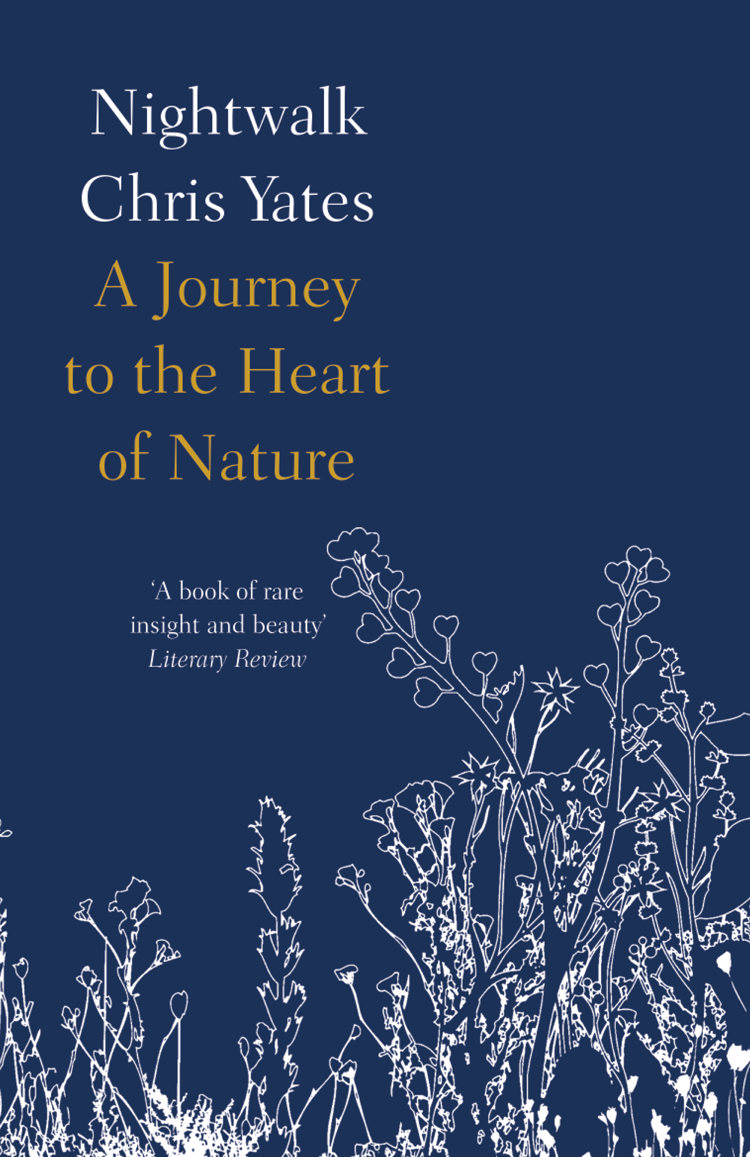

W HEN T IME S LOWS D OWN

Time is short in midwinter, ticking along at the same pace as a man hurrying towards a railway station, but in midsummer time is long and if the man could adjust his pace accordingly he would always miss his train.

From mid June to mid July I hardly ever think about catching trains or buses or anything else that runs to the tick of the clock, but I do think about catching fish because the season on my favourite waters begins at this time and therefore, being a devout angler, I cannot help slowing to the pulse of midsummer as I re-enter a world of quiet ponds, reflected evenings and misted dawns. Since I fledged and learnt to cast a line, half a century ago, I have never failed to return, like a migratory bird, to my summer angling, yet even I appreciate that when the days extend there is time to do more than just fish. Despite my seasonal obsession, I know an evening will come, sometime around the solstice, when all thoughts of fish simply swim away and I shall be drawn instead towards another equally compelling idea.

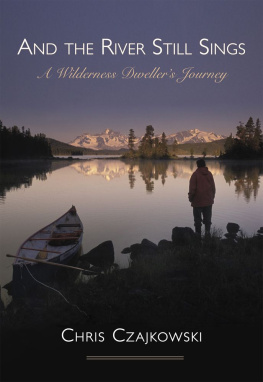

As I write this my rods and tackle are strewn untidily around the room. I am sitting by a window, keeping half an eye on the twin oak trees that stand high up on a slope opposite my house. At the moment their foliage is smouldering gold in the light of the setting sun; soon it will revert to a uniform green before fading through all the blues to grey. Finally, in about an hour, both trees will stand black and formless against the twilight, like cartoon impressions of themselves, and only then, when the whole landscape is in silhouette, will I set out not to fish, but to walk across the narrow midsummer night until the sun reappears in the morning.

