Conclusion

1.Reception and Legacy of Shestovs Philosophy

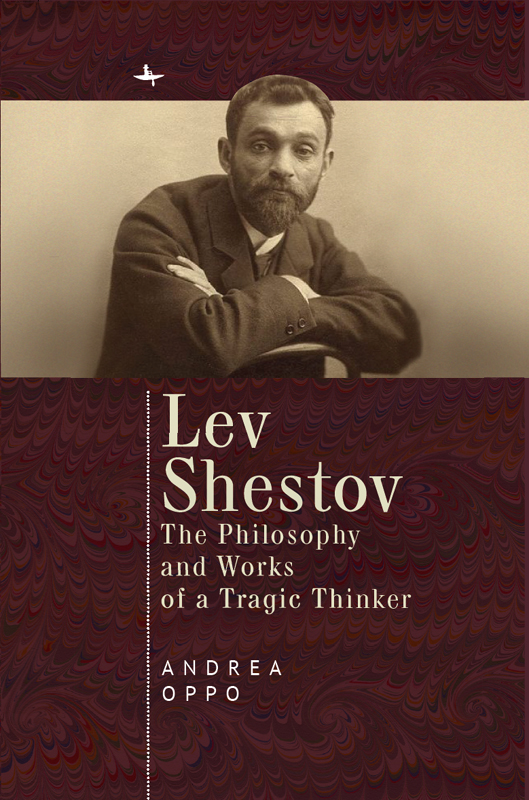

1. In the histories on Russian thought as well as in the scholarship on Russian philosophy, Lev Shestov is often labelled a dracinan unrooted, unaligned, and isolated thinker. This definition can hardly be disputed since it was Shestov who first put himself in the position of not adhering to anything: his entire thought was constructed to not follow any preestablished path and to not match any existing frame of thought. He was always very careful to not fall into this trap, that is, to not be co-opted or recruited into any official current of thought. Despite this, he was never completely isolated, but often took part in gatherings of intellectuals, and he was always surrounded by many true friends, even among the intellectuals. From the beginning of his career in Russia, he was a part of the Mir iskusstva circle, he met the rising group of the Symbolists, he went to the philosophical meetings in Ivanovs tower and attended many assemblies in various philosophical-religious societies in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Kiev. He was there, one could say, where the ideas circulated and where intellectuals discussed the most delicate themes of Russian society, and yet he often stood aside in those debates, always manifesting a critical attitude towards any of them. Ten or twenty years later, nearly the same story was repeated in Europe, where he met some of the major intellectuals of his times: Andr Gide, Jacques Rivire, Lucien Lvy-Bruhl, Andr Malraux, Jules de Gaultier, Gabriel Marcel, Jean Paulhan, Charles du Bos, Henri Bergson, as well as Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Max Scheler, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, and many others. His role in these relationships was often that of devils advocate as he never indulged in any compromise or stepped back from his uncompliant, often harsh attitude in dialoguing with others.

All the major Russian historians and scholars of the Silver Age acknowledged Shestovs unyielding and oppositional nature, which contrasted oddly with his very generous and kind attitude in his personal relations. The result, for them, was objective difficulty in placing his thought and his role within what was actually a fruitful and fecund season for Russian intellectual historya season which he was nonetheless a part of. It may come as no surprise, then, that in such a milestone of Russian religious historiography as The Ways of Russian Theology (1937), Georgii Florovskii did not mention Shestov at allnot even among the group of opponents of dogma (Vasilii Rozanov and Nikolai Minskii) in the section of the book dedicated to the Russian religious renaissance. It seems, as it were, that Shestov was too much of an idiosyncratic figure to even be raised to the rank of adversary of Florovskiis views.

By the same token, in his History of Russian Philosophy (1951) On the contrary, the point Losskii cannot absolutely accept in Shestov, the one in which he goes too far (145), is his rejection of the law of identity and contradiction, especially when it is applied to God. Yet, for Losskii, as far as the last religious truths are concerned, Shestov maintained and defended positive statements, in particular with regard to the living, creatively active individual personality (145).

