Existential Rationalism

Marcel Eschauzier

Existential Rationalism

Handling Humes Fork

Copyright 2021 Marcel Eschauzier

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any matter without the written permission of the copyright owner except for the use of quotations in a book review.

ASIN B09MR33PL2 (ebook)

ISBN 979-8775242817 (paperback)

ISBN 979-8774922246 (hardcover)

XRLMedia December 2021

For Ioana

... to think outside that assumption [that people can have knowledge of an objective reality] requires not so much intelligence as a radically free yet prehensile act of intellectual imagination, misunderstanders include individuals of the highest intelligence. The form of imagination required is rarer than intelligence. The most gifted of creative artists have it, including great writers, but I fear not many academics.

Bryan Magee (2016), Ultimate Questions . Princeton University Press.

Bryan Magee (1930-2019) was a British philosopher, BBC broadcaster, politician, and author who brought philosophy to a popular audience.

The desire to transcend conceals the truth.

Contents

The original story of existential rationalism

T he vile grey of a Sunday morning had blossomed into full daylight. High up on my balcony, I could see how the tall buildings still trapped a veil of mist on the lake. The distant howling of a police car. A street dog barking. Almost twenty years ago, I had left the Netherlands. My restlessness and curiosity had propelled me into a nomadic lifestyle searching for existential clarity in the four corners of the world. A consultant job was my vehicle to live in different countries and cultures. Mexico, Hong Kong, South Korea, Romania, Germany, France, Spain, Sweden, Australia: it had been a fascinating ride.

Travelling h elped me discover how preciously little I knew and patch some of my ignorance with real-life experience. My favorite learning method was making mistakes: painful yet effective. Practical experience is an excellent starting point to answer, arguably, the most pertinent existential question: how should I live life? The question raises related metaphysical and psychological issues. Who am I, and why do I experience life as I do? What can people know about the world anyway?

I also looked in other ways for answers, like reading about philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, even physics. Being curious can be exhausting, especially when you have a low tolerance for cognitive dissonance like myself. What control do I have over my existence? What is the nature of my free will? How to live deliberately and suck out all the marrow of life? How to love? How to deal with disappointment? I found life thoroughly confusing. Until that moment on the balcony. The journey finally paid off when I got the clarity I had been looking for. I came home.

This book tells the story of what I found.

As an engineer, I was pleased to learn from Western philosophy because it uses reason to seek answers. Engineers must be rational because the world is unforgiving for those who are not. I was particularly impressed by the philosophical work of David Hume (1711-1776). With inevitable logic, Hume shatters our hope of having certainty about anything that exists in the world. He refutes the rationalist views of Plato and Descartes before him. Still, many illustrious thinkers after Hume could not let go of the dream of conceptual certainty about the world. We will meet some of them in Chapter 9 Tall tales of higher truth . Hume sent rationalism into hibernation. But its time to end its slumber.

It struck me that there is little consensus in Western philosophys answers to lifes great questions. As people, we are creatures of a single species inhabiting the same world. Why didnt we manage to reach more finality in existential answers? I could not help but feel a bit disappointed with what Western philosophy had come up with after more than two and a half thousand years.

I extended my search into what Eastern philosophy had to offer. I must admit that, to this day, I remain a novice in this field. I have a thoroughly Western mindset. Even so, I found the work of Alan Watts (1915-1973) very instructive. He explains the essence of Oriental philosophy with British articulateness so that my Occidental mind could get it.

A pivotal moment was the insight that I got that fateful morning, standing on my balcony. It was a moment of absolute clarity. There was nothing supernatural or mystical about it, yet it was spiritual and life-changing. The Japanese Zen-Buddhist term for this experience of insight is satori. Suddenly I could answer the questions of who I am and why I experience life as I do. I resolved what philosopher David Chalmers (born in 1966) calls the hard problem of consciousness.

A brief word to outline Chalmers position: he subscribes to the academically popular distinction between phenomenal consciousness and so-called access consciousness. The former contains qualia, being the experiences from the immediate perspective of the subject, while the latter holds information that is not immediate and subjective. Access consciousness content is therefore accessible for cognition, communication, and control of behavior. Chalmers considers that we understand the mechanics of access consciousness since they are merely easy problems of consciousness. The phenomenal experience remains unexplained, making it his hard problem of consciousness.

Shortly after this satori-experience, I also realized how to respond to other existential questions. What can we know about the world? How to live life? Like satori, it was an experience of insight, and with this insight came all the answers. Later, when reading about it, I could confirm that I had found something known as Tao.

It became clear that I had been chasing my tail by searching for existential clarity. The answer was, so to say, my tail, and the harder I pressed to find it, the more it eluded me. I had been looking for the answers to my existential questions. What I did not realize was that my search was the answer.

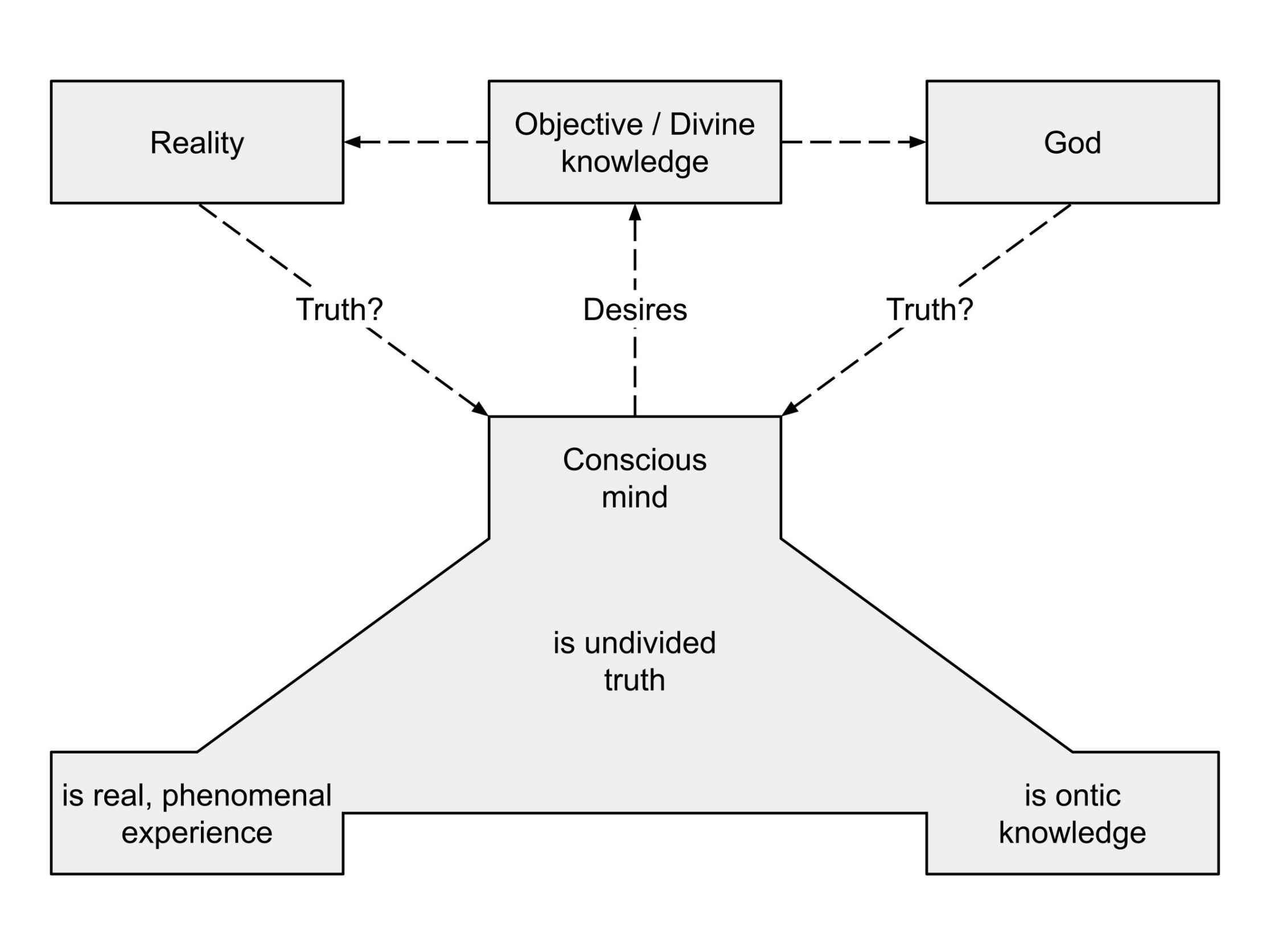

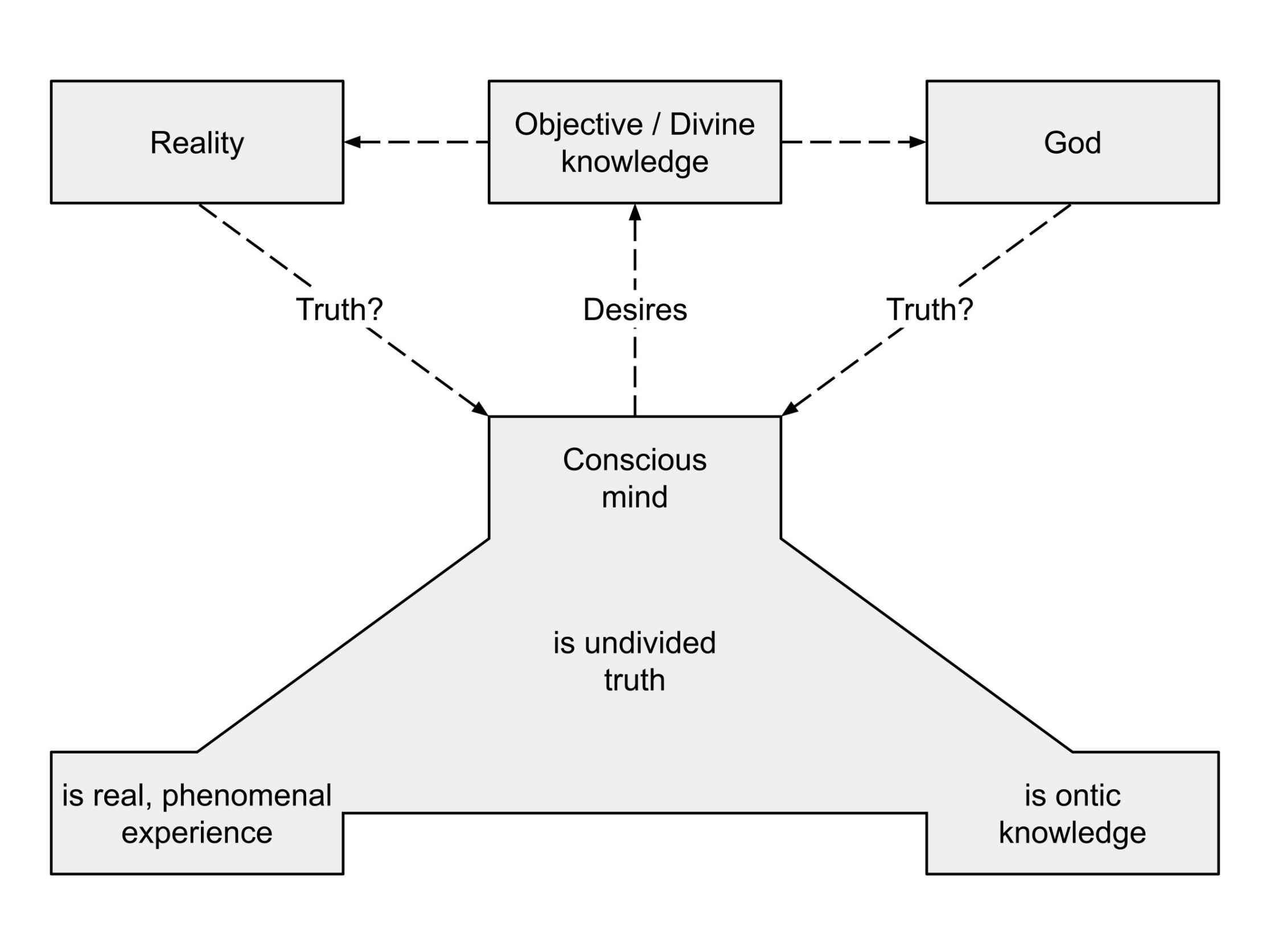

The epistemological (meaning knowledge-theory related ) aspect of satori, in broad strokes, is the insight that we cannot know reality at all because we are part of it. Objective knowledge of what generates our experience is beyond human reach. Satori implies abandoning the hope to discover reality. Tao involves the subsequent inversion of the metaphysical model based on realizing that we have complete knowledge of experience. We are at liberty to marvel at our experience for its own sake. We may rationally or otherwise explore its elements and patterns and share our findings.

So, the case seemed closed. I could be pleased to have found what I had been looking for. Surely, I wasnt the first to experience satori and find Tao. Besides, people growing up in the East are in a better cultural position to explain them than I. I could just continue my everyday life with an added touch of agreeable enlightenment.

However, something was still puzzling me. As an engineer, I like to understand how things work to cater to my problem-solving habit. I found it intriguing that an entirely rational fundamental insight could be glaringly absent from the Western collective consciousness. How was this possible?

Ultimately, the answer is evolution. The human susceptibility to the illusion of duality can be traced back to how evolution has shaped our minds. It follows that psychology and natural science are related topics: A better understanding of the workings of the mind improves our grasp of the physical world. Indeed, I learned that the impact of the confused conception of reality goes well beyond the personal sphere.

Next page