Contents

Foreword

by Charles Correa

The physical aspects of any city, ie its buildings, streets, public spaces etc, dont just spring into being. They are the products of a complex interplay of building materials and technology, municipal regulations, street setbacks and so forth. Most books on Bombay, intended primarily for coffee tables, fill us with nostalgic imagery but provide little or no explanation of the mechanics of that crucial interplay ie, just why in those days, our city looked the way it did.

This book is different. Kamu Iyer is an architect who has lived in Bombay all his life. He is observant, analytical, visual. He understands how people use spaces especially public spaces. And he has a sense of History.

In Iyers genealogy of this city, there are of course the usual suspects: Bombay Gothic, Indo-Saracenic, Art Deco and so forth. But there is much more: for instance, the Bombay Improvement Trust which from 1898 to 1926 was directly responsible for pioneering the new developments that made Bombay the most progressive city in India. Developments that were prime examples for the rest of urban India to follow from a number of elegantly scaled new streets like Laburnum Road and Alexandra Road in Gamdevi to the creation of whole neighborhoods, like the office area (behind the Bombay Gym) between Waudby and D N Roads, and the Parsi and Hindu housing colonies in Dadar. The Development Department, that followed the B.I.T. was also responsible for Marine Drive that brilliant urban gesture that has become the iconic image of our city.

This is what made Bombay the magnificent city it was and this process continued after Independence with the augmentation of these capabilities at state and central government levels. The future of Indias cities seemed to be in capable hands. Tragically, in the last few decades, almost all this capacity has been systematically dismantled. And why? Because it comes in the way of corrupt political agendas. So now decisive shifts in the citys development (savage increases in FSI, drastic changes in land use etc) are NOT vetted by any planning agency nor exposed to any public scrutiny but are sent directly from the cabinet to the Urban Secretary to the Municipal Commissioner for implementation.

All this has led to criminally wretched and dehumanising conditions for the have-nots in our cities. And this is why Iyer has a chapter with the laconic title: YOU CAN JUDGE A CITY BY HOW ITS POOR LIVE. That is indeed a profound thought. In his own gentle critique of our citys development, Iyer delivers a lethal punch that takes your breath away.

For we all know we have created a city that only the top 25 per cent of its inhabitants can afford. A city of high-rise towers and high-speed elevators, of flyovers and multi-level car parks a city that has no connection whatsoever with the actual prevailing income profile of its citizens. This was not the case some decades ago when Bombays growth rate was just as high but where the existing rules generated typologies that were affordable to almost all. The problem then was of overcrowding in the rooms not of whole families being forced to live out on the pavements. This is a problem that we ourselves have created, starting in the 1960s and we should get full credit for having done so.

Iyers book is like a leisurely stroll through the city sometimes in a tram or bus but most often on foot the schoolboy followed by the college student and finally the curious professional, always looking, questioning, seeking to understand. And as we witness the development of the city, we learn about the gradual metamorphosis of the new typologies that were developed here (for chawls, for apartments, for houses) and about the architects (Claude Batley, G B Mhatre and others) who helped create them.

And throughout, Iyer is like a modern-day Proust sifting through his memories and insights, presenting them for our consideration. And just like that small Parisian tea-cake more than a century ago, today the sight of a metal railing of a boundary wall recalls to his mind the memory of a schoolboy sitting on that railing, waiting for his turn to bat. It brings back another Bombay. And perhaps reading through this book will help us understand what is going wrong with our city and provide us with clues on how to reverse the grave (perhaps terminal) blunders we are currently making.

Introduction

The voyage of discovery is not in seeking new landscapes but having new eyes

- Marcel Proust

In this book I write about the built form of the city as I have seen it grow and change since the 1940s. It is written largely from my experience through my years as a student, professional architect and teacher in schools of architecture, though I have also drawn from the observations of many others, young and old. I also look at the way in which the Improvement Trust, the Bombay Development Department and the Bombay Municipal Corporation, through their interventions, altered the homes and lives of people over the decades. This book is about a changing order and the citys fabric.

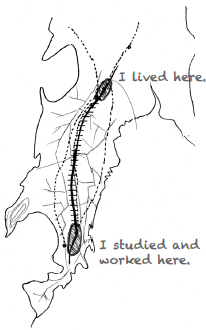

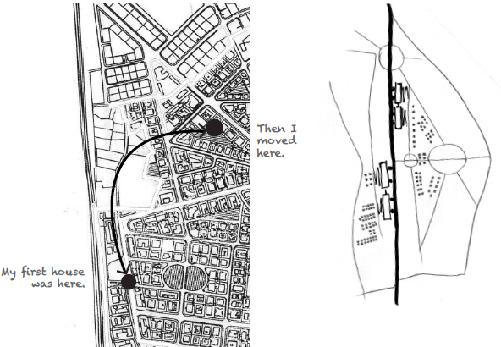

Growing Up In A Planned Neighbourhood

I have lived all my life in Dadar-Matunga in the northern part of the island city of Bombay. I spent my first nine years in Hindu Colony, after which we moved to Parsi Colony, a neighbourhood that stood just across the main road from it. As a child, I would imagine this road, Vincent Road (now called Dr Ambedkar Road), to be a thick black line on which red trams ran. Both Hindu Colony and Parsi Colony, though noticeably different from each other, were part of the Dadar-Matunga Estate Scheme V developed in the 1920s by the Bombay Improvement Trust, the main city development authority of that time. It was set up by the government to replan crowded areas of the city and develop new neighbourhoods.

I lived in a planned neighbourhood at the northern end of the island city. The train took me to school.

For a child the road was a thick black line on which red trams ran.

Hindu Colony

The precinct was made up of shaded roads, plenty of open space and three-storey buildings. Contrary to its name, Hindu Colony was not meant exclusively for Hindus although the majority of its residents were middle-class Maharashtrians. Perhaps it was so called only to distinguish it from Parsi Colony, which was reserved mostly for members of that community. Several Christians owned houses in Hindu Colony. My early friendships were with the boys of a Goan Christian family that lived down the road. We went to the same school in Dhobi Talao, travelling together by train every day. The family was headed by a stern widow. I used to wonder why a Christian lady would want to bring up her family in a Hindu locality rather than one where her own community resided. To that question my uncle surmised that she probably felt safer among strangers than her own people, especially since she was attractive and without any means. In a Hindu area, she could keep prying neighbours at bay.