Publication of A Principled Stand is made possible in part by grants from the Scott and Laurie Oki Endowed Fund, which publishes books in Asian American studies, and the Capell Family Endowed Book Fund, which supports the publication of books that deepen the understanding of social justice through historical, cultural, and environmental studies.

The book also received generous support from the George and Sakaye Aratani Professorship in Japanese American Redress, Incarceration, and Community, at UCLA.

A full listing of the books in the Oki Series can be found at the back of the book.

2013 by Lane Ryo Hirabayashi

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Thomas Eykemans

Composed in Chaparral, typeface designed by Carol Twolmby

16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145, USA

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

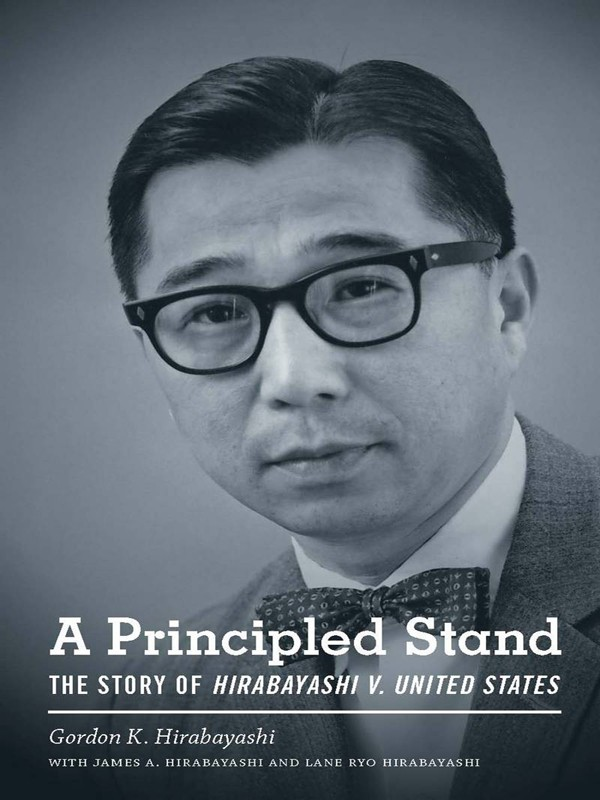

Hirabayashi, Gordon K.

A principled stand : the story of Hirabayashi v. United States / Gordon K. Hirabayashi with James A. Hirabayashi and Lane Ryo Hirabayashi.

p. cm. (Scott and Laurie Oki series in Asian American studies and Capell family book)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99270-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Hirabayashi, Gordon K.Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Japanese AmericansEvacuation and relocation, 19421945. 3. Japanese AmericansLegal status, laws, etc. 4. Japanese AmericansCivil rights. 5. United States. Constitution. 5th Amendment. I. Hirabayashi, James A. II. Hirabayashi, Lane Ryo. III. Title.

KF228.H565H57 2013 341.6'7dc23 2012038855

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

ISBN-13: 978-0-295-80464-4 (electronic)

