Acknowledgments

T his book took a long time to write and, given its historical and geographic reach, depended on the expertise of both friends and strangers. An invitation by Linda Gregerson to give a talk at the Early Modern Seminar at the University of Michigan in 1997 gave rise to my initial thoughts on the relation between the institution of slavery and the culture of taste. I would like to thank Linda for inviting me to think of difference outside my period, and Valerie Traub, who wanted me to go even further back in time. My former colleagues at the University of Michigan created the interdisciplinary conditions in which this project was conceived. The late Lemuel Johnson was perhaps my most important interlocutor, and his resistance to my ideas often led me in productive directions. Larry Goldstein published an early version of what became in the Michigan Quarterly Review, and I thank him for his enthusiastic support. Ifeoma Nwankwo invited me back to Michigan to continue conversations about slavery and the making of modern culture with members of the Atlantic Studies Program and was instrumental in a later invitation to Vanderbilt University. I would like to take this opportunity to thank her for her collegiality and friendship.

Early fragments of the book were presented as lectures or seminar papers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, at the invitation of Susan Stanford Friedman and Neil Whitehead, and at the University of London, where my friend Mpalive Msiska provided me with a forum for enlightened conversations. The middle (American) sections of the book were written during my membership in a working group on slavery and representation at Yale University's Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. I am grateful to Deborah McDowell, John Stauffer, and David Blight for convening the working group. At the Yale workshop and later at Rutgers, Mia Bay provided me with important guidance in the area of historical investigation.

Versions of the last part of the book benefited from the intervention of individuals and groups at several institutions where I was invited to share my research. Members of the postcolonial working group at Royal Holloway College nudged me to think about the meaning of slavery in the culture of the present, and I would like to thank Helen Gilbert and Elleke Boehmer for their hospitality and David Lambert for directing me to new work in the geography of the Atlantic world. At the University of Rostock, at a conference convened under the auspices of the Institute for English and American Studies, Gesa Makenthun and Raphael Hormann provided me with an opportunity to rethink the relation between the aesthetic and forms of bonded labor. Jay Clayton invited me to Vanderbilt University, where conversations with Ifeoma Nwankwo, Colin Dayan, Houston Baker, and Hortense Spillers pushed me in new directions. At the University of Minnesota, I had the privilege to present a version of the last chapter of the moment thanks to the efforts of Jani Scandura and her colleagues.

The careful, sustained, and substantive reading of three tough anonymous readers immensely enriched this book. While I may have disagreed with some of their responses, I benefited from all of their criticism and thank them profusely for the energies they put into the book. At Princeton University, my chairs, Michael Wood and Claudia Johnson, created the ideal conditions for writing this kind of book, and their generosity and support enabled me to complete the work in a time of change and transition.

At Princeton University Press, Hanne Winasky, with the able assistance of Adithi Kasturirangan and Christopher Chung, nurtured the book through what appeared to be a long process, and I thank her for her professionalism and friendship. Kathleen Cioffi guided the book through the production process with professionalism and care. Many thanks to Jill R. Hughes for copyediting the manuscript meticulously and for respecting my style. Sonya Posmentier was an invaluable research assistant. Valerie Smith and Abiola Irele provided me with unconditional friendship and intellectual mentorship, and my debts to both are immeasurable. My family lived with this book for so long that they cannot imagine a time when it didn't exist. Juandamarie Gikandi provided me with the comforts of home that made it all possible. I thank my children, Samani, Ajami, and Halima Gikandi, for bearing life under the shadow of the book, and I dedicate this work to them with love and devotion.

