Ancient Commentators on Aristotle

GENERAL EDITORS: Richard Sorabji, Honorary Fellow, Wolfson College, University of Oxford, and Emeritus Professor, Kings College London, UK; and Michael Griffin, Assistant Professor, Departments of Philosophy and Classics, University of British Columbia, Canada.

This prestigious series translates the extant ancient Greek philosophical commentaries on Aristotle. Written mostly between 200 and 600 AD, the works represent the classroom teaching of the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic schools in a crucial period during which pagan and Christian thought were reacting to each other. The translation in each volume is accompanied by an introduction, comprehensive commentary notes, bibliography, glossary of translated terms and a subject index. Making these key philosophical works accessible to the modern scholar, this series fills an important gap in the history of European thought.

A webpage for the Ancient Commentators Project is maintained at ancientcommentators.org.uk and readers are encouraged to consult the site for details about the series as well as for addenda and corrigenda to published volumes.

Contents

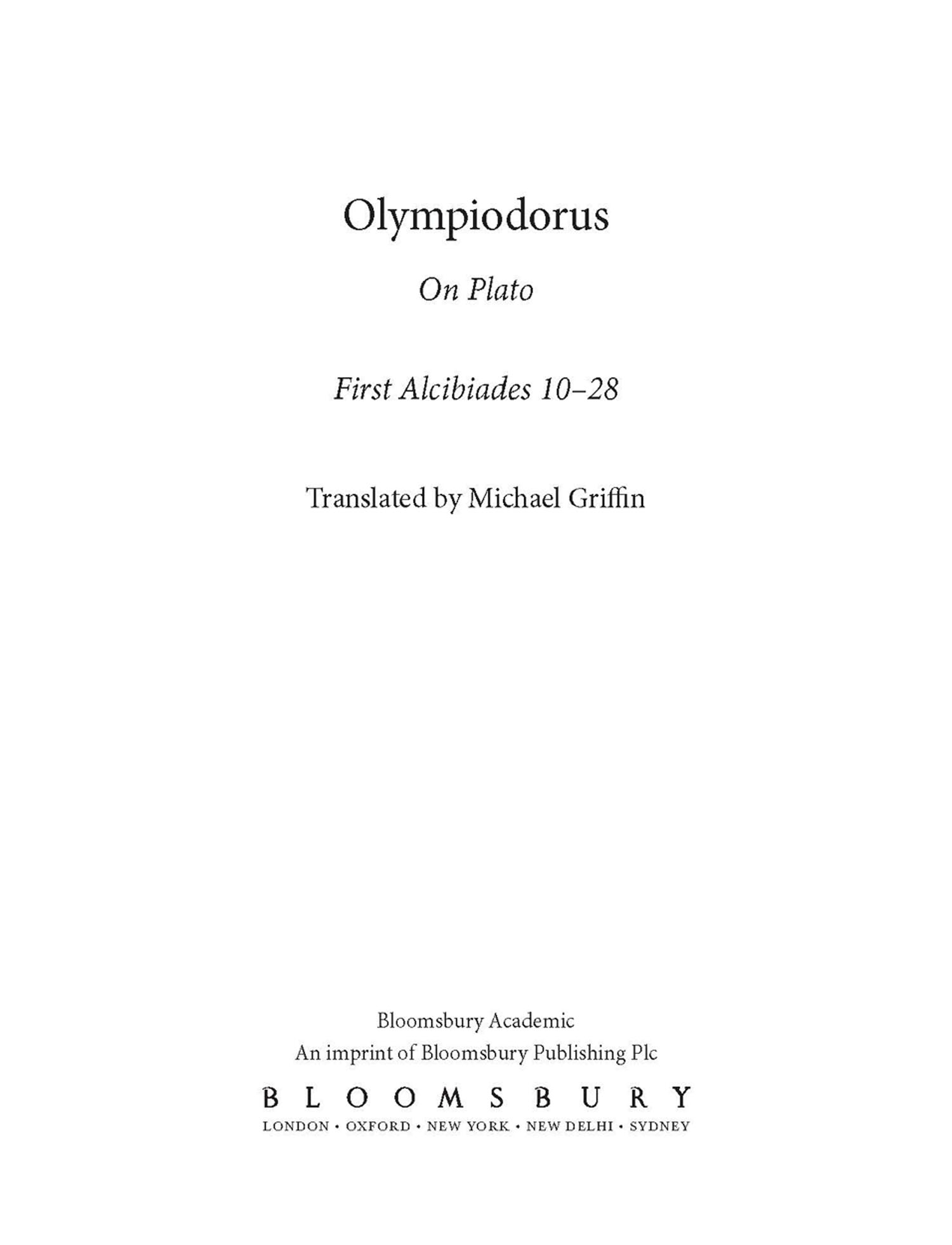

This volume completes the translation of Olympiodorus On Plato First Alcibiades, which began with the Life of Plato and Lectures 19 (Griffin 2014d). Where possible, I have attempted to maintain a fair degree of consistency across the two translations, and the Indices printed here refer to both volumes together. The Introduction printed with this volume is intended to complement, rather than duplicate, the Introduction to Lectures 19, but it can also stand alone as an introduction to Olympiodorus and the subject of these lectures.