PREFACE

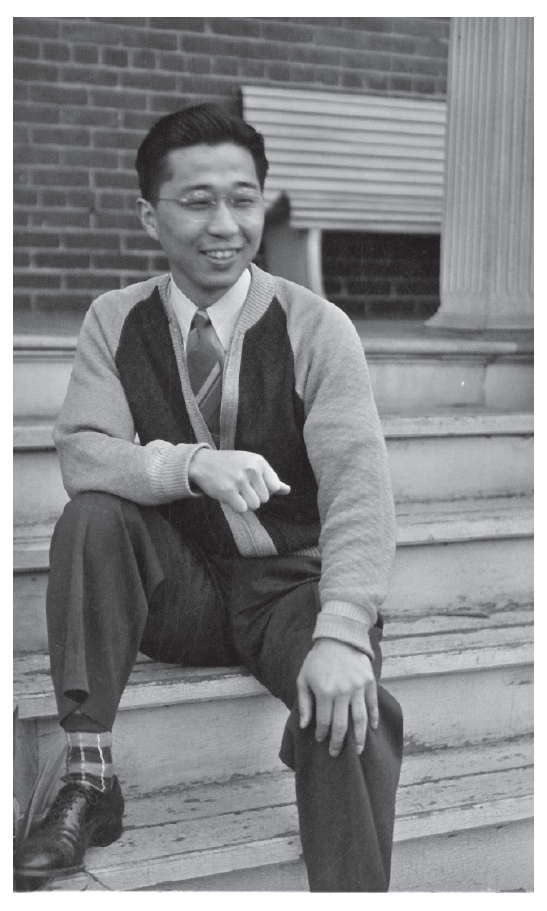

GORDON KIYOSHI HIRABAYASHI (19182012) IS BEST KNOWN for being one of three Japanese Americans whose legal challenges to the curfew imposed on and the subsequent removal of Japanese Americans from their homes reached the U.S. Supreme Court during the 1940s. We wrote A Principled Stand in order to complement the many publications that examine Gordon's court cases. While most of the available literature focuses on the legal aspects of his resistance, our focus is on Gordon as a person. We use his own words to try to convey what inspired him to challenge the federal government during World War II.

Some forty years after Gordon's initial trials, legal historian Peter Irons and a team made up mainly of young lawyers born after the war revisited Gordon's conviction by utilizing a rare doctrinewrit of error coram nobisto reopen his case. Their ultimate victory enhanced Gordon's reputation as a resister. He was not only heralded in the Japanese American community but also widely recognized by mainstream institutions for his principled stand during the 1940s.

The following three topics provide the background for reading Gordon's story: the origins of this project; Gordon's legal cases; and a note on the process of constructing his narrative in A Principled Stand.

ORIGINS OF THE PROJECT

During the 1990s, James (Jim) Hirabayashi, Gordon's younger brother, visited Gordon in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and recorded several interviews. In 2008, Jim returned to Canada and collected extensive personal files that were stored in Gordon's garage. After perusing the material, he came up with the idea of using these unpublished primary documents to convey Gordon's thoughts and emotions during the 1940s. He invited his son, Lane, to join him, and for three years they read, met, corresponded, and exchanged ideas on how best to carry out this task.

The purpose of this book is to convey what was going through Gordon's mind at the time. What inspired and enabled him to withstand the psychological and emotional burden of sustained, nonviolent resistance? How did he endure the challenges of taking on the federal government and its massive legal resources? Who gave him hope, and how? The pages that follow endeavor to give readers a sense of Gordon's background and the people, networks, and community organizations that framed his upbringing and life into his early twenties.

LEGAL CASES

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, delegating broad powers to the secretary of war and his military commanders for the purpose of protecting national security. Although Executive Order 9066 named no specific group, it gave military commanders the right to remove any potentially dangerous, or even suspicious, individuals from military areas as well as to confine such persons if necessary. Congress backed the executive order by passing Public Law 503, which subjected civilians who violated the order to imprisonment and fines.

In February 1942, authorities decided that it was necessary to remove Japanese Americans from areas that were seen as being too close to strategic coastal waters. Japanese Americans were ordered to leave Terminal Island, California, on March 14, 1942, and move to Los Angeles proper or inland, only to be removed again, to Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) camps the following month. Likewise, Japanese Americans on Bainbridge Island, Washington, were ordered to leave their homes on March 23, 1942.

On March 28, the Western Defense Command, under General John L. DeWitt, issued a proclamation that was essentially a curfew order. It confined all enemy aliensGermans, Italians, Japanese, and what the army called non-aliens of Japanese ancestryto their homes between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. and restricted travel beyond a five-mile radius from their residences.

In April 1942, the government began to post official proclamations on telephone poles and post office bulletin boards in California and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona: NOTICE: TO ALL PERSONS OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY, BOTH ALIEN AND NON-ALIEN. These notices ordered all persons of Japanese ancestry, whether or not they were U.S. citizens, to report to the Wartime Civil Control Administration. As a result, and by governmental fiat, Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and communities. Under military guard, they were first transported by buses and trains to one of sixteen temporary WCCA detention camps, euphemistically called assembly centers, most of which were in California. Horse stables and crudely built barracks served as mass housing for tens of thousands.

By the fall of 1942, after stays ranging from weeks to six months, inmates of these camps were typically removed to one of ten more permanent American-style concentration camps. Run by the newly created War Relocation Authority (WRA), these camps were located away from the coasts, in some of the most desolate parts of California, Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas.