3 by Northern Illinois University Press

Published by the Northern Illinois University Press, DeKalb, Illinois 60115

Manufactured in the United States using acid-free paper.

All Rights Reserved

Design by Yuni Dorr

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Havers, Grant N., 1965

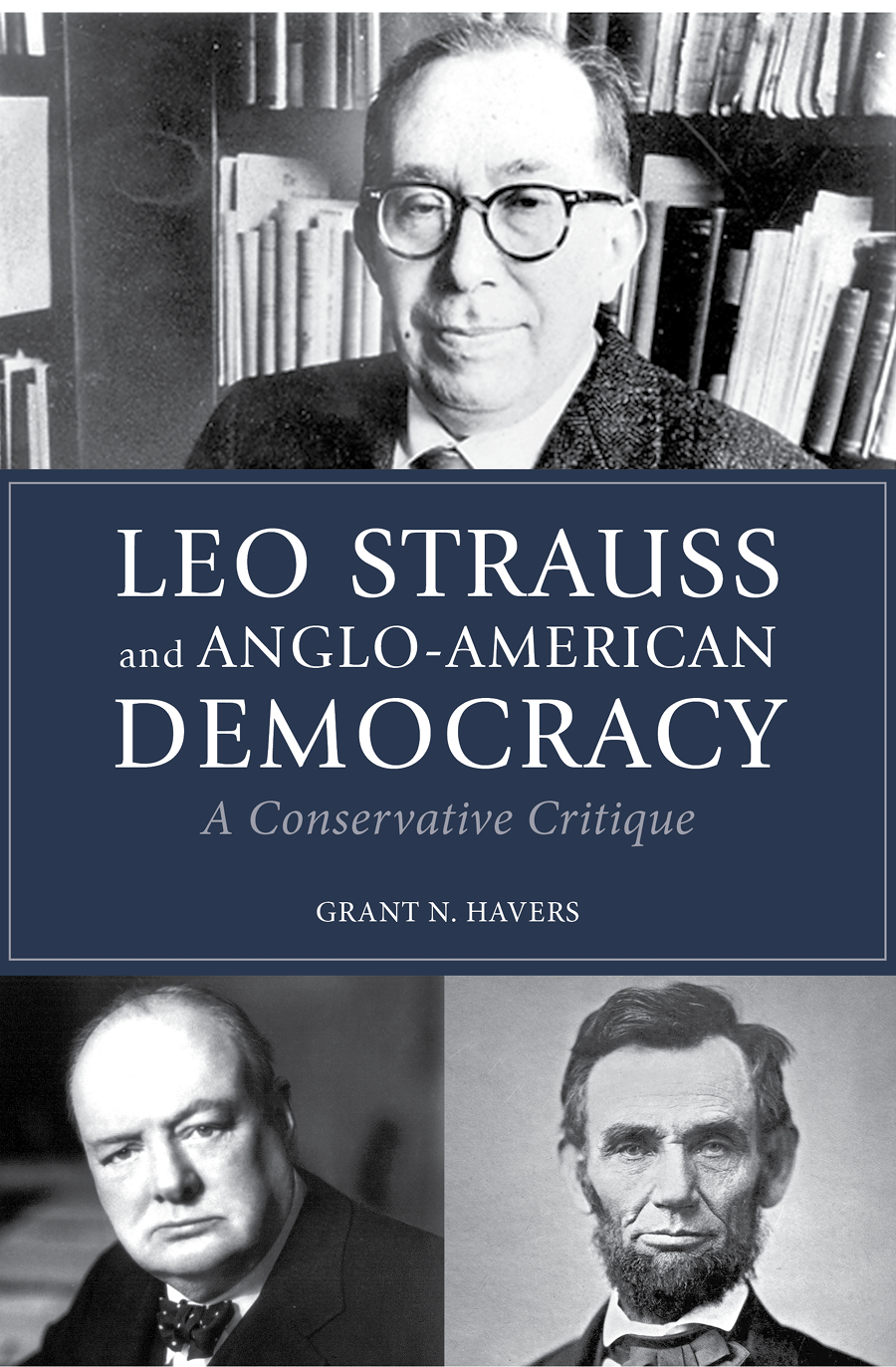

Leo Strauss and Anglo-American democracy : a conservative critique / Grant N. Havers.

pages cm

Summary: Interprets Leo Strausss political philosophy from a conservative standpoint and argues that Strauss was a Cold War liberal. Suggests inattention to Christianity is crucial to the Straussian portrayal of Anglo-American democracy as a universal regime whose eternal ideals of liberty and constitutional government accord with the teachings of Plato and Aristotle, rather than the GospelsProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-87580-478-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-60909-094-4 (e-book)

1. Strauss, Leo. 2. Political sciencePhilosophy. 3. ConservatismPhilosophy. 4. Political scienceUnited StatesHistory. 5. Political scienceGreat BritainHistory. I. Title.

JC251.S8H38 2013

320.52092dc23

2013012135

To My Love,

Therese

Fides quaerens intellectum

Contents

Saving Anglo-Americans from Themselves

Athens in Anglo-America

Leo Strauss, from Left to Right

Churchill, the Anglo-American Greek?

The Anglo-American Struggle with Strauss

Leo Strauss and the Uniqueness of the West

It has been over twenty-five years since I read my first book by Leo Strauss. At the time, I was enrolled in a graduate seminar course in the So cial and Political Thought Program at York University in 1987, which focused on the complex relation between the Bible and philosophy. One of the course texts was Spinozas Theologico-Political Treatise . Brayton Polka, the professor in the course who later supervised my doctoral dissertation on Spinoza, was deeply critical of Strauss. Yet he included Strausss Spinozas Cri tique of Religion in the courses bibliography of secondary sources. Although this work, which first appeared in German in 1930, was my first introduction to Strauss, it was not an introduction to the phenomenon of Straussianism. The only inkling I had of Strausss wider influence up to that point was gleaned from my undergraduate reading of the essays of George Grant, a Canadian conservative philosopher who generally had nothing but praise for Strauss. For most of my graduate study, I read Strauss as a profound interpreter of Spinoza as well as one of the few twentieth-century philosophers who actually took seriously the relation between reason and faith. I was intrigued that a philosopher of Strausss high caliber even wrote on the Bible. As a born and bred Protestant who has never been persuaded that the Thomistic synthesis of Aristotelian philosophy and biblical revelation withstands scrutiny, I was impressed that a man of Strausss intellect repudiated any attempt to suppress the tensions and differences that existed between Athens and Jerusalem. Yet I was unaware at this time that Strauss had inspired a movement in political philosophy that had an impact far beyond the halls of academe. Although a Straussian scholar served on my dissertation committee, I had no idea there was a wider political debate, a veritable Strausskampf , over the true meaning of this philosophers ideas and objectives.

My original apolitical understanding of Strauss that was nurtured in graduate school eventually gave way to a more intense interest in his influ ence on postWorld War II conservatism, an influence that was already deeply reflected in the ideology of neoconservatism. While seeking a full-time teaching position in the 1990s, I was persuaded that Strausss recovery of Greek political philosophy as the only way to address modern relativism and nihilism was reliably conservative. Since my parents raised me to re vere the defenders of traditional English constitutionalism as well as the statesmanship of Lincoln and Churchill, the Straussian praise of these fig ures resonated with me. It did not occur to me at the time that Strausss line of thinking fits best into Cold War liberalism, a relatively new political tradi tion that was anti-conservative in many respects. This new version of liberalism, after all, stressed the importance of spreading liberal democratic ideals around the world, especially in the struggle against a totalitarian regime that had its own far more brutal version of universal credos.

As my own political views shifted sharply to the Right, it gradually dawned on me that Straussianism was a supremely important phenomenon precisely because Strauss and many of his most politically active students had almost succeeded in transforming conservatism, particularly its Anglo- American incarnation, into a doctrine that called for the democratization of the world. What all this had to do with distinguished conservatives such as Edmund Burkewho were deeply skeptical of political abstractions that justified grand projects of social engineeringwas (and still is) beyond my comprehension. By the time that the second Iraq War had begun in 2003, a renewed debate over the meaning of Straussianism and neoconservatism crossed over from academe into the blogosphere, where instant experts on Strauss sprouted like mushrooms. At this time, I was gradually coming round to the view that Straussianism was a formidable adversary of everything that remotely stood for conservatism in the modern age. As a conservative Christian, I was also particularly troubled that Strauss gave short shrift to the influence of Christianity on Western political philosophy. What was doubly frustrating to me and other conservatives around this time was that the mainstream debate over Strauss was largely confined to an argument between leftist opponents of Strauss who saw him as a far rightist and his supporters who defended him as a liberal with some conservative tendencies. Very few critiques from the right-wing side of the spectrum have garnered popular attention. Although I wrote extensively on the Straussian reinvention of the American political tradition in my first book, a study of Abraham Lincolns political theology, it recently occurred to me that Strauss and his students deserved their own book from a perspective that often receives little attention in todays debates. The purpose of this book, then, is to show how Strauss and his students offer a defense of Anglo-American democracy that is conservative in name only.

During this long journey from my study of Strauss to my critique of Straussianism, I have benefited immensely from the knowledge of others who have been longtime participants in the Strausskampf . I am eternally grateful to Paul Gottfried, who urged me to write this manuscript just as he was completing his own book on Strauss, for painstakingly reading and commenting on several drafts of this study. Without the benefit of Pauls unsurpassed knowledge of conservatism, I would not have been able to write this book. When Paul and his co-editor Claes Ryn published an essay of mine on Leo Strauss and Willmoore Kendall in the journal Humanitas in 2005, to which they both wrote critical replies, their kind attention to my work provided an additional catalyst for this book-length study of Strauss. I thank both Paul and Claes for encouraging further intellectual percolations. Peter Minowitz, who knows more than anyone about the intricate details of the controversies surrounding Strausss legacy, also took the time to read the manuscript in rough as well as to offer invaluable suggestions that saved me from making more than a few unsubstantiated claims about Strauss and his students. Calvin Townsend also deserves my profound thanks for engaging in a decade-long dialogue with me about the subtle differences and disputes that have arisen in the Straussian movement since Strausss death in 1973. Conversations with Phillip Wiebe, Christopher Morrissey, and Raymond Tatalovich on topics ranging from medieval scholasticism to American republicanism have encouraged me to reconsider many snap judgments about the relation between philosophy and politics. It was also a great blessing to have two first-rate anonymous peer reviewers who carefully and insightfully offered necessary suggestions for revising the text. Finally, I am very grateful to both Amy Farranto, acquisition editor of Northern Illinois University Press, for overseeing the early stages of the manuscript review, and Susan Bean, managing editor of NIU Press, for diligently helping me hammer out a readable manuscript that is suitable for readers who are not as obsessed with Strauss as I am.

Next page