I would like to express my particular gratitude to the funders, editors, and readers named in the Acknowledgements above, and to Richard Sorabji for consistent encouragement and constructive criticism throughout this project. I am also glad to register a special debt of gratitude to Robert B. Todd, under whose kind and patient supervision I ventured to translate my first pages of Olympiodorus during my last undergraduate year at the University of British Columbia.

The volumes remaining defects, of course, remain entirely my own responsibility.

M.J.G.

[] Square brackets enclose words or phrases that have been added to the translation for purposes of clarity.

<> Angle brackets enclose conjectures to the Greek and Latin text, i.e. additions to the transmitted text deriving from parallel sources and editorial conjecture, and transposition of words and phrases. Accompanying notes provide further details.

() Round brackets, besides being used for ordinary parentheses, contain transliterated Greek words.

Alc. = Plato(?), First Alcibiades

Anon. Prol. = L.G. Westerink, Anonymous Prolegomena to Platonic Philosophy. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co., 1962; reprinted Westbury: Prometheus Trust, 2010

DL = Diogenes Laertius

El. Theol. = E.R. Dodds, Proclus: The Elements of Theology, 2nd edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

Enn. = Plotinus, Enneads

Herm. = Hermias

in Alc. = Commentary on the Alcibiades

in Gorg. = Commentary on the Gorgias

LS = A.A. Long and D.N. Sedley, The Hellenistic Philosophers. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

LSJ = H.G. Liddell and R. Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon. 9th edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Olymp. = Olympiodorus

Plot. = Plotinus

Proleg. Log. = Olympiodorus, Prolegomena to Aristotelian Logic

Sorabji 2004 = R.R.K. Sorabji, The Philosophy of the Commentators 200600 AD. A Sourcebook. Vol. 1: Psychology (With Ethics and Religion). Vol. 2: Physics. Vol. 3: Logic and Metaphysics. London: Duckworth, 2004.

SVF = H.F.A. von Arnim, Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta. 4 vols. Stuttgart: Teubner, 1964.

For all other ancient works standard abbreviations are used.

The chapter and line number references for Olympiodorus On the Gorgias follow the edition of Westerink (1970). Those for Olympiodorus On the Phaedo follow the edition of Westerink (1976).

Olympiodorus took over Alexandrias public chair in philosophy from Ammonius (c. 435/45517/26), probably indirectly. Most of the other substantial arguments are indebted to Damascius, and Olympiodorus own voice shines through most clearly in his attempts to moderate their apparent disagreements (e.g., in Alc. 5,176,1).

Olympiodorus was, like many good teachers, a capable moderator. His lectures reveal a staunchly Hellenic professor striving to be sensitive to the faiths of a predominantly Christian That criticism arguably overlooks Olympiodorus own metaphilosophical principles about what philosophy is, and how it ought to be practised.

On Olympiodorus view, philosophy is a sort of governing craft, Olympiodorus might have considered his appearance of pliability to be symptomatic of an underlying consistency, rather than muddle-headedness.

Olympiodorus was not only a philosopher: he was also sensitive to his role as a representative of Hellenic paideia, the webwork of later ancient higher for the inspired heights of philosophy. And because he offers community courses which are virtually without prerequisites (for the sixth-century freshman from Constantinople), Olympiodorus is often obligated to translate the nested intricacies of Proclus and Damascius for a more or less uninitiated audience. The resulting introduction to Neoplatonic thought can be unusually accessible to the modern reader, compared to more technical treatises of the period.

Olympiodorus produced a wide range of lectures, a substantial number of which have survived (see Appendix for a list of works). He may have been the last professor of philosophy in Alexandria without a commitment to Christianity, at least in name. Several of his pupils, active in the later sixth and early seventh centuries, had Christian names (if the attributions to Elias and David are reliable); probably continued the schools pedagogical tradition at least into the seventh century. Copies of the schools lectures and commentaries resurface at Constantinople in the philosophical collection of the tenth century, including the single manuscript that preserved Olympiodorus Platonic lectures (Marc. gr. 196). Many would reach Italy in the fifteenth century with Basilius Bessarion to contribute to the Western renaissance of Neoplatonism.

Intuitively, each of us appears to be a singular moral agent, possessing synchronic and diachronic unity, and acting for reasons upon which we have consciously reflected: According to the later Neoplatonists who shaped Olympiodorus thought about the self, such as Proclus, we find in ourselves a moral and psychological plurality, governed by unreflective habits and appetites, and comparable to a city ruled by a mob, or a many-headed beast. For instance, Proclus describes our initial condition as follows (adopting the city-soul analogy of Plato, Republic 2, 368D369A):

[T]he multitude produces within us from our childhood defective imaginings and various affections [T]here is in each of us a certain many-headed wild beast [i.e. appetites (epithumiai) that are often contradictory], as Socrates himself has observed [Rep. 9, 588C], which is analogous to the multitude; and this is just like the people (

Next page