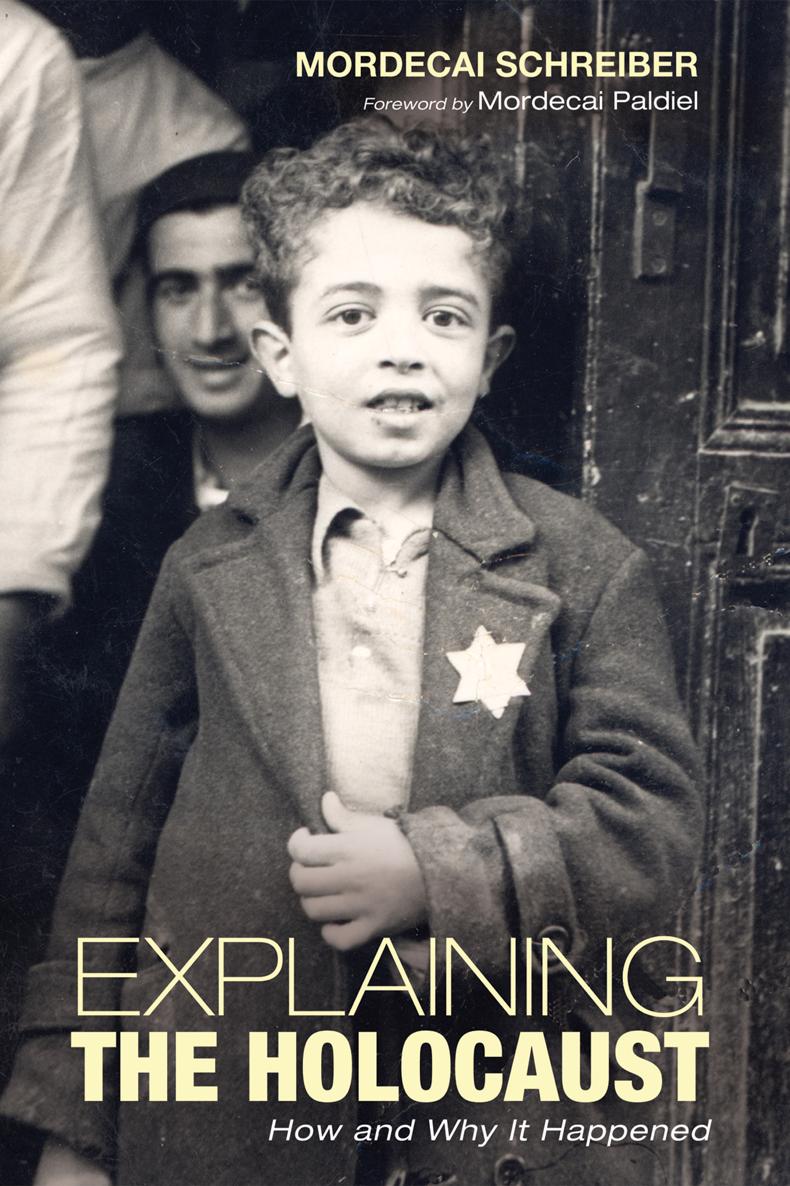

Explaining the Holocaust

How and Why It Happened

Mordecai Schreiber

Foreword by Mordecai Paldiel

EXPLAINING THE HOLOCAUST

How and Why It Happened

Copyright 2015 Mordecai Schreiber. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, W. th Ave., Suite , Eugene, OR 7401 .

Cascade Books

An Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers

W. th Ave., Suite

Eugene, OR 97401

www.wipfandstock.com

ISBN : 978-1 - 4982-1991 -

EISBN 13: 978-1-4982-1992-1

Cataloging-in-Publication data:

Schreiber, Mordecai.

Explaining the Holocaust : how and why it happened / Mordecai Schreiber ; foreword by Mordecai Paldiel.

xx + p. cmBibliographical references and illustrations.

ISBN : 9781 - 4982 1991 -

. Holocaust, Jewish ( 1939 1945 ).. HolocaustJewish ( 1939 1945 )Causes.. Holocaust, Jewish ( 1939 )Religious aspectsJudaism.. Holocaust, Jewish ( 1939 1945 )Religious aspectsChristianity.. Righteous Gentiles in the Holocaust. I. Paldiel, Mordecai. II. Title.

D. S 2015

Manufactured in the U.S.A. 03/17/2015

Cover photo courtesy of Rhodes Jewish Historical Foundation

This book is dedicated to the little boy in the photo on the cover of this book. His name is Haim Angel. I first saw this photo over twenty years ago in the tiny Holocaust museum in the back of the synagogue on the island of Rhodes, and it has haunted me ever since. The boy is posing with the yellow star as a symbol of pride. In 1943 , as the Germans were losing the war, they deported him to Auschwitz, where he perished along with hundreds of members of the small centuries-old Jewish community of the island.

When in the shadow of gallows our children were crying The worlds rage had turned to silence.For You have chosen us from among all nations,You loved us, You called us beloved.For You have chosen us from among all nations,Norwegians, and Czech, and British,And as our children were marched to the gallows,Jewish children, wise children,They knew their blood didnt count in this world,They only told their mother: Kuk nisht , dont look.And as the hatchet consumed by day and by night,The Holy Father in Rome Did not go out with the Redeemers sign To witness the pogrom.To stand only once, one single day,In the place where for years, Like a lamb,Stands an unknown little boy, A Jew.

(From From among All the Nations by Natan Alterman, translated from the Hebrew by Mordecai Schreiber.)

Foreword

O ne morning in 1953 I was sitting in a yeshiva (Talmudic academy) classroom, listening to the teacher, an elderly man with a long white beard, expound a difficult Talmudic discussion. As I lost track of the hair-splitting opinions of the different rabbinic scholars, I furtively opened a book on Polish Jewry that was tucked in my table drawer and that I had borrowed from the public library. Quickly flipping through the pages, I stopped to read that in the summer months of 1942 , some two hundred fifty thousand Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto were delivered to the gas chambers in the Treblinka camp, and their remains turned into ashes. I remember sitting on my chair dumbfounded at this horrific event that took place quite recently, only eleven years ago, and that there was no mention at all and no reference to this ghastly deed in the yeshiva courses that I was attending. I wondered why this silence? Why this total educational neglect in a very traditional Jewish school? I also kept thinking what relevance the ancient Talmudic text has to that more recent catastrophe? Back at home, the story of that terrible churban (devastation)the term Holocaust had not yet come into voguewas also not discussed, though it was confirmed to have happened; this omission was also experienced by my cousin in Israel, the author of this book.

This deliberate unwillingness to deal with the most shattering event in Jewish history, an event that almost succeeded in obliterating the Jewish people or its most creative part, kept nagging in the back of my mind, and when many years later the Jewish community finally awoke from this long slumber, we all realized we had a tremendous problem on our hands of how to make sense of that watershed event. Laymen and scholars tried to advance answers from their respective disciplines to a host of questions: How was it possible for it to happen? Why did it happen? How did the Jewish community and the civilized world respond to it, and what are the lessons for the future? All the explanations advanced, and the library is full of them, fall short of providing satisfactory answers to these disturbing questions. But try we must, for once an event of this magnitude happens, defying all imagination and boggling the mind, it can happen again, and we must remain vigilant for signs of such a recurrence. Yet the more I have immersed myself in studying and understanding the Holocaust over several decades of working as an employee of Yad Vashem, and currently in teaching this subject, the more I am resigned to the thought that we will never arrive at a full explanation of how such a horrific event took place on a continent and amid people steeped in the longest tradition of civilized life and religious teachings. We will always remain at a loss, but try we must.

In 1976 , while in Philadelphia, I attended a public lecture by Professors Franklin Littell and Yehuda Bauer on the Holocaust, and suddenly something inside me burst forth, and a longtime subconscious urge to come to grips with the Holocaust took hold of me. When I further learned that Littell was giving a post-graduate course on the Holocaust at Temple University in Philadelphia, I decided to stay put and resume my studies on a post-graduate level, with an emphasis on the Shoah. I had earlier graduated from the Hebrew University with a BA degree in economics and political science and had forsaken further studies in these two important subjects. After graduating from Temple in 1982 with a PhD degree in Holocaust Studies, I returned to Israel and was appointed by Yad Vashem to head a department I had never heard about before: the Righteous among the Nations. It dealt with non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews from the Nazis. For the next twenty-four years, I was immersed in that uplifting and inspiring work, and was instrumental in adding thousands of names to this unique honor roll presented by the Jewish people and by the State of Israel (Yad Vashem having been established by legislation as a government institution). I was also able to rediscover the French Catholic cleric Father Simon Gallay, who had helped my family to cross over into Switzerland, in September 1943 , and he too was honored by Yad Vashem. At the same time, in my thinking and lectures, I tried to keep a balance between the inspiring behavior of the Righteous and the horrific deeds of the perpetrators and the nonchalant attitude of the bystanders, and I am still puzzled and perplexed, and still struggling to find the correct and proper balance between these two extreme types of behavior. Hence, my personal attempt at explaining and interpreting the Shoah is to be taken with some caution.

To properly gauge the nature of the Nazi movement and its leader, Adolf Hitler, one cannot simply regard it as an extreme form of fascism, or the display of brute force for its own sake, with total disregard for those who were not part of the Aryan community. And as far as the Jews are concerned, one cannot look upon it as just the most extreme manifestation of old-time anti-Semitism, of plain and simple hatred of Jews leading to the attempt to remove them from the face of the globe, if that could be possible. It was in truth more than that.