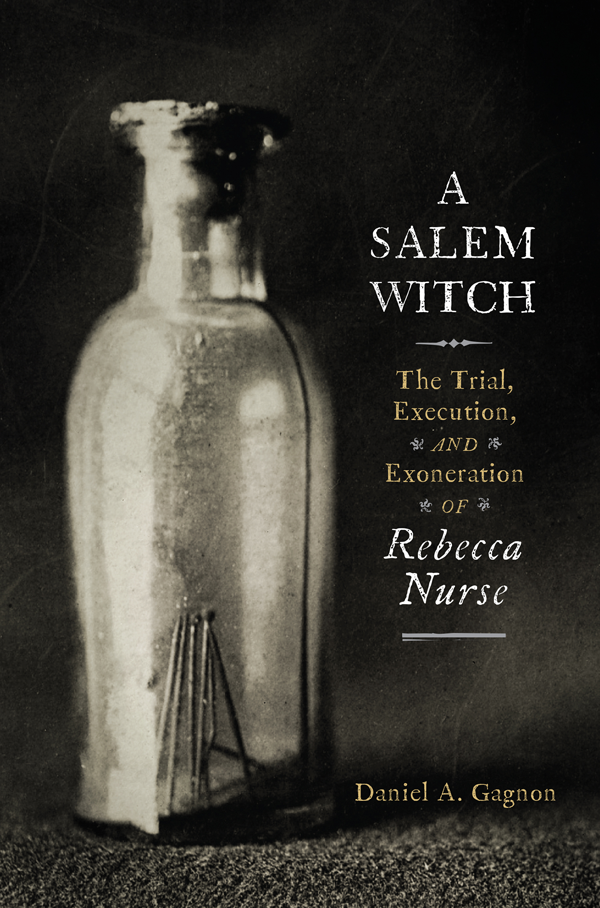

2021 Daniel A. Gagnon

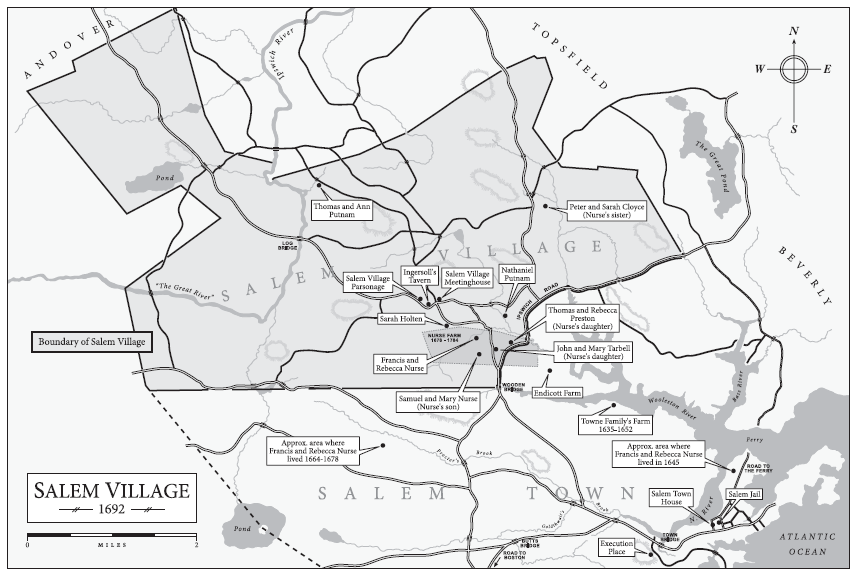

Map by Tracy Dungan. 2021 Westholme Publishing

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

Is breathing freer for thy sake to-day.

Preface

LIKE MANY WRITERS investigating the 1692 Salem Village witch hunt, I was inspired by the actions of those innocents who died in the name of truth, and also by the sense of place associated with Salem Village. For many writers, it is a visit to Salem and the former Salem Village that first leads them to further examine the events of 1692 and the tragic history of those who were wrongfully killed. I am fortunate in that it was not a brief visit, but instead a lifetime thus far spent in the former Salem Village (present-day Danvers, Massachusetts) among the sites associated with 1692 that led me to undertake this project.

