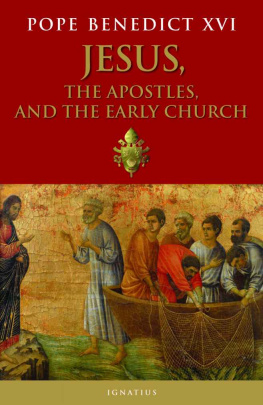

A STUDY GUIDE

FOR

JOSEPH RATZINGERS

(POPE BENEDICT XVI)

JESUS

OF NAZARETH

PART TWO: HOLY WEEK FROM THE ENTRANCE

INTO JERUSALEM TO THE RESURRECTION

Foreword by

Timothy Gray, Ph.D.

Introduction by

Mark Brumley

Outlines and Questions by

Mark Brumley, Curtis Mitch, and Laura Dittus

Summaries and Glossary Terms by

Mark Brumley and Curtis Mitch

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations (except those within citations) have been taken from the Revised Standard Version of the Holy Bible, Second Catholic Edition, 2006. The Revised Standard Version of the Holy Bible: the Old Testament, 1952, 2006; the Apocrypha, 1957, 2006; the New Testament, 1946, 2006; the Catholic Edition of the Old Testament, incorporating the Apocrypha, 1966; 2006, the Catholic Edition of the New Testament, 1965, 2006 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

All rights reserved.

Front cover art (left):

Christs Passion: Descent from the Cross

Front cover art (right):

Christs Appearance Behind Locked Doors

The Maest Altarpiece

by Duccio di Buoninsegna

Museo dellOpera Metropolitana, Siena, Italy

Scala / Art Resource, New York

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

2011 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-605-1

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Foreword

The Second Vatican councils Dogmatic constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum (The Word of God), outlined the essence of a catholic approach to Scripture as combining both history and theology. On the one hand, the council emphasized the importance of studying the historical context of Scripture for understanding the meaning intended by the human author of a particular text of Scripture. This means literary genre, social context, and understanding of ancient languages and cultures must all be taken into account to best understand the text of Scripture within its historical context. On the other hand, since the human authors were inspired by the Holy Spirit, one must also be sensitive to the divine Authorship at work in Scripture. Thus, although the Bible is made up of seventy-three different books, by numerous authors (sixty-six books in the Protestant Bible), over a long period of time, it must still be understood within the context and unity of Gods plan. This approach, now often referred to as canonical exegesis, will be important for Pope Benedicts approach to Scripture, since it contains a record of Jesus words and deeds. This theological dimension of Scripture must also be read within the living Tradition of the Church and according to the analogy of faith. In other words, Scripture is to be read within the Church, a vital point that Pope Benedict has repeatedly made.

History and Theology

Indeed, both of these methodological approaches, the historical and the theological, are seen as essential in Pope Benedict XVIs post-synodal apostolic exhortation on Scripture, Verbum Domini (The Word of the Lord). In a sense, history and theology are the two ears by which we must hear, in stereo, the word of God. For Vatican II and Pope Benedict, history and theology are the two legs upon which a proper exegesis must standneither leg can stand alone. Thus, Benedict observes in Verbum Domini that only where both methodological levels, the historical-critical and the theological, are respected, can one speak of a theological exegesis, an exegesis worthy of this book ( Verbum Domini 34; hereafter abbreviated VD ). Just as faith and reason are the two wings by which we ascend to God (according to Pope John Paul IIs encyclical on faith and reason, Fides et Ratio ), so too, history (reason) and theology (faith) are the two wings by which we are to ascend to an understanding of Gods word.

It is worth noting that volume two of Jesus of Nazareth is the first major work of Benedict after his outline of the key principles of catholic biblical interpretation given in Verbum Domini . One of the striking features of Jesus of Nazareth, Part Two is his modeling, rather consciously, of how a catholic scholar should read Scripture. Indeed, in his preface, he notes that the historical-critical hermeneutic (approach to reading Scripture) should be combined with the theological approach, which is the art of reading the Bible that needs to be recovered. He goes on to say that fundamentally this is a matter of finally putting into practice the methodological principles formulated for exegesis by the Second Vatican council (in Dei Verbum 12), a task that unfortunately has scarcely been attempted thus far ( Jesus of Nazareth, Part Two , p. xv, emphasis added). Note the rather strong words, finally and scarcely. Attending to both the historical and theological dimensions of Scripture together is something that, in the Popes mind, is rarely being done. This, in short, is the methodological aim of his book on Jesus; for in addition to his desire to search the face of God in Jesus and thus bring a deeper reflection upon the figure of Jesus, his other aim is to model this rare art of combining history and theology, in his study of the Word made flesh.

Thus, my aim in this foreword is to walk through the principles of catholic interpretation that the Pope outlines in Verbum Domini , and show how he practices what he preaches in his second volume of Jesus of Nazareth .

History

In Verbum Domini , Pope Benedict mentions that although the historical and theological approaches, or hermeneutics, are distinct, they should not be separated or opposed. He warns of a sterile separation that is often present in historical methodology, when it is cut off from theology ( VD 35)such isolation of historical and rational methods of study from theology and faith stems from a positivistic and secularized hermeneutic ultimately based on the conviction that the Divine does not intervene in human history ( VD 35). This narrow methodological approach, which often handicaps historical critics, is precisely the flawed method that the Pope critiques in his preface to volume two of Jesus of Nazareth , where he singles out the positivistic hermeneutic, which itself is a specific and historically conditioned form of rationality that is both open to correction and completion and in need of it ( Jesus of Nazareth, Part Two , pp. iv-xv). The problem is not history, but rather the philosophical presuppositions that too often undergird how historical methods are employed and viewed. In other words, an exegete who reads Scripture using historical methods with the philosophical notions that there is no God who exists or who enters history will likely conclude that the divine and supernatural elements of Scripture are not historical.

In reaction to such errant conclusions some have turned against history and reason and have wanted to read the Bible by faith alone. Such a fundamentalist approach, however, is rightly condemned; it is not wrong in affirming the place of faith, but rather in its throwing out of reason. Unfortunately, those in the academic world who seek to shut out faith all together also often condemn the pursuit of combining reason with faith as a fundamentalism. This rationalism, however, which seeks reason alone, is just as flawed as the fundamentalist who seeks faith alone. Benedicts critique of this approach is seen in his concluding remarks on the meaning of Jesus atoning death, saying that too often exegetes exclude the theological dimension of atonement, and thus he warns that the mystery of atonement is not to be sacrificed on the altar of overweening rationalism ( Jesus of Nazareth, Part Two , p. 240). Thus, in response to the strident secularism that seeks a separation from faith, Benedict argues in Verbum Domini that the true response to a fundamentalist approach is the faith-filled interpretation of sacred Scripture ( VD 44).

Next page