Unlike my stillwater angling, which always begins on the sixteenth of June, the nocturnal stroll is a more random event, though its timing does not depend on how good or bad the fishing has been. As I said, it usually happens near the solstice, when the night at this latitude is just a four-hour band of shadow, but if the conditions are unsuitable I will wait until the weather is benign, the air calm and the moon reasonable. For over a month now the airstream has been northerly and the skies clear. The days have been hot, but without atmosphere; the nights have been cold and when the moon was last full it cast a brittle, almost wintry, light. It might seem churlish to be sniffy about cool, clear nights when summer weather is often overcast and soggy, but cold, dry conditions can make the after-dark landscape seem as hollow as an empty shell while mild, soft conditions bring it rustling to life.

Today at about teatime, just as I was thinking of heading back to a lovely willow-cloistered pool, I noticed the distant view from my window suddenly seemed more distant. Opening the window wider, I looked up at a single vaguely fish-shaped cloud that was drifting from the south. The air had more density than before; it smelt of grass and elderblossom and the birdsong it carried had more resonance. Any experienced angler will tell you that a mellowing change of weather like this invariably has a sparkling effect on the fish.

This evening, the ponds and lakes will be jumping, but I will be elsewhere.

L AST L IGHT

The two trees seem to stand more dominantly on the hill now that the sun has just set. A gang of young rooks almost landed in them a moment ago, spinning round the topmost branches and shouting frantically. Perhaps they had spotted a waking owl or maybe they were thinking of starting a new republic, but after a few overhead sweeps they realized it was getting late and beaked off home to their rookery. It is not really late, though. The clock may be saying almost nine thirty, but with the light sinking so slowly there will be plenty of time to savour this pot of tea and still begin my walk before dark.

I prefer to set off on a night stroll at dusk. Not only can the eyes adjust more effectively than if I stepped directly into full darkness from a lit room, I like the way my familiar surroundings are differently transformed by the twilight as I walk through them. Some things melt into their background, others remain solidly fixed yet reveal surprising new identities. Also, there is sometimes an interesting meeting between diurnal and nocturnal nature, like when early bats and late swallows swoop together or a hare is startled by a badger.

Through my open window the sounds of the evening chorus are diminishing and fragmenting, though the song thrush is chivvying what remains of the choir to Keep up! Keep up! Keep up! I can see him sitting in the top of the yew tree in the corner of my garden, chest puffed out, head back, oblivious now to the other songsters, consumed only with his need to proclaim himself. Since he struck up his first tune at five oclock this morning he has hardly given himself time to breathe, let alone feed or attend to any domestic chores. No other songbird can match his endurance. Somewhere nearby his mate is sitting on the nest with her second brood. Is she impressed by his epic daily performance? Is she not a little sick of all the endless repetitions of signature phrases? Surely the message has got through by now. Would she not prefer him to offer more help with the children? Occasionally he smashes a snail and brings it to them, but they are not as important as his song.

He is defiant, like a bugle, while a blackbird is seductive, like a flute, and there is one a real maestro calling from the apple tree in the other corner of the garden. If the thrush wakes me before sunrise, as he has often done since April, I can sometimes get irritated (I am never in bed till well after midnight), but if this particular blackbird rouses me so early I just smile into my pillow. His tone is unmistakably blackbird, but the improvisations, the liquid looping phrases and the unexpected key changes are his alone. He makes a thrush sound mechanical and a nightingale seem monotonous. (There are no nightingales round here any more, but even if there were, late June is always too late for their song.)

Though the owls tawny owls often call in the half-light, they usually allow a short interval after the last songbird before they announce themselves. Depending on their mood and the conditions, they are sometimes mute all night, particularly at this time of year when they have owlets to feed. On other nights, during other seasons, every wood and valley for miles around will be softly echoing to their melancholy voices.

I came to this area with my young family twenty-five years ago, attracted by the rolling chalk downland as much as the streams and rivers that flowed through it. My childhood home was on the North Downs, a hundred miles east, so the topography here seemed familiar despite the hills being higher and the woods more extensive than the ones I used to amble amongst. It is my favourite kind of walking country, and this house, an eighteenth-century estate-workers cottage, is set right in the heart of it. I can step straight out of my door, climb the tree-hung slope behind the house, and set off along paths and tracks that continue uninterrupted for miles. The only people I am likely to meet in the daytime are occasional fellow walkers, shepherds (on quad bikes) and gamekeepers (in Land Rovers). At night, because I go quietly and never carry a torch, I only ever meet the true natives.