Judith Herrin - The Formation of Christendom

Here you can read online Judith Herrin - The Formation of Christendom full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

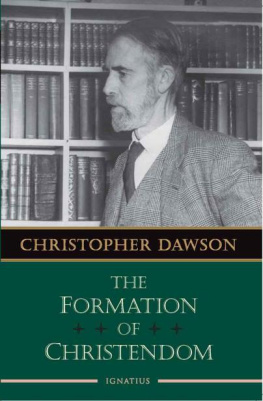

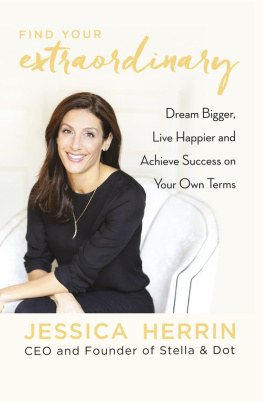

- Book:The Formation of Christendom

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Formation of Christendom: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Formation of Christendom" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Formation of Christendom — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Formation of Christendom" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE FORMATION OF CHRISTENDOM

The Formation of Christendom

JUDITH HERRIN

With a new preface by the author

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 1987, by Princeton University Press

Preface to the Princeton Classics edition copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey, 08504

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021939835

First Princeton Classics Paperback edition, 2021

Paperback ISBN 9780691219219

eISBN 9780691219219 (ebook)

Version 1.0

Cover photo (top): by Kieran Dodds, (bottom): iStock

Cover design by Michael Boland

For Anthony

- viii

- ix

- xvii

- 3

- 15

- 19

- 54

- 90

- 129

- 133

- 145

- 183

- 220

- 250

- 291

- 295

- 307

- 344

- 390

- 445

- 477

- 481

- 489

- 493

- LIST OF FIGURES

- . Map of the World of Late Antiquity16

- . Map of the Mediterranean East130

- . Map of the Christian West293

- . Comparative Chronology532

(In a separate section, following )

.Bridge of Fabricius, Rome, third century. (Photo: Courtauld Institute, London.)

.Land walls of Constantinople, fifth century. (Photo: Courtauld Institute, London, by G. House.)

.St. Sophia, Constantinople, sixth century. (Photo: Byzantine Visual Resources, 1968 by Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.)

.Icon of Christ and St. Menas from Bawit. (Photo: Clich des Muses Nationaux, Paris.)

.Icon of Madonna and Child, Pantheon, Rome. (Photo: Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione, Rome.)

.Gospel book cover, treasury of the Church of St. John the Baptist, Monza. (Photo: Courtauld Institute, London.)

.Votive crown of King Recceswinth, Museo Arqueologico Nacional, Madrid. (Photo: Instituto Amatller de Arte Hispanico, Ampliaciones y Reproducciones MAS.)

.The Monastery of St. Catherine, Mount Sinai. (Photo: Courtauld Institute, London, by R. Cormack.)

.Byzantine and Islamic coins. (Photos A, C, and F: The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham; reproduced with the kind permission of the Trustees. Photos B, D, and E: The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.)

.The Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem. (Photo: Courtauld Institute, London.)

.The Great Mosque of Damascus. (Photo: Courtauld Institute, London.)

.Medieval Greek and Latin minuscule scripts. (Photos: The Bodleian Library, Oxford; Berlin (West), Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz.)

.Mosaic of St. Peter, Pope Leo III, and Charlemagne; Rome. (Photo: Windsor Castle, Royal Library, 1988 by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.)

.Manuscript of the Rule of St. Benedict, Latin with Old High German translation. (Photo: Monastery of St. Gall, Switzerland.)

.Manuscript of the Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. (Photo: Warburg Institute, London.)

.The Chludov Psalter, Moscow State Historical Museum. (Photo: Courtauld Institute, London, by D. Wright.)

IT IS A strange honor for an author to be invited, after more than thirty years, to republish a book that is now deemed a classic. I must therefore begin by alerting any new reader to two features of The Formation of Christendom. First, this is the work of a young woman, written with youthful overconfidence and determination. Second, since it was published in 1987, an enormous amount of high-quality research has been undertaken on the period it covers, circa A.D. 500-800. Our knowledge of the period has been transformed, which means it would be an impossible task to try and update the book. In addition, I feel that its spirit and energy should be retained.

This book sets out to show how the entire Mediterranean world between the sixth and ninth centuries A.D. was shaped by a set of forces thatalthough they formed different societiesvenerated the same single God, divided over his nature, contested how to worship him, and struggled to attain a heavenly afterlife. From the periphery of this world, non-Roman agents remade a Roman Empire that was centered in its enormous, new capital of Constantinople. The shared origins of the West, the East, and the Islamica tripartite division that still haunts usgo back to this early formative period when each was in active relationship with the others. Such is the claim of The Formation of Christendom.

By way of introduction, Ill try to answer three questions: How did I come to write a history with this ambition? What sort of a historian does it make me? What would I change, were I to update it?

When I studied European history as a student at Cambridge in the early 1960s, I felt constrained by the blinkered focus on the British Isles, France, and Germany. I became aware of Byzantium thanks to lectures by Philip Grierson, who used the evidence of coinage to point out the existence of a long-lasting empire that was not part of the West yet exercised considerable influence over it. It had a spectacular gold currency, the solidus, that remained stable for over seven hundred years, suggesting there was far more to the history of Europe than was generally taught. This provoked in me an interest in Byzantium from a comparative point of view and led me to do a PhD at Birmingham University under the guidance of Anthony Bryer. I decided to contrast an area under Byzantine imperial rulecentral Greece in the twelfth century, documented in the letters of ecclesiastics like Michael Choniates, Metropolitan of Athenswith a more familiar region of the West, selecting the northern European homeland of Geoffroi de Villehardouin and Guillaume de Champlitte, knights who participated in the Fourth Crusade, which captured Constantinople in 1204. I hoped to trace differentiating elements in these two styles of government, imperial and Western, in the complex thirteenth-century social formation that resulted from the crusaders conquest of central Greece and the Peloponnese. It proved impossible to complete this overambitious comparison, but studying Choniatess letters provided me with a familiarity with Byzantium from within and strengthened my resolve to make this medieval empire more familiar.

The contrast between Byzantine and Western medieval art led me to the importance of icons and then to the paradox of iconoclasm, which was the topic of the Birmingham Spring Symposium in 1975. With Bryer, I edited the papers in what was the first publication of the Centre for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. Since fairly stylized images of Christ, the Apostles, the Virgin Mary (known as Theotokos, Mother of God), and saints were greatly revered in Byzantium, how could they have provoked the battle of icons, which involved removing and destroying these holy images? It was through my study of iconoclasm that I realised more fully what a critical role the Arabs played in Byzantine history. From the revelations of the Prophet Muhammad in the early seventh century onward, which I now know were not written in classical Arabic but in a dialect of Mecca used in much earlier oral poetry, Islam challenged Byzantium in multiple waysnot merely military. In order to survive as a Christian medieval empire, the eighth-century emperors had to put the entire society on a war footing and concentrate all efforts to resist Muslim expansion. Leo III and his son Constantine V are famous for introducing iconoclasm, yet closer investigation of their policies revealed the inner strengths that guaranteed survival and the growth of Byzantium into its medieval state character.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Formation of Christendom»

Look at similar books to The Formation of Christendom. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Formation of Christendom and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.