Nikolai Berdyaevs seminal work The Russian Idea (The Main Problems of Russian Thought in the 19th and early 20th centuries), first published in 1946, is to be considered no less a history of Russian philosophy than Losskiis book, in that it is guided by an equal aim of tracing, or regaining, the lineage of the true path of Russian philosophical identity, albeit in this case an antinomic and a dialectical one (as is the thesis of Berdyaevs book), throughout the development of history, and also provides an overview of all Russian thinkers. Berdyaev manages, not without effort, to carve out a small place for Shestov within the destiny of the Russian idea. Although admitting that he stood apart from the main channel of Russian thought, Berdyaev acknowledges Shestov to be a piece of the multiform Russian Renaissance of the beginning of the century as an original and notable thinker [... ] who fought against the general obligations of morals and of logic (Berdyaev 1992 [C], 249). But he also criticizes

The considerations expressed by Vasilii Zen kovskii are entirely different in tone and content. In his monumental History of Russian Philosophy (19481950),that is, in taming Shestovs thought and bringing it back into more customary paths: in this case, the building or reconstruction of an original Russian religious philosophy. To obtain this, Zenkovskii must obviously minimize all the irrational aspects of Shestov, and he is actually obliged to specify more than once that what may seem too extreme or excessive in his thought is, in fact, submerged in the significance and creative depth of his basic undertaking (791).

The situation is no different as far as the specific articles dedicated to Shestov are concerned. During his Russian period, Shestov actually received considerable attention from critics and his works were always widely reviewed. This is no surprise, since his ability to write in an elegant and attractive style was always his universally praised trademark. But this gift was also a double-edged sword: as Berdyaev asserted (cf. Berdyaev 1992 [C], 250), his thoughtas opposed to his bookshas been always largely misunderstood. Many expected to find a literary critic in him but then discovered he was a philosopher, whereas, in their turn, the philosopherseven those who were potentially closer to himdid not find enough of a philosophical system in his works to make them interesting to their eyes. For this reason, perhaps, aside from the book reviews and a general appreciation of his style and of his inspirations, while he was living in Russia Shestov had only three major studies dedicated to him that sought to constructively analyze his thought as a whole and to put it in a dialogue with other writers and tendencies of his time. One study was written by Berdyaev in 1905, Tragediya i obydennost [Tragedy and the Everyday] (Berdyaev 1905 [B3]), another by Ivanov-Razumnik in 1908, O smysle zhizni [On the Meaning of Life] (Ivanov-Razumnik [B3]), and the last by Boris Griftsov in 1911, Tri myslitelya: V. Rozanov, D. Merezhkovskii, L. Shestov [Three Thinkers: V. Rozanov, D. Merezhkovskii, L. Shestov] (Griftsov [B3]).

Berdyaevwhose study has been already examined in depth in

Ivanov-Razumnik highly valued Shestovs contribution to the development of Russian intellectual history and he included Shestovs philosophy, along with the artistic work of Sologub and Andreev, within the immanent subjectivism phase of Russian thought (which he considered himself to belong to). In this regard, Ivanov-Razumnik stated that all three authorsSologub, Andreev, and Shestovcould well have said of themselves: We all came from Ivan Karamazov (Ivanov-Razumnik [B3], 5), since he identified their three world conceptions as deriving directly from Ivan Karamazovs cursed questionsthis brilliant philosopher created by Dostoevskii (4). According to Ivanov-Razumnik, due to a number of historical factors (e.g., Positivism, Marxism, Tolstoism, Aestheticism), a real answer to Ivan Karamazov arrived quite late in Russia: this happened with Nikolai Mikhailovskii, first, and then in a full way with these three authors.was just an unconscious ideologue of decadence for those who did not reach any worldview, who want to save themselves from any obligation (251).

Next page