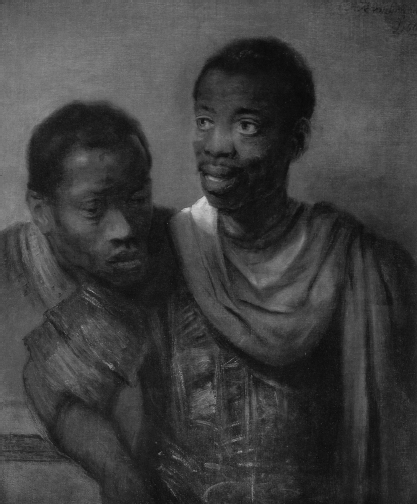

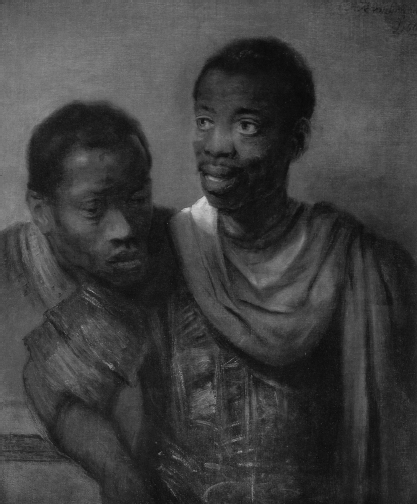

1.1 Harmenszoon van Rijn Rembrandt, Two Negroes. 1661.

Overture:

Sensibility in the Age of Slavery

S ometime around 1659, the Dutch painter Harmenszoon van Rijn Rembrandt sat in his studio in Amsterdam and commenced work on Two Negroes (

In the same year that Rembrandt was ennobling the black in the aesthetic sphere, affirming the humanity of the African in unmistakable and unequivocal terms, the Dutch merchant Pedro Diez Troxxilla wrote a receipt for the slaves he had received from Matthias Beck, governor of Curaao:

I, underwritten, hereby acknowledge to have received from the Hon'ble Matthias Beck, governor over the Curaao Islands, sixty two slaves, old and young, in fulfillment and performance of the contract concluded on the 26th June, A'o 1659, by Messrs. Hector Pieters and Guillaume Momma, with the Lords Directors at the Chamber at Amsterdam; and as the negroes by the ship Coninck Salomon were disposed of, long before the arrival of the undersigned, and the ship Eyckenboom, mentioned in the aforesaid contract, has not arrived at this date, the said governor has accommodated me, the undersigned, to the best of his ability with the abovementioned sixty two slaves, and on account of the old and young which are among the aforesaid negroes, has allowed a deduction of two negroes, so that there remain sixty head in the clear, for which I, the undersigned, have here according to contract paid to the governor aforesaid for forty six head, at one hundred and twenty pieces of eight, amounting to five thousand five hundred and twenty pieces of eight. Wherefore, fourteen negroes remain still to be paid for, according to contract in Holland by Messrs. Hector Pieters and Guillaume Momma in Amsterdam, to Messrs. the directors aforesaid, on presentation of this my receipt, to which end three of the same tenor are executed and signed in the presence of two undersigned trustworthy witnesses, whereof the one being satisfied the others are to be void. Curaao in Fort Amsterdam, the 11th January, A'o 166o. It being understood that the above fourteen negroes, to be paid for in Amsterdam, shall not be charged higher than according to contract at two hundred and eighty guilders each, amounting together to three thousand nine hundred and twenty Carolus guilders.

The receipt was more than the customary acknowledgment of goods received; it was also a detailed inventory of objects of trade and the geography in which they were exchanged. And this correspondence, dated June 1659, can be read as a sample of the functional idiom of what would come to be known, in the verbal trickery of euphemism and understatement, as The African Trade, a triangular commerce joining the industrial centers of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. What made this trade unique in the history of the modern world was that its primary commodity was black bodies, sold and bought to provide free labor to the plantation complexes of the new world, whose primary productscoffee, sugar, tobaccowere needed to satiate the culture of taste and the civilizing process. In this triangle, African bodies mediated the complex relations between slave traders like Troxxilla, colonial governors such as Beck, and the unnamed but powerful directors of the Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce.

Next page