Among the seventeenth-century homes, stone foundations, and monuments associated with this dark episode of history, no victim of the witch hunt is remembered to the same extent as Rebecca Nurse. Her story is so compelling that it has been captured in dramatic productions, novels, history books, paintings, films, songs, the name of a rock band, and an academic team at the local middle school, to name only a few ways. Every American high school student who reads The Crucible is familiar with the broad strokes of her part in history.

Yet, previously there was no full-length scholarly biography of Rebecca Nurse. Prior to this project, the only monograph on Nurses life was Charles S. Tapleys slim work Rebecca Nurse: Saint but Witch Victim (1930). A descendant of Nurse and a Danvers historian, Tapley drew primarily on the nineteenth-century secondary sources to construct a brief overview of Nurses role in the trials, without either a full examination of her life before the witch hunt, or a discussion of her legacy after 1692a legacy that has increased in significance since 1930.

This present volume seeks to remedy that gap in the historical scholarship of the 1692 Salem Village witch hunt. Nurse is probably the most well-known victim of the witch hunt today, because she maintained her innocence even though it cost her life, and she is the victim of 1692 who was most extensively memorialized throughout the subsequent centuries.

The Salem Village witch hunt is an event that is hard to comprehend in totality, with hundreds of people involved across a wide area, centered on Salem Village. The stories of individual people can be lost in larger historical examinations of events as complex as the witch huntwhich focus on an abstract discussion of ideology, imperialist conflicts, local politics, and religion. These discussions are important for our understanding of how such an event could occur, but the human element is often lost.

Examining the witch hunt through the life of one of its most well-known victims gives a more manageable perspective and clearer insight into what happened during the events of 1692 as a whole and brings forward the story of one of the most notable women in pre-Revolutionary American history, including how she was commemorated in the following centuries. This focus brings the narrative back to one of human tragedy, and it is easier to see this essential aspect of the witch hunt by focusing on the case of one woman, and how her life and the lives of her family members were affected by this event. Additionally, the chronology of a biography allows the reader to experience the witch hunt as it happened, unlike some historical works on the witch hunt that are arranged thematically or arranged based on the order the accused were put on trial, which distort the chain of events.

As to the text, all dialogue from Rebecca Nurse and statements from those involved in the witch hunt come directly from court records or accounts written by observers of the events and are the original words, as recorded at the time. The language of quotations from original seventeenth-century documents is modernized for clarity and ease of reading. The (seemingly) strange spellings and grammar used in 1692, before the English language was standardized, can subconsciously distance the reader from the main actors of the witch hunt, separating the events from the present day and placing them in another imagined world. In reality, many themes of 1692 connect through the centuries to the present. Also, seeing spelling and grammar that to twenty-first-century readers appears incorrect, the reader may mistakenly draw conclusions about the education and intelligence of the writer or speaker. Modernizing the language is meant to help the reader avoid these twenty-first-century presuppositions.

Along with the language, the dating system is also slightly modified for the modern reader. The Julian calendar (with the year beginning on March 25, and dates eleven days behind the current Gregorian calendar) was still used in seventeenth-century New England, or sometimes the two calendars were merged and dates between January and March of a certain year were listed as both years (for example, the beginning of the witch hunt took place in 1691/2). Years in this text are noted as starting on the more familiar January 1.

Finally, in order to give a full account of the life of a seventeenth-century Puritan woman, much is also said about her husband, Francis Nurse, and other members of her family. As Massachusetts women at that time could not own property in their own name, and legal acts (such as wills, adoptions, etc.) were in their husbands name, Francis name shows up exponentially more in the pre-1692 records than Rebeccas. This disadvantage is due to the society in which Rebecca Nurse lived, and the historical record suffers because of it. However, although her name is not on a deed or she is not listed as the legal guardian of an adopted child, one should not assume that she was not working alongside her husband on the farm or that she was not intimately involved in raising the child. These records that mention Francis Nurse reveal much about Rebeccas life.

Rebecca Nurses story resonates for us today, as it has for those in previous centuries, and surely will for subsequent ones. It fills us with a desire for justice, and a respect for those who stand firm in the shadow of persecution. In the words of one local visitor to the Rebecca Nurse Memorial in 1900, Perhaps the greatest incentive to ideal living in a changing world is the firmly held conviction that truth will finally vindicate itself. When this vindication becomes apparent, as in the case of one of the most striking martyrs of the Salem witchcraft, Rebecca Nurse, progress seems assured. Let us work toward that vindication and use the past as a way to look to the future.