security of their burrows, and the wolves were happily cleaning up on the abundance. Off to one side, a large female was sat very forlornly licking a clearly painfully injured foot. Even from my far vantage point, the blood of the wound could be seen. In the background, a large male was more difficult to keep track of.

I estimate that I had been watching the wolves for no more than two minutes when a white station wagon pulled into the layby and parked beside me. Given that the parking area could easily have accommodated two articulated lorries, I realised that my activity was the cause of interest, which was confirmed when a woman stepped out of the drivers door, leaving it open. She was wearing glasses and walked over to me while peering in the direction my scope was pointing. Are those wolves? she asked. When I confirmed her suspicion, she let fly her total venom at such terrible animals. I listened patiently to her rant. She was obviously aware that I was with the film crew word spreads like wildfire in small mountain communities. When she had finished, I asked her if she would like a better look and showed her how to focus and adjust the scope.

Next page

Footprint of an alpha-male grey wolf, cast in dental stone on 1 May 2009 in the Sawtooth Mountains, Idaho, three days before their controversial delisting as an endangered species.

Footprint of an alpha-male grey wolf, cast in dental stone on 1 May 2009 in the Sawtooth Mountains, Idaho, three days before their controversial delisting as an